The year 1968 was, quite frankly, a total mess. If you think modern politics is divisive, 1968 would like a word. Between the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, and riots in the streets of Chicago, the American psyche was essentially held together by duct tape. People often ask, who did Nixon run against in 1968, thinking it was a simple two-man race. It wasn’t. It was a three-way collision that featured a sitting Vice President, a former Vice President, and a firebrand segregationist who threw a massive wrench into the Electoral College.

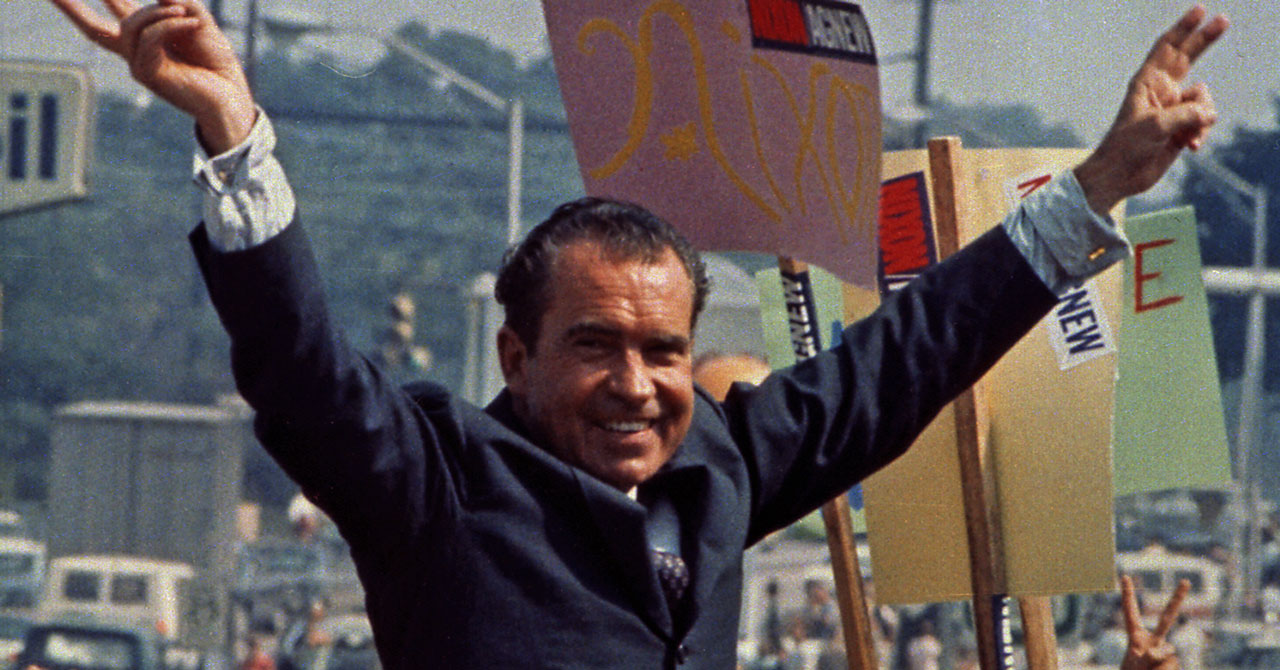

Richard Nixon didn't just walk into the White House. He navigated a minefield.

The Democratic Collapse: Hubert Humphrey’s Impossible Task

Hubert Humphrey was the guy left holding the bag. As Lyndon B. Johnson’s Vice President, he was tethered to a war that half the country hated and the other half thought we weren't winning fast enough. Humphrey was a "Happy Warrior," a man of genuine civil rights conviction, but by the time he secured the nomination at the disastrous Democratic National Convention in Chicago, he looked like the face of the establishment.

The convention was a nightmare. While Humphrey was being nominated inside, police were clashing with anti-war protesters outside in what was later described as a "police riot." This imagery killed his momentum before he even started. He didn't win a single primary. Think about that. In 1968, the system allowed him to take the nomination through party bosses and delegates without ever facing the voters in a primary booth. It drove the youth vote absolutely insane.

🔗 Read more: 2024 Popular Vote Map: What Really Happened Behind the Red Shift

Humphrey's biggest hurdle wasn't even Nixon at first; it was his own boss. LBJ wouldn't let him break away on Vietnam policy until the very end of October. By then, it was almost too late.

The Wildcard: George Wallace and the American Independent Party

You can't talk about who did Nixon run against in 1968 without talking about George Wallace. He was the former Governor of Alabama, famous for his "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever" speech. Running as a third-party candidate under the American Independent Party, Wallace wasn't some fringe loser. He was a legitimate threat.

Wallace went after the "white backlash" vote. He targeted blue-collar workers in the North and traditional Democrats in the South who felt the civil rights movement had gone too far. He was populist, he was angry, and he was loud. His goal wasn't necessarily to win the presidency outright—he knew that was a long shot. He wanted to prevent either Nixon or Humphrey from getting a majority in the Electoral College. If he could do that, he could force the election into the House of Representatives and act as a kingmaker.

He ended up winning five states. Five! That’s 46 electoral votes. In a close race, that’s enough to hold the entire country hostage.

Nixon’s "Southern Strategy" and the Silent Majority

Nixon was the ultimate comeback kid. After losing to JFK in 1960 and failing to become Governor of California in 1962, everyone thought he was politically dead. But he spent the mid-60s traveling the country, building favors with local GOP leaders, and rebranding himself as the "New Nixon."

His strategy was twofold. First, he appealed to the "Silent Majority"—the people who weren't protesting, weren't dropping acid, and weren't burning draft cards. He promised "Law and Order." It was a simple message that resonated with a middle class terrified by the nightly news footage of burning cities.

Second, he implemented what we now call the Southern Strategy. He knew he couldn't out-segregationist George Wallace, but he could signal to Southern voters that a Republican administration would be much more "hands-off" regarding federal enforcement of integration. He spoke about "states' rights" and "neighborhood schools," which were essentially coded signals.

The Turning Point: The Chennault Affair

This is where things get murky and, honestly, a bit dark. For years, there were rumors that Nixon’s campaign actively sabotaged the Vietnam peace talks in Paris just days before the election. This is known as the Chennault Affair, named after Anna Chennault, a prominent Republican fundraiser.

👉 See also: The Catholic University of America: What the Brochure Won't Tell You About D.C.’s Quiet Powerhouse

LBJ had announced a bombing halt in late October, which caused Humphrey’s poll numbers to skyrocket. Humphrey was suddenly catching up. However, the South Vietnamese government suddenly backed out of the talks. Declassified tapes later suggested that Nixon's camp used Chennault to tell the South Vietnamese to "hold on" because they’d get a better deal under a Nixon presidency.

If those talks had moved forward, Humphrey likely would have won. Instead, the momentum stalled, and Nixon squeezed through.

The Final Numbers: A Razor-Thin Margin

When the dust settled, the popular vote was incredibly close. Nixon took 43.4%, Humphrey took 42.7%, and Wallace took 13.5%.

Nixon won by less than a percentage point in the popular vote, but the Electoral College map told a different story. Nixon finished with 301 votes to Humphrey’s 191. Wallace’s 46 votes didn't trigger the constitutional crisis he wanted, but they proved that a significant portion of the country was deeply alienated from both major parties.

Why Does This Matter Now?

Looking back at who did Nixon run against in 1968 provides a blueprint for how modern American politics fractured. This was the moment the "Solid South" flipped from Democrat to Republican. It was the moment the Democratic Party realized it had to change its primary system (leading to the McGovern-Fraser Commission). It was also the birth of the modern "culture war."

✨ Don't miss: Kandahar Air Base: What Really Happened to the Gate to Southern Afghanistan

The 1968 election wasn't just a political contest; it was a national nervous breakdown. Nixon won because he promised a return to normalcy, even if his own presidency would eventually end in a way that was anything but normal.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs and Voters

If you want to truly understand the mechanics of how Nixon beat Humphrey and Wallace, you should look into these specific areas:

- Study the 1968 DNC riots: Watch the documentary Chicago 10 or read Frank Kusch’s Battleground Chicago to see how the chaos directly fueled Nixon’s "Law and Order" campaign.

- Analyze the Electoral Map: Notice how the Deep South went for Wallace. This was the last time a third-party candidate won multiple states, and it explains why both parties are now so terrified of "spoiler" candidates.

- Research the "October Surprise": Look into the LBJ library's released tapes regarding the Vietnam peace talks. It’s a masterclass in how foreign policy is often used as a domestic political tool.

- Compare the "Silent Majority" to modern rhetoric: You’ll find that the language used by Nixon in 1968 is almost identical to the populist rhetoric used in the 2016 and 2024 election cycles. History doesn't repeat, but it definitely rhymes.

The 1968 election proves that in American politics, the "third man" in the race often defines the outcome as much as the two frontrunners. Whether it’s Wallace in '68 or Perot in '92, the presence of a wildcard usually signals a deeper rot in the two-party system that voters are desperate to address.