If you ask ten different engineers who created the first computer, you’ll likely walk away with five different names and a headache. It's messy. People want a clean "Alexander Graham Bell" moment where one guy shouts into a tube and changes the world, but computing didn't happen like that. It was more of a slow, agonizing crawl through gears, vacuum tubes, and punch cards.

Honestly, the "first" computer depends entirely on how you define the word. Are we talking about a pile of brass gears from the 1800s? Or a room-sized behemoth that helped end World War II?

Most school textbooks point to the ENIAC. Others swear by Charles Babbage. If you’re a purist, you might even look at the Antikythera mechanism from ancient Greece, which is basically a 2,000-year-old analog calendar. But let's be real—when you search for who created the first computer, you’re looking for the birth of the digital age.

The Victorian Visionary: Charles Babbage

Let’s start in the 1830s. Charles Babbage, a brilliant and notoriously grumpy English mathematician, got tired of human "computers" (yes, that was a job title) making mistakes in math tables. He designed the Difference Engine, a massive mechanical calculator.

👉 See also: Why an Example Ticket Coding Interview Is the New Gold Standard for Hiring

But his real masterpiece was the Analytical Engine.

This thing was wild. It wasn't just a calculator; it had a central processing unit (the "mill"), memory (the "store"), and even used punch cards for input. Sounds familiar, right? That’s exactly how modern computers work. The problem? He never actually finished it. It was too expensive, too complex, and the British government eventually pulled the plug on his funding.

We can't talk about Babbage without mentioning Ada Lovelace. While Babbage built the hardware in his head, Lovelace wrote the first algorithm intended for a machine. She saw something Babbage didn't: the potential for computers to do more than just crunch numbers. She thought they could create music or art. She was a century ahead of her time.

The World War II Turning Point

Fast forward to the 1940s. War has a way of making people invent things really, really fast. This is where the debate over who created the first computer gets heated.

In Germany, Konrad Zuse built the Z3 in 1941. It was the first working, programmable, fully automatic digital computer. It used telephone relays instead of vacuum tubes. Because he was working in isolation in Nazi Germany, his work didn't influence the UK or US much at the time. Most of his machines were destroyed in Allied bombings anyway, which is a massive historical "what if."

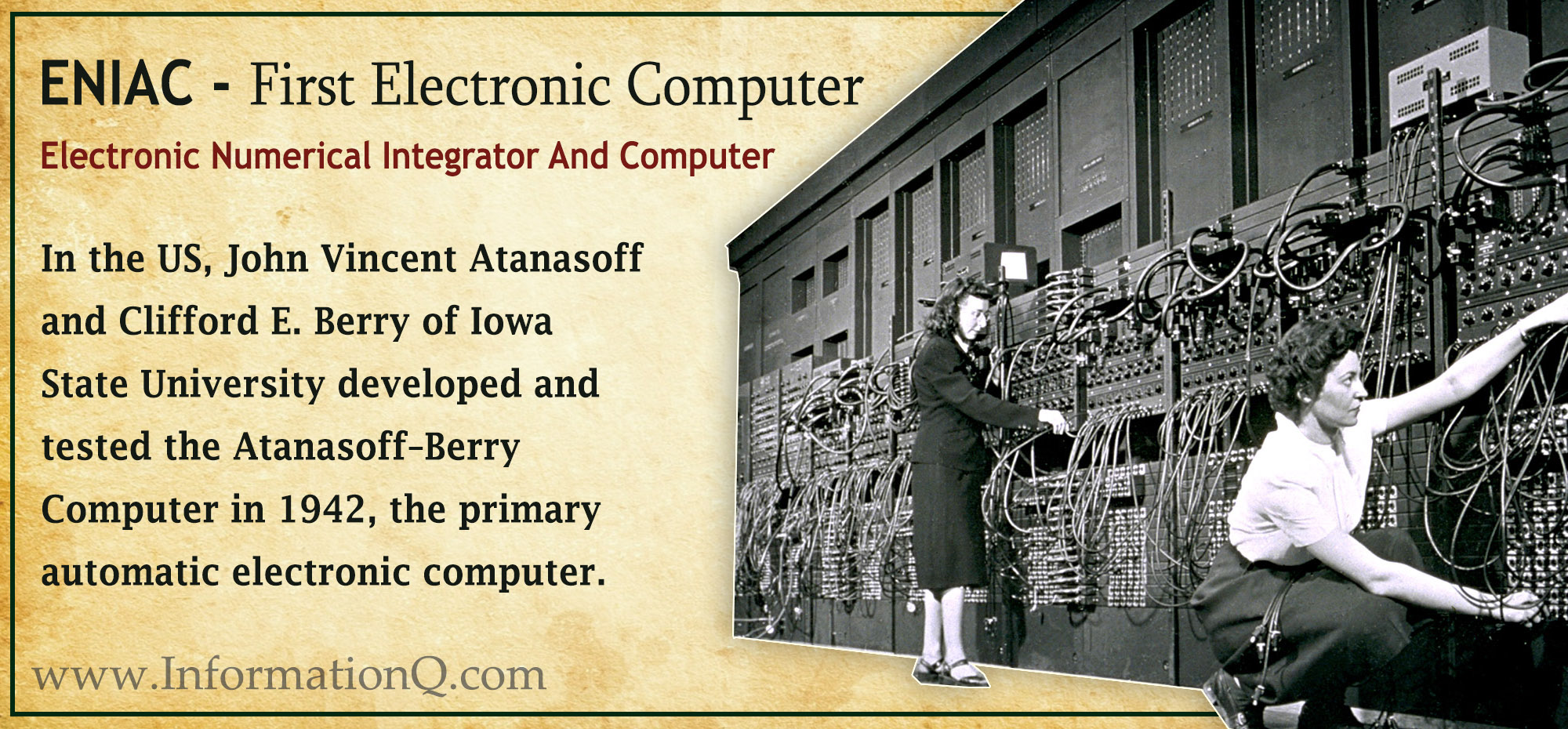

Meanwhile, across the pond at Iowa State University, John Atanasoff and Clifford Berry were building the ABC (Atanasoff-Berry Computer). It was the first to use vacuum tubes and binary math. It wasn't "Turing-complete," meaning it couldn't be reprogrammed for any task, but it was a massive leap forward.

The Colossus and the Codebreakers

Then there’s Bletchley Park. To crack the Nazi "Lorenz" cipher, Tommy Flowers designed the Colossus in 1943. It was a monster of a machine. It used 1,500 vacuum tubes and was arguably the first electronic, programmable digital computer.

But here’s the kicker: it was a state secret.

For decades, nobody knew Colossus existed. Because the British government kept it classified until the 1970s, it didn't get the credit it deserved in the early history books. Alan Turing gets a lot of the spotlight here—and rightfully so for his theoretical work on the "Universal Turing Machine"—but Tommy Flowers was the guy who actually got his hands dirty building the hardware.

The ENIAC: The One Everyone Remembers

In 1945, the ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) was unveiled at the University of Pennsylvania. Created by John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert, this is the machine most people think of as the "first" real computer.

It was huge. It weighed 30 tons and took up 1,800 square feet. It used 18,000 vacuum tubes, which blew out constantly. Legend has it that whenever they turned it on, the lights in Philadelphia dimmed.

Unlike the Z3 or the ABC, the ENIAC was a celebrity. It could calculate a trajectory in 30 seconds that would take a human 20 hours. It was the first "general purpose" electronic computer, meaning you could program it to do almost anything. Well, "programming" back then meant physically flipping switches and re-plugging massive cables.

A group of six women—Kay McNulty, Betty Jennings, Marlyn Wescoff, Ruth Lichterman, Elizabeth Bilas, and Jean Bartik—were the actual programmers. For years, they were cropped out of the photos or dismissed as "refrigerator ladies" (models posing with the machine), but they were the ones who actually made the ENIAC work.

The Legal Battle Over the Title

You’d think history would just pick a winner and move on. Nope. In the 1970s, a massive patent lawsuit (Honeywell v. Sperry Rand) actually went to court to decide who created the first computer.

The judge eventually invalidated Mauchly and Eckert’s patent for the ENIAC. Why? Because he ruled that they had derived many of their ideas from John Atanasoff and his ABC machine. Legally speaking, Atanasoff became the official inventor of the automatic electronic digital computer.

But in the court of public opinion? It’s still a toss-up.

Why it matters who we credit

Naming a single "inventor" is convenient, but it hides the truth of how technology evolves. Babbage had the logic. Zuse had the first working model. Atanasoff had the vacuum tubes. Mauchly and Eckert had the scale and the publicity.

If you're looking for a definitive answer to who created the first computer, you have to pick your "first":

- First Mechanical Idea: Charles Babbage (1837)

- First Functional Programmable Machine: Konrad Zuse (1941)

- First Electronic Digital Machine: John Atanasoff (1942)

- First Large-Scale General Purpose Computer: Mauchly and Eckert (1945)

How to explore this history yourself

If you actually want to see these beasts in person, don't just read about them. History is better when it's made of metal and wires.

- Visit the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. They have a working reconstruction of Babbage’s Difference Engine No. 2. Seeing it move is mesmerizing.

- Check out Bletchley Park in the UK. You can see a rebuilt Colossus and realize just how loud and hot those early machines were.

- Read "The Innovators" by Walter Isaacson. It’s probably the best deep dive into how all these people—from Lovelace to the ENIAC six—collaborated and competed.

The "first computer" wasn't a single "Eureka!" moment. It was a century-long relay race. We're just the ones lucky enough to carry the baton today.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

To truly understand the evolution of computing, your next move should be investigating the transition from vacuum tubes to transistors. This shift in the late 1940s at Bell Labs is what allowed computers to move from room-sized giants to the device currently in your pocket. Research the work of William Shockley, John Bardeen, and Walter Brattain to see how the "first" computers became "modern" computers.