If you ask a random person on the street who first invented the printing press, they’ll probably bark out "Johannes Gutenberg" before you even finish the sentence. It’s the standard answer. It’s what we learned in third grade. But history is rarely that clean, and honestly, the "who" depends entirely on how you define "printing" and "press."

Gutenberg didn't just wake up in 1450s Germany and conjure the idea of transferring ink to paper out of thin air. He was a goldsmith. He was a businessman. He was a man who saw a dozen different existing technologies and figured out how to smash them together into something that actually worked for a mass market.

But he wasn't the first. Not by a long shot.

The Chinese and Korean roots we usually ignore

Centuries before Gutenberg was even a glimmer in his parents' eyes, artisans in East Asia were already mass-producing text. We're talking hundreds of years earlier. Around 600 AD, during the Tang Dynasty, Chinese printers were using woodblock printing. They’d carve an entire page of text into a block of wood, ink it, and press paper onto it.

It worked. It was effective. It’s how the Diamond Sutra was created in 868 AD, which is the oldest dated printed book we have.

Then came Bi Sheng.

Around 1040, this Chinese inventor decided that carving an entire block for every page was a massive waste of time. He created movable type. He used baked clay. Each character was a separate piece. You could rearrange them, print, then break the set and build a new page. If you're looking for the literal answer to who first invented the printing press technology of movable type, Bi Sheng is your guy.

But clay is fragile. It breaks. It doesn't hold ink well.

✨ Don't miss: Uncle Bob Clean Architecture: Why Your Project Is Probably a Mess (And How to Fix It)

By the 1200s and 1300s, Korean inventors took it a step further. They started using metal. The Jikji, a Korean Buddhist document printed in 1377, used movable metal type nearly 80 years before Gutenberg's Bible ever hit the scene. This is a crucial distinction that most Western textbooks just sort of gloss over because it doesn't fit the neat European narrative.

What Gutenberg actually did in Mainz

So, if the East had metal movable type in the 1300s, why does Gutenberg get all the credit?

Context.

Gutenberg lived in a society that used the Latin alphabet. There are only 26 letters. In China or Korea, you’re dealing with thousands of different characters. Movable type is a logistical nightmare when you need 5,000 different unique molds just to write a basic essay. In Europe, you only need a couple dozen.

Gutenberg's genius wasn't just the "press." It was the system.

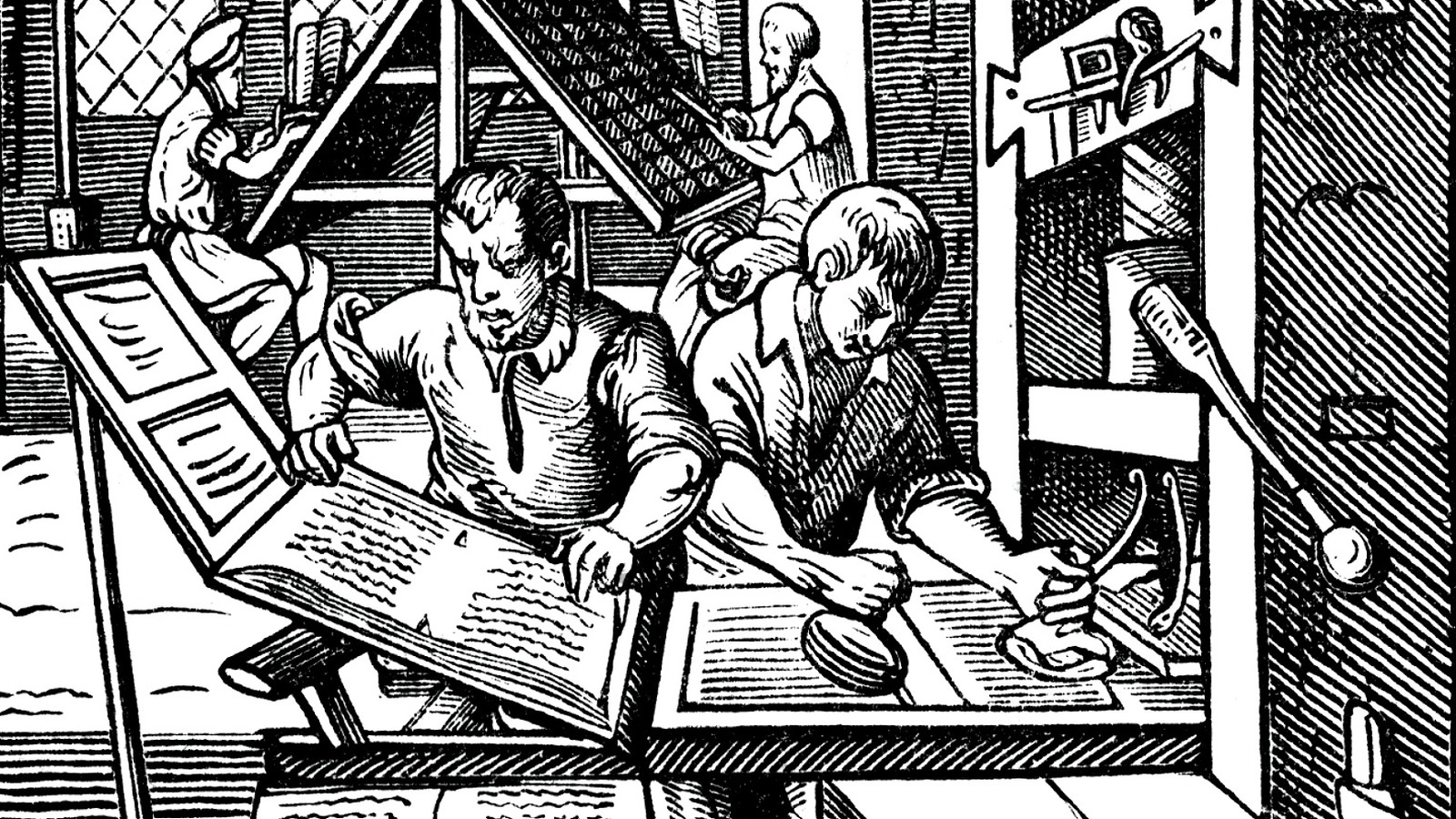

He developed a specific lead-based alloy that melted at low temperatures but cooled quickly and stayed hard. This allowed for "type-founding"—mass-producing the little metal letters themselves. He also adapted a wine press (the kind used to crush grapes) to apply even, flat pressure.

He also created an oil-based ink. Traditional Chinese inks were water-based; they worked great on rice paper with hand-rubbing, but they’d smudge or bead up on the metal type and heavy parchment used in Europe. Gutenberg's ink stuck to the metal and transferred cleanly.

🔗 Read more: Lake House Computer Password: Why Your Vacation Rental Security is Probably Broken

The investor drama you didn't hear about

History likes to paint inventors as lone geniuses working in garages. Gutenberg was more like a desperate startup founder. He was broke.

He took a massive loan from a guy named Johann Fust. When Gutenberg was finally close to finishing his famous 42-line Bible, Fust sued him. He took the equipment. He took the shop. Gutenberg was essentially kicked out of his own revolution right as it was succeeding. Fust and Gutenberg’s assistant, Peter Schöffer, ended up reaping a lot of the initial glory and profit.

It’s a classic story of the tech guy getting screwed by the VC.

Why the printing press changed everything (fast)

Before this, books were for the elite. If you wanted a Bible, a monk had to sit in a room for a year and hand-copy it. It cost as much as a house.

Suddenly, you could pump out 180 copies in the time it took to write one.

This created a feedback loop. Because books were cheap, people wanted to learn to read. Because more people could read, there was more demand for books. It wasn't just about religion, either. It was about science. It was about dissent.

Without the printing press, the Protestant Reformation probably stays a local argument in Germany. Instead, Martin Luther’s ideas were printed and spread across Europe faster than the Catholic Church could burn them. The "viral" tweet of the 1500s was a broadsheet printed on a hand-operated press.

💡 You might also like: How to Access Hotspot on iPhone: What Most People Get Wrong

The spread of the tech

- 1450s: Mainz, Germany (The epicenter).

- 1460s: The tech leaks. It moves to Italy.

- 1470s: William Caxton brings it to England.

- 1500: There are over 200 printing centers in Europe.

By the turn of the century, we’re talking millions of books in circulation. This is the "Information Age" 1.0. It's the moment human knowledge stopped being something that stayed in one person's head or one specific library and became something that could be "backed up" in a thousand different locations.

The "First" debate: A nuance check

When we ask who first invented the printing press, we are usually asking three different things at once.

If you mean "who first thought of movable type," the answer is Bi Sheng.

If you mean "who first used metal movable type," the answer is anonymous Korean printers (with the Jikji as proof).

If you mean "who created the mechanical press system that triggered the modern world," the answer is Gutenberg.

It's okay to acknowledge all three. In fact, you have to. If you don't, you're missing the reality of how technology actually evolves. It's never one "Aha!" moment. It's a slow burn of different cultures solving similar problems until someone hits the right economic and linguistic conditions to make it explode.

How to trace the history yourself

If you're a history nerd and want to see this stuff in the flesh, you don't just have to take a textbook's word for it.

- Check out the Jikji: The National Library of France holds the only surviving copy of the second volume. It’s the smoking gun for Korean metal type.

- Visit the Gutenberg Museum: It’s in Mainz, Germany. They have reconstructions of his original press. Seeing how heavy those metal plates are changes your perspective on how "automated" this actually was. It was back-breaking manual labor.

- Look at Incunabula: This is the term for books printed before 1501. Many university libraries have them. If you look closely at the letters, you can see the slight indentations where the metal type bit into the paper—the "kiss" of the press.

The printing press didn't just give us books. It gave us the concept of "the public." It gave us the ability to argue with people we'd never met. It's the direct ancestor of the screen you're reading this on right now.

Next Steps for Research

To get a deeper look at the transition from manuscript to print, look into the work of Elizabeth Eisenstein. Her book, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change, is basically the Bible for understanding how this one machine flipped the world upside down. You should also look up the "Diamond Sutra" in the British Library's digital collection to see what printing looked like centuries before Europe caught up.