Numbers don't lie, but they sure do get twisted. If you've spent more than five minutes on social media lately, you’ve probably seen some pretty heated debates about who commits the most violent crimes. People get angry. They shout. They cite half-remembered stats from a meme they saw three years ago. But when we actually look at the hard data—the stuff the FBI and the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) put out—the picture is a lot more complicated than a simple soundbite.

It’s not just about one group or one neighborhood.

Honestly, it’s about a messy intersection of age, gender, poverty, and geography. If you want to understand the "who," you have to understand the "where" and the "why." Crime isn't a personality trait. It’s a snapshot of a moment in time, usually involving people who have very little to lose and a lot of trauma they haven't dealt with yet.

Breaking Down the Demographics of Violence

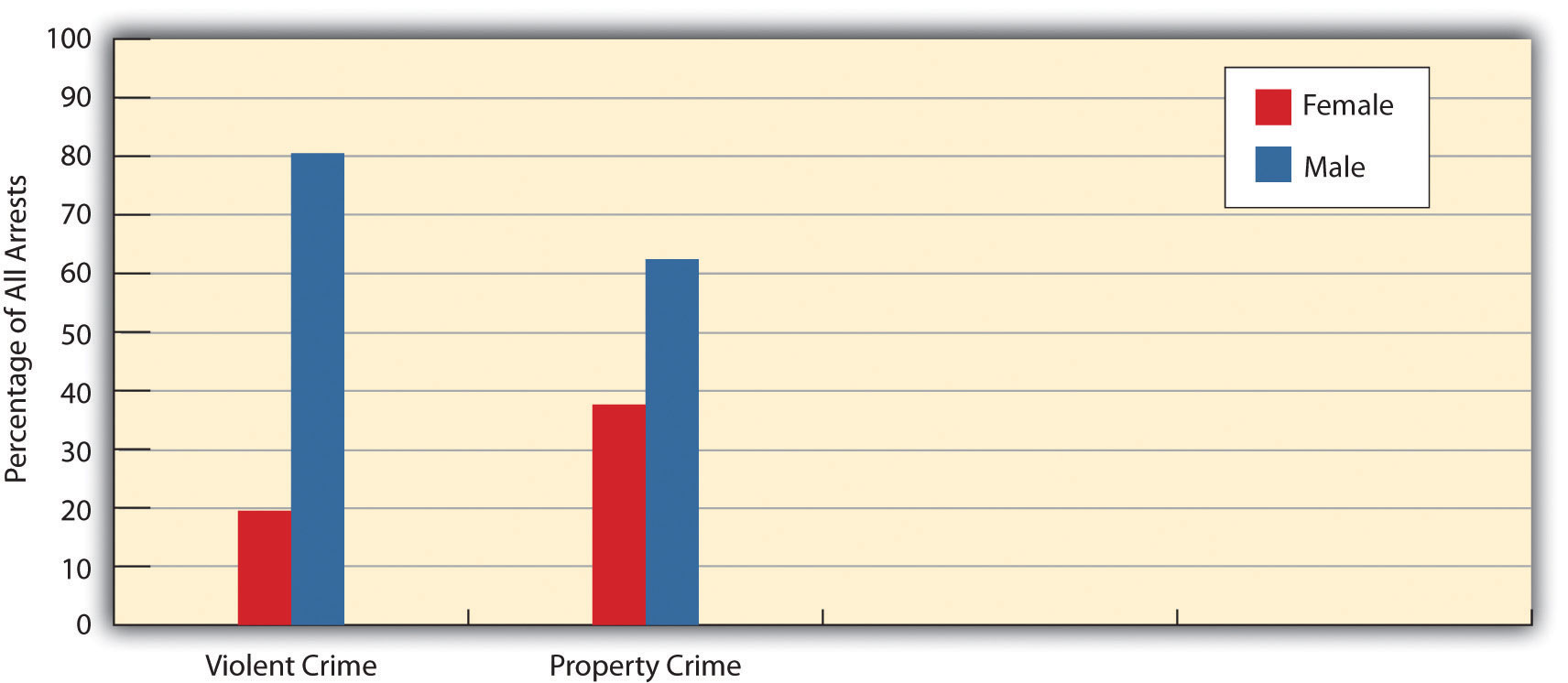

When we talk about who commits the most violent crimes, the most consistent factor across all history and every country isn't race or religion. It’s gender. Men commit the vast majority of violent offenses. In the United States, the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program consistently shows that men account for roughly 80% of arrests for violent crimes, including murder, rape, and robbery.

Why?

Sociologists like Michael Kimmel have spent decades looking at "aggrieved entitlement" and the way we socialize boys. It’s a mix of biology and culture. But it's not just "men" in general. It's young men. Specifically, men between the ages of 15 and 29. Criminologists call this the "age-crime curve." Basically, people start getting into trouble in their mid-teens, peak in their early twenties, and then—for the most part—they just stop. They grow up. They get jobs. They get tired of being in the system.

But for that narrow window of youth, the numbers are staggering.

The Role of Race and Reality

This is where the conversation usually gets uncomfortable. According to 2023 FBI data, Black or African American individuals are arrested for violent crimes at a rate that is disproportionate to their percentage of the population. Specifically, while making up about 13-14% of the U.S. population, they account for a much higher percentage of homicide and robbery arrests.

But wait.

If you stop there, you're missing the whole story. Most crime is "intraracial," meaning people generally commit crimes against people who look like them because people generally live near people who look like them. If you look at the work of researchers like Robert Sampson from Harvard, you find that when you control for poverty, the racial gap in violent crime starts to evaporate.

If you take a poor white neighborhood and a poor Black neighborhood with the same level of joblessness, the same number of single-parent households, and the same lack of grocery stores, the crime rates look remarkably similar. Poverty is the great equalizer when it comes to violence.

Geography and the "Concentrated Disadvantage"

Most violent crime isn't happening "everywhere." It's happening in specific blocks. Researchers call this "hot spot" policing, but from a sociological perspective, it’s about concentrated disadvantage.

Think about it this way.

If you live in a place where the schools are failing, the lead paint is peeling off the walls (which, by the way, is linked to impulse control issues), and there are no legitimate jobs, what do you think happens? Violence becomes a way to resolve disputes because the "official" channels—the police and the courts—aren't trusted or don't work. In many high-crime areas, "street justice" isn't a choice; it's a survival mechanism.

The Impact of Recidivism

We also have to talk about the "who" in terms of history. A very small percentage of the population is responsible for a very large percentage of the violent crime. These are often referred to as "chronic offenders."

A famous study in Philadelphia tracked a cohort of males and found that just 6% of them were responsible for over half of all the serious crimes committed by the entire group. These are individuals who often have significant neurodevelopmental issues, histories of severe physical abuse, or untreated substance abuse disorders. When we ask who commits the most violent crimes, we’re often talking about a tiny fraction of people who are caught in a cycle of incarceration and release without ever getting the mental health support they actually need.

📖 Related: Is the Santa Monica Pier on Fire? What’s Actually Happening Right Now

The Economic Engine of Violence

You can't talk about violence without talking about the "underground economy." In many cities, violent crime is linked directly to the drug trade or gangs. But why do people join gangs?

Economics.

If you can make $500 a week working a grueling job at a fast-food joint or $2,000 a week standing on a corner, and you have no hope of going to college, the math is pretty simple for a 19-year-old with no guidance. The violence isn't the goal; it's the cost of doing business in an unregulated market. When a "legal" business has a dispute, they sue. When an "illegal" business has a dispute, they use a gun.

What the Media Gets Wrong

TV news loves a "random act of violence." It scares people. It gets ratings. But the reality is that truly random violent crime is incredibly rare.

In the majority of homicides and aggravated assaults, the victim and the perpetrator knew each other. It was an argument that escalated. It was a domestic dispute. It was a debt that went unpaid. The "boogeyman" jumping out of the bushes is a tiny sliver of the actual data. Most violence is personal.

Moving Toward Real Solutions

So, what do we do with this info? If we know that young men in high-poverty areas are the ones most likely to be involved in the system, we can stop guessing and start fixing.

- Targeted Intervention: Programs like "Cure Violence" treat crime like a public health issue. They use "violence interrupters"—people who used to be in the life—to talk people down before they pull a trigger. It works.

- Early Childhood Support: This sounds "soft," but it's actually hard-nosed crime prevention. Better nutrition, lead abatement, and early education keep kids on the right path before the "age-crime curve" even starts.

- Economic Opportunity: If you want to lower the crime rate, give people something to lose. A man with a mortgage and a 401k is a lot less likely to risk his life over a "respect" issue on a street corner.

The data on who commits the most violent crimes tells us that violence is a symptom, not a cause. It's the end result of a long chain of failures—educational, economic, and social. If we only focus on the final link in that chain (the arrest), we're going to keep running in circles.

Understanding the demographics of crime isn't about pointing fingers or validating prejudices. It’s about looking at the map of where our society is broken and deciding to actually do the work to fix it. We have the data. We know who is hurting and who is causing hurt. The question is whether we care enough to change the conditions that make violence feel inevitable for so many people.

Actionable Steps for Community Safety

- Support Local Mentorship: Look for organizations in your city that specifically work with at-risk youth aged 14-24. This is the peak window for crime prevention.

- Advocate for Lead Abatement: Check local housing policies. Reducing environmental toxins is one of the most cost-effective ways to lower long-term violent crime rates.

- Focus on Re-entry: Support "ban the box" initiatives and vocational training for formerly incarcerated individuals to break the recidivism cycle.

- Invest in "Green Space": Studies show that simply cleaning up vacant lots and adding lighting to parks can reduce local violent crime by double digits.

The numbers are heavy, but they aren't a life sentence for our cities. By focusing on the root causes—poverty, youth, and lack of opportunity—we can move the needle in a way that purely punitive measures never have.