You probably think you know the rule. Every four years, we add a day to February. Easy, right? Well, honestly, if that were the only rule, your summer vacation would eventually end up in the middle of a blizzard. It sounds dramatic, but the math doesn't lie.

The question of which years are leap years is actually a bit more "it's complicated" than a simple "multiply by four." We’re basically trying to sync a man-made calendar with the messy, wobbling orbit of a giant rock spinning through space. It turns out the Earth doesn't take exactly 365 days to circle the sun. It takes about 365.24219 days. That tiny decimal—that "point two four two"—is a total headache for astronomers and has been for centuries.

The Three Rules of the Leap Year

To figure out which years are leap years, you have to pass a three-step logic test. Most people stop at the first step. That’s a mistake.

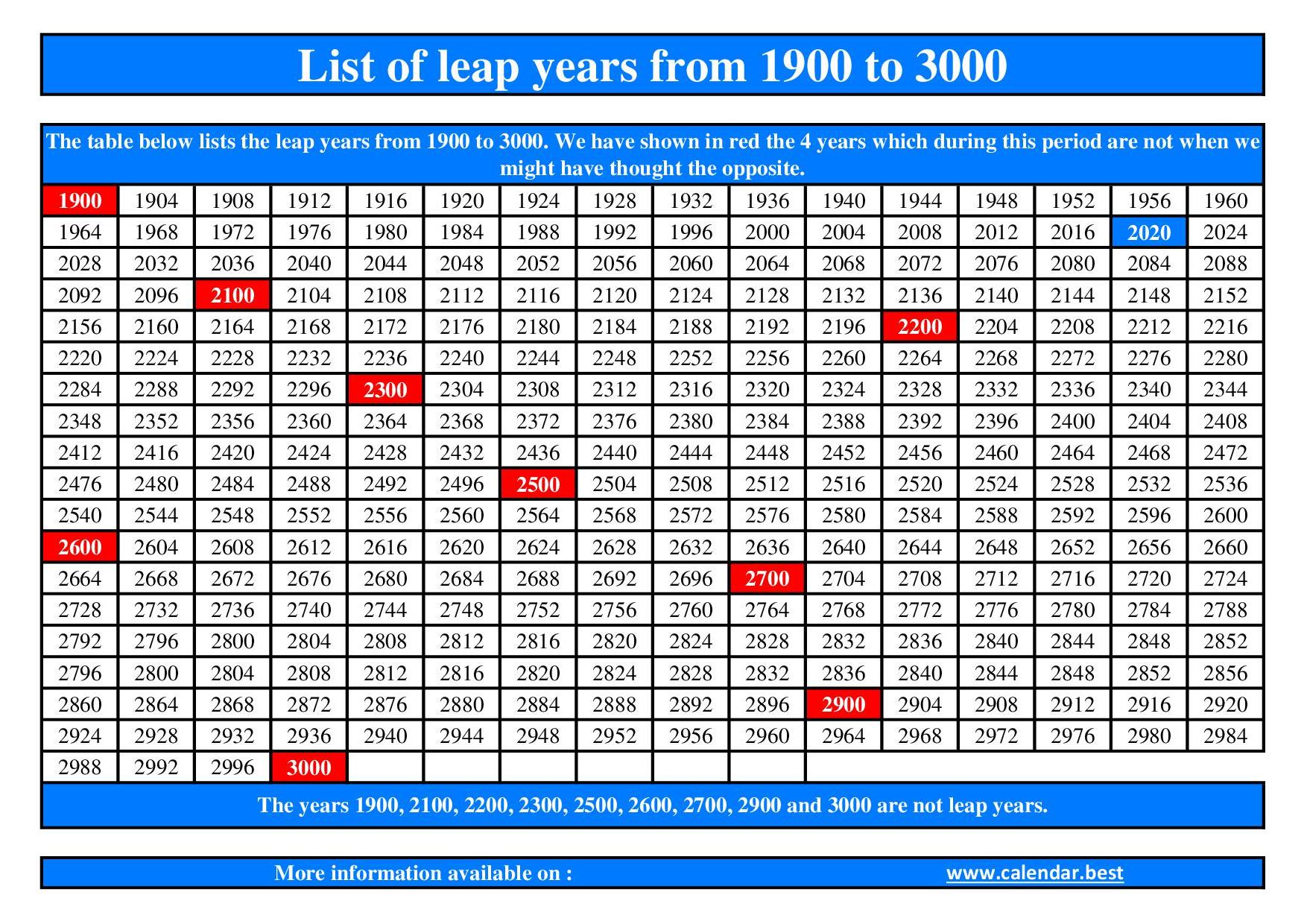

First, the year must be evenly divisible by 4. This is the one we all learned in elementary school. 2024? Yes. 2028? Yes. 2031? No chance. But then things get weird. If a year is divisible by 100, like 1900 or 2100, it is actually not a leap year. This catches people off guard all the time. But wait, there’s a final twist. If the year is divisible by 400, it becomes a leap year again.

This is why the year 2000 was so special. It was a "century year" that was also divisible by 400. If you were alive then, you witnessed a rare calendrical event that won't happen again until the year 2400. Most people didn't even notice because the calendar just did its thing, but for math nerds, it was a big deal.

Why do we even bother with this?

Imagine we ignored that extra quarter-day. After 100 years, our calendar would be off by about 24 days. In a few centuries, the Fourth of July would be happening in the autumn. Farmers wouldn't know when to plant. The seasons would drift away from the dates we’ve assigned to them. We use these extra days to "reset" the clock.

📖 Related: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), this system—known as the Gregorian Calendar—is accurate to within about one day every 3,236 years. It’s not perfect, but it’s close enough for government work.

The History of the "Glitch"

We haven't always had this figured out. Julius Caesar was the one who really pushed the "every four years" rule back in 46 BCE. It was a massive improvement over what they had before, which was basically a chaotic mess where politicians would just add months whenever they felt like it to stay in office longer.

But the Julian calendar had a flaw. It assumed the year was exactly 365.25 days long.

That 11-minute difference between 365.25 and 365.2422 seems like nothing. It’s a coffee break. But over 1,600 years, those eleven minutes added up to ten whole days. By the late 1500s, the Catholic Church noticed that Easter was drifting further and further away from the spring equinox. Pope Gregory XIII finally stepped in. He dropped ten days from the calendar in 1582 to fix the drift and introduced the "divisible by 400" rule to prevent it from happening again.

People were furious. There are stories of riots in the streets because people thought the government was literally stealing ten days of their lives. Imagine waking up on October 4th and being told it’s actually October 15th. It was a mess.

👉 See also: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

Spotting a Leap Year: A Quick Reference

If you're trying to calculate which years are leap years for a project or just to settle a bet, here is the breakdown of the upcoming schedule:

- 2024: Leap Year (Divisible by 4)

- 2028: Leap Year (Divisible by 4)

- 2032: Leap Year (Divisible by 4)

- 2100: NOT a Leap Year (Divisible by 100, but not 400)

See that 2100? It’s the one that trips up software developers. In fact, many computer systems had glitches in the past because programmers forgot the "century rule." If you're planning on being around in 76 years, don't expect a February 29th.

The Leapling Experience

What if you're born on February 29th? You're a "leapling."

Socially, it's a bit of a nightmare. Many online forms don't even have "February 29" as a drop-down option. Legally, most states and countries have to pick a day for you to officially turn a year older for things like driving or buying a drink. Usually, it's March 1st.

There’s a famous family in Norway, the Henriksens, who actually hold a world record because three of their children were born on consecutive leap days: 1960, 1964, and 1968. The odds of that are astronomical. You have a better chance of winning the lottery while being struck by lightning. Sorta.

✨ Don't miss: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

The "Leap Second" Controversy

Just when you think you understand which years are leap years, science throws another curveball: the leap second.

The Earth's rotation is actually slowing down slightly over time because of tidal friction from the moon. To keep our ultra-precise atomic clocks in sync with the Earth's physical rotation, we occasionally have to add a "leap second."

However, tech companies like Meta and Google hate leap seconds. They can cause massive server crashes because computers don't handle a 61-second minute very well. In 2022, international scientists and government representatives voted to eventually scrap the leap second by 2035. We’re moving toward a system where we might just let the discrepancy build up for a century and then add a "leap minute" instead.

Technical Checklist for Future Dates

To be 100% sure about a specific year, run it through this mental flow:

- Divide by 4. If there’s a remainder, it’s a common year.

- Check for double zeros. If the year ends in 00, it must be divisible by 400 to count.

- Confirm the month. Remember that a leap year only adds a day to February.

This matters more than you think for things like interest rates on loans, insurance premiums, and even prison sentences. Calculations based on a 365-day year can get messy when that 366th day pops up.

Summary of Actionable Steps

Determining which years are leap years is about more than just checking a calendar; it's about understanding the mechanics of our time-keeping. If you are managing long-term databases or financial planning, keep these points in mind:

- Audit your software: Ensure any date-handling code accounts for the "Century Rule" (years divisible by 100 but not 400 are not leap years).

- Adjust long-term contracts: If you have a contract spanning decades, specify how "annual" rates are calculated in leap years to avoid disputes over that extra day of interest.

- Mark 2100: If you're building something for the next century, remember that 2100 is the "exception year" that will catch people off guard.

- Celebrate the 29th: Use the extra 24 hours to do something you usually don't have time for. It's a "free" day provided by the quirks of planetary physics.