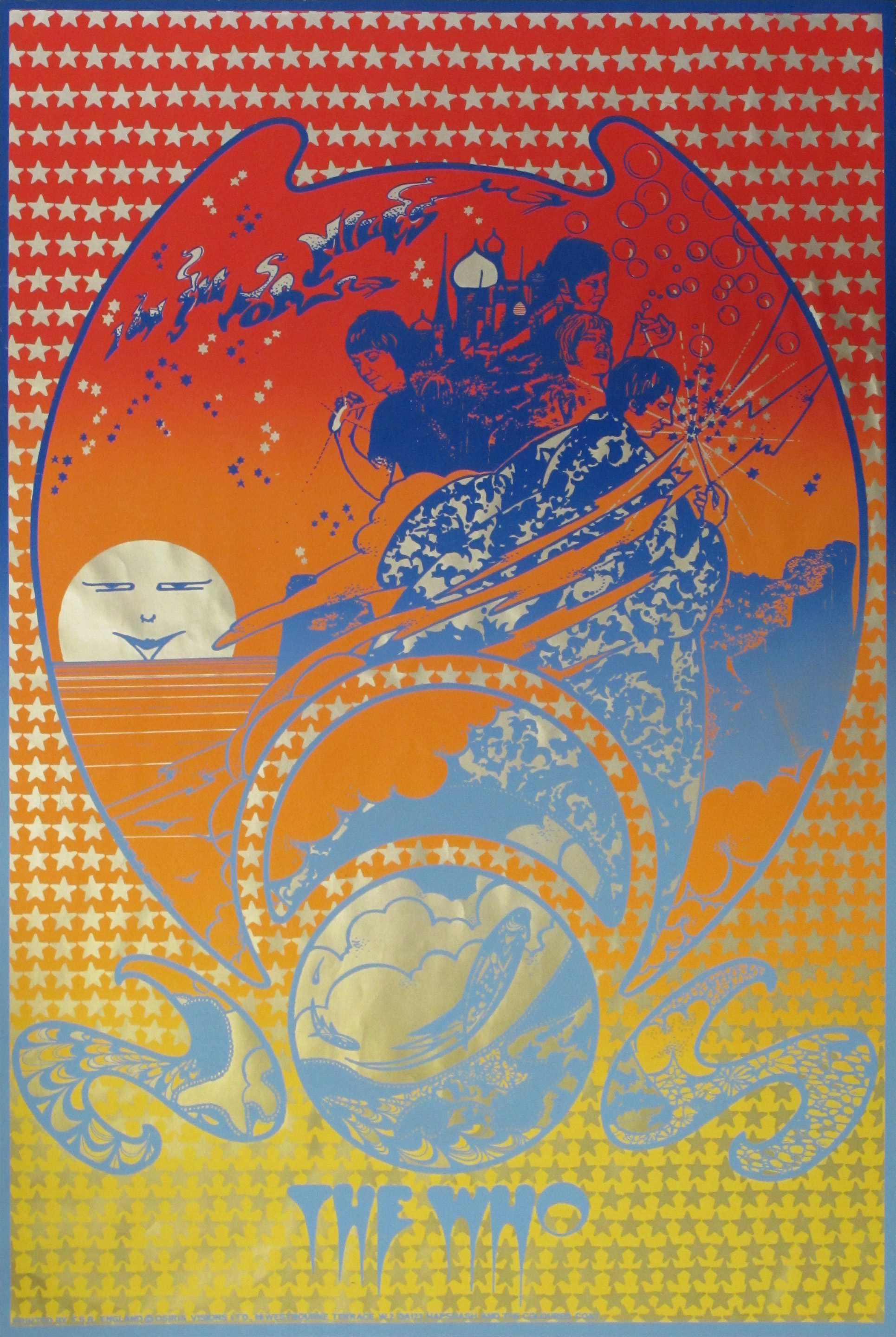

You’re standing on a beach. You look at the horizon. It seems like the end of the world, right? Honestly, for most of us, it is. Our eyes just aren't built to pierce through the thick soup of the atmosphere or resolve tiny details from a massive distance. But some people—and certainly some animals—live in a completely different visual reality. When we talk about who can see for miles, we aren't just talking about a poetic line from a classic The Who song. We are talking about the physical limits of the human eye, the staggering biological tech of raptors, and the strange cases of people like Veronica Seider.

Eyesight is weirdly subjective. You might think you see "perfectly," but compared to a wedge-tailed eagle, you’re basically navigating through a sheet of wax paper.

The Human Limit: Can We Actually See for Miles?

Flat ground is the enemy of distance. Because the Earth is a sphere, the horizon for a person of average height is only about 3 miles away. That's it. Your "seeing for miles" is capped by the very curve of the planet. But if you climb a hill? Suddenly, the geometry changes. From the top of Mount Everest, you could theoretically see hundreds of miles if the air was perfectly clear.

But "seeing" and "resolving" are two different things.

You can see the Andromeda Galaxy with the naked eye on a dark night. That’s 2.5 million light-years away. So, in one sense, everyone can see for millions of trillions of miles. But if you’re trying to read a license plate from a block away, that’s where most of us fail. Human visual acuity is usually measured by the Snellen chart—the classic 20/20 standard. This means you can see at 20 feet what a "normal" person sees at 20 feet.

Some people are 20/10. That’s elite. They can see things from 20 feet away that the rest of us need to be 10 feet away to spot. Then there is the legend of Veronica Seider. In the 1970s, researchers at the University of Stuttgart identified Seider, a dental student, as having visual acuity roughly 20 times better than the average person. She could allegedly identify people from over a mile away. While some of the more hyperbolic claims about her sight remain debated in optometry circles, she remains the benchmark for the extreme edge of human capability.

📖 Related: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

What Makes an Eye Superior?

It comes down to the density of the hardware. Think of your eye like a digital camera. The retina is the sensor. The "pixels" on that sensor are your photoreceptors—rods and cones.

Humans have a tiny spot in the center of the retina called the fovea. This is where our sharpest vision lives. We have about 200,000 cones per millimeter in that spot. It sounds like a lot until you look at a hawk. A hawk has about a million.

Imagine trying to see a rabbit in a field from a skyscraper. To you, it’s a brown blur. To the hawk, it’s a 4K movie. This is who can see for miles with actual utility. They aren't just seeing the distance; they are processing the data within that distance. Raptors have deeper foveae, which actually act like a telephoto lens, magnifying the center of their field of view. It’s built-in binoculars.

- Atmospheric Interference: Dust, water vapor, and heat haze (refraction) scatter light. Even if you had "infinite" vision, the air itself eventually turns everything into a gray wall.

- The Curvature of the Earth: Unless you have height, the ground literally drops away from your line of sight.

- Neural Processing: Your brain does a lot of the heavy lifting. People who spend their lives looking at the sea or the desert—like the Moken "sea nomads"—often develop better visual processing for those specific environments.

The Case of the Moken Children

The Moken people live in the Mergui Archipelago in the Andaman Sea. They are famous for their "dolphin-like" ability to see underwater.

Biologist Anna Gislén studied Moken children and found their underwater vision was twice as sharp as European children. How? They weren't born with different eyes. They learned to constrict their pupils and change the shape of their lenses while underwater. Most people’s eyes don't do that. It’s a physical adaptation to a lifestyle. If you want to know who can see for miles (or at least see where no one else can), look to the people whose survival depends on it.

👉 See also: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

Gislén later showed that any child could be trained to do this. It’s a reminder that "vision" is partly a skill, not just a biological gift.

Technology and the Extension of Sight

If nature won't give it to us, we build it. We’ve moved past simple glass binoculars. Modern spotting scopes used by birders or long-range shooters use extra-low dispersion (ED) glass to prevent "fringing," where colors bleed at the edges of an object.

Then there’s digital enhancement. We are entering an era where AI-augmented goggles can "de-haze" the atmosphere in real-time. This isn't science fiction. Pilots use Head-Up Displays (HUDs) that use infrared to see through clouds. When we ask who can see for miles in 2026, the answer is often "anyone with a high-end thermal optic."

But there’s a cost. Over-reliance on screens and close-up work is causing a global myopia (nearsightedness) epidemic. We are losing our long-distance "muscles" because we spend 10 hours a day looking at something 12 inches from our faces.

The Myth of the "Eagle Eye"

People toss the term "eagle eye" around constantly. Let's be specific. An eagle can see a rabbit moving from two miles away. Their eyes are actually larger than their brains by volume. Because their eyes are so big, they can't really move them in the sockets. That’s why birds of prey have such twitchy, fast-moving necks. They have to move their whole head to track you.

✨ Don't miss: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

Also, they see colors we can't even imagine. They see ultraviolet light. A kestrel can fly over a field and see the UV-reflective trails of rodent urine. To the bird, the field is a map of glowing neon signs leading straight to dinner. We are essentially colorblind by comparison.

How to Protect and Improve Your Long-Range Vision

You probably can't train yourself to have 20/2 vision like Veronica Seider, but you can stop your distance vision from tanking.

- The 20-20-20 Rule is Mandatory. Every 20 minutes, look at something 20 feet away for 20 seconds. It relaxes the ciliary muscles in your eye. If you don't do this, those muscles get "locked" into a near-focus state, leading to digital eye strain and worsening myopia.

- Get Outside. Studies have shown that children who spend more time in natural sunlight have lower rates of nearsightedness. It's not just about looking far away; it's about how the light triggers dopamine release in the retina, which keeps the eye from growing too long (the physical cause of myopia).

- Contrast Matters. Vision isn't just about "sharpness." It's about contrast sensitivity. Eating foods high in lutein and zeaxanthin—think kale, spinach, and eggs—helps build the macular pigment that filters blue light and improves contrast.

- Polarization. If you are trying to see for miles over water or snow, use polarized lenses. They cut the horizontal glare that "blinds" the eye to the details beneath or beyond the reflection.

Beyond the Horizon

We often think of sight as a passive thing. We just open our eyes and the world happens. But who can see for miles is usually a question of intent. The sailor sees the slight change in water color that signals a reef. The hiker sees the subtle movement of a deer's ear against a forest background.

Our ancestors survived because they could spot a predator on the savanna from a massive distance. We’ve traded that long-range survival instinct for the ability to read tiny text on a glowing rectangle.

If you want to experience what "seeing for miles" really feels like, you have to get away from the city. You need a high vantage point—a mountain peak or a skyscraper—on a day with low humidity. Look for the furthest thing you can possibly identify. Then, try to see the texture on it. You'll realize that your eyes are capable of much more than you give them credit for; they just haven't had a reason to try in a long time.

Actionable Steps for Better Distance Vision

- Audit your workspace: Ensure your monitor is at least an arm's length away. The closer it is, the harder your eyes work to maintain focus, which degrades your "distance" flexibility over time.

- Practice Active Looking: When outdoors, consciously try to resolve details on the furthest visible objects, like the leaves on a distant tree or the windows on a far-off building. This helps maintain visual processing speed.

- Check your Vitamin A and Zinc levels: These are the chemical foundations of the rhodopsin in your eyes, which allows you to see in low light and maintain retinal health.

- Invest in Quality Glass: If you genuinely need to see for miles for a hobby like birdwatching or hunting, don't buy cheap binoculars. Cheap glass causes eye fatigue (your brain trying to correct for the lens's flaws). Look for "fully multi-coated" lenses and Bak-4 prisms.

The world is much bigger than the 10 feet around your desk. Go out and actually look at it.