Ever wonder why we can see a virus? Not just a fuzzy blob, but the actual structural spikes of a coronavirus or the geometric perfection of a bacteriophage. It’s because of a machine that, frankly, shouldn't have worked according to the physics of the late 1800s. If you’ve ever Googled who created the electron microscope, you probably saw a single name pop up in a snippet. Maybe Ernst Ruska. Maybe Max Knoll. But history is rarely that tidy. It was actually a desperate race in a gray, pre-war Berlin lab that felt more like an engineering workshop than a temple of high science.

Light has limits. That’s the core of the problem. By the 1920s, scientists hit a wall called the Abbe Diffraction Limit. Basically, if an object is smaller than the wavelength of light, you can't see it. It doesn't matter how expensive your glass lenses are; the physics says "no." To see the truly tiny, we needed a shorter wavelength. Electrons were the answer. But how do you "focus" a beam of particles like you focus a beam of light?

The Berlin Breakthrough of 1931

The story really starts at the Technical University of Berlin. Ernst Ruska was a young graduate student, and his supervisor was Max Knoll. They weren't actually trying to build a world-class microscope at first. They were messing around with cathode-ray oscilloscopes. In 1931, they realized something huge: magnetic coils could act like lenses for electrons.

It sounds simple now. It wasn't then.

They built a crude prototype. It didn't even "see" things better than a cheap toy microscope you'd buy at a hobby shop. In fact, its magnification was a measly 17x. But it proved the concept. By 1933, Ruska had built a version that finally surpassed the resolution of traditional light microscopes. This was the moment the door swung open. We weren't just looking at cells anymore; we were looking at the atoms of life.

💡 You might also like: Tech Deals Today: Why You Should Probably Skip the Hype and Wait for Spring

There's a bit of a misconception that Ruska did this all alone in a vacuum. He didn't. While he and Knoll were tinkering in Berlin, a guy named Reinhold Rudenberg was also filing patents for an electron microscope. Rudenberg was the scientific director at Siemens. There’s been a lot of academic bickering over the decades about who actually "invented" it first. Rudenberg’s supporters say his patents prove he had the idea down on paper before Ruska had a working model. But in the world of science, usually, the person who makes the thing work gets the glory.

Why the Nobel Prize Took 55 Years

Here is something that kinda blows my mind. Ernst Ruska didn't get the Nobel Prize for his work until 1986. That is a fifty-five-year wait. Usually, if you revolutionize science, they give you the medal while you've still got some hair left.

Why the delay? Honestly, the Nobel Committee is notoriously slow, but there was also the "competition" from the Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) and other variations. The committee finally recognized that without Ruska’s initial Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM), none of the other stuff happens. By the time he won, he was 79 years old. Max Knoll had already passed away by then, which is why he isn't officially on the Nobel roster for the invention.

It Wasn't Just One Invention

When we talk about who created the electron microscope, we have to acknowledge that the machine you see in a modern university lab today isn't just Ruska's design. It’s a Frankenstein’s monster of different breakthroughs.

- Bodo von Borries: He was Ruska's brother-in-law and a massive part of the early research. He helped turn the prototype into a commercial reality at Siemens.

- Ladislaus Marton: Working in Belgium, he took the first electron micrographs of biological samples. Before him, people thought the electron beam would just fry any biological tissue instantly. He proved you could actually look at life without it turning to ash immediately—sorta.

- Manfred von Ardenne: He’s the guy who pioneered the Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) in 1937. While Ruska’s version shot electrons through a sample, Ardenne’s version bounced them off the surface. This gave us those incredible 3D-looking images of insects' eyes and pollen grains we all saw in science textbooks.

The Siemens Connection and the War

By the late 1930s, the invention moved from the lab to the factory. Siemens & Halske (the giant German engineering firm) saw the potential. They put Ruska and von Borries on the payroll. In 1939, they released the first commercial electron microscope.

Then World War II hit.

The development of the microscope became tangled in the war effort. While the Germans had a head start, researchers in the US and the UK weren't just sitting around. At the University of Toronto, Eli Franklin Burton and his students, James Hillier and Albert Prebus, built the first high-resolution electron microscope in North America in 1938. Hillier later went to RCA (Radio Corporation of America) and turned it into a massive commercial success in the States.

It’s easy to look back and see a straight line of progress. It wasn't a straight line. It was a chaotic mess of patents, war-time secrecy, and different labs across the globe trying to outdo each other.

The Reality of Using One Today

If you ever get the chance to stand in a room with a modern TEM, do it. It’s intimidating. You’re looking at a giant metal column that has to be kept in a near-perfect vacuum. If a single molecule of air gets in the way of that electron beam, the whole image is ruined.

Scientists today use these machines to map the "connectome" of the brain—basically a wiring diagram of every neuron. We’re talking about resolution at the picometer scale. 180,000x magnification is standard. Some can go much higher. We have moved from seeing "blobs" to seeing the actual arrangement of atoms in a crystal lattice.

What Most People Get Wrong

People often think the electron microscope is just a "stronger" version of a regular microscope. It’s not. It’s fundamentally different technology.

A light microscope uses photons. An electron microscope uses—obviously—electrons. But because electrons are charged particles, you can't use glass to bend them. You have to use "electromagnetic lenses." These are basically copper wire coils that create a magnetic field. When the electron passes through the field, it curves. By changing the voltage in the coil, you change the "focus."

Also, you can't look through an eyepiece. Electrons are invisible to the human eye and, more importantly, they’d blind you or worse. The image has to be projected onto a fluorescent screen or captured by a digital sensor. You’re essentially looking at a translation of data, not a direct visual "reflection" like you do in a mirror.

Summary of Key Figures

To keep it straight, here’s the breakdown of the major players who created the electron microscope:

Ernst Ruska and Max Knoll are the undisputed "fathers." They built the first one in 1931. Ruska got the Nobel.

Reinhold Rudenberg filed the first major patents for the concept, though he didn't build the first working prototype.

James Hillier and Albert Prebus are the giants of the North American side, making the technology commercially viable and incredibly precise at RCA.

Manfred von Ardenne shifted the perspective, literally, by creating the scanning version that gives us 3D surface images.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you’re interested in seeing what these machines can do beyond a Google Image search, there are a few things you can actually do.

First, check out the Microcosmos project or the Nanolive databases. They offer high-resolution galleries of electron microscopy that are free to browse.

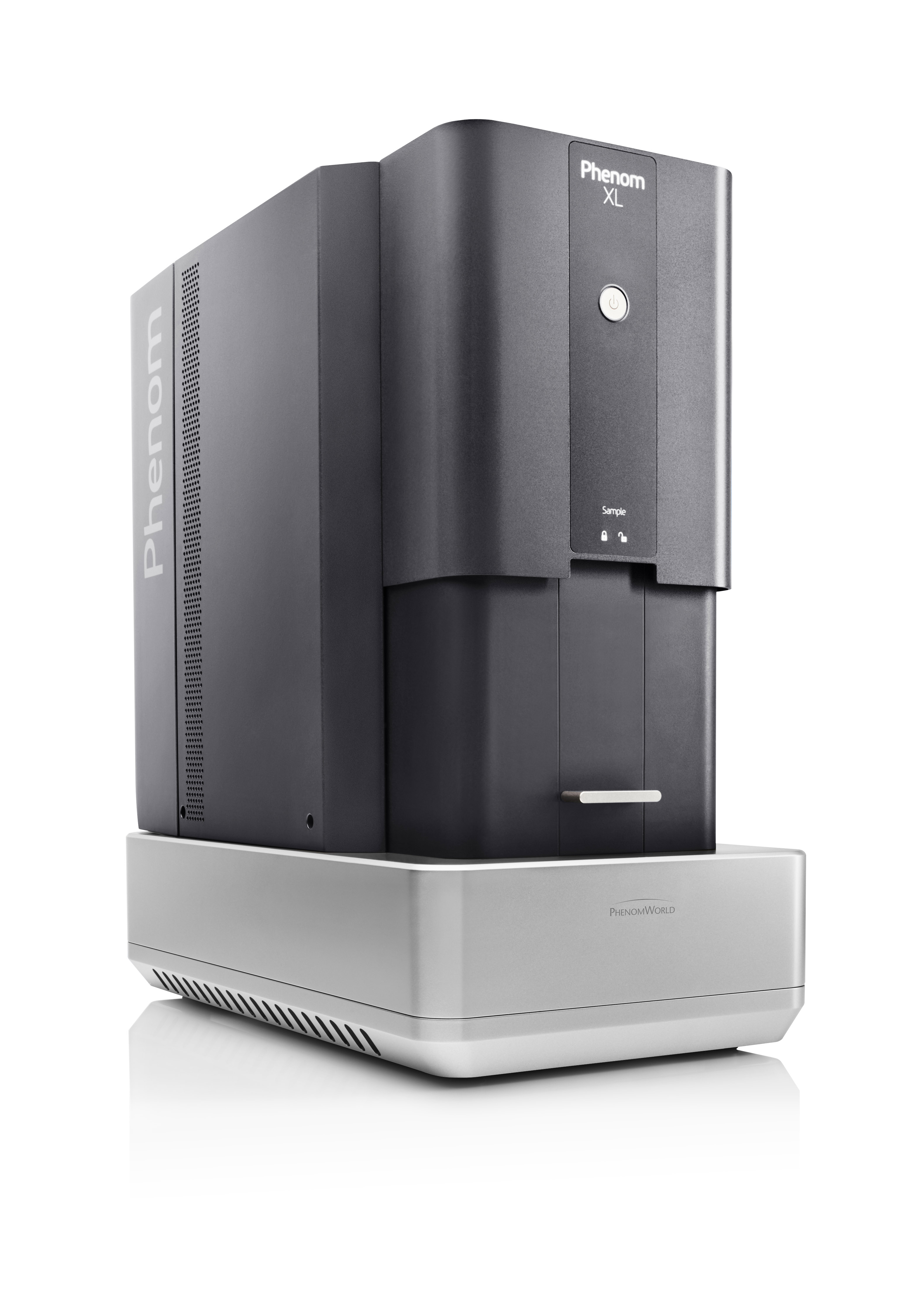

Second, if you’re a student or a hobbyist, look for "Desktop SEMs." They are still expensive (tens of thousands of dollars), but many universities and even some high schools now have them. Many facilities offer "outreach days" where they let the public bring in samples—like a dead bug or a piece of fabric—to see under the beam.

Finally, understand that the field is moving toward Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM). This is the current cutting edge. It involves freezing samples so fast that the water doesn't form crystals, allowing us to see proteins in their natural state. Jacques Dubochet, Joachim Frank, and Richard Henderson won the Nobel for this in 2017.

The invention of the electron microscope didn't just give us a better zoom lens. It gave us a map of a world we didn't even know existed. It proved that the universe is just as complex at the bottom as it is at the top.

To dig deeper into the actual imagery, you should visit the Royal Microscopical Society website, which maintains extensive archives on the evolution of these instruments and the people who built them. If you’re ever in Munich, the Deutsches Museum has Ruska’s original 1931 apparatus on display. Seeing it in person—this clunky, hand-built stack of metal and wire—really drives home how much can change when a couple of people decide to ignore what "physics" says is impossible.

Next Steps:

- Research the Difference: Look up "TEM vs SEM" images to see the visual difference between internal structure and surface detail.

- Visit a Virtual Lab: Search for "Virtual Electron Microscope" simulators provided by universities like Arizona State University (ASU) to try "focusing" a beam yourself.

- Explore Cryo-EM: Read about how Cryo-EM was used to map the spikes on the SARS-CoV-2 virus in record time during the 2020 pandemic.