Energy is weird. We talk about it like it's a battery or a fuel tank, but in the wild, it's just one long, messy chain of eating and being eaten. If you’ve ever wondered which organisms pass energy to the secondary consumers, the short answer is the primary consumers. But honestly? That answer is a bit too simple for how complex nature actually is.

Think about a field of grass. The grass doesn't do much other than sit there and soak up the sun. Then a grasshopper comes along. It munches away, taking that solar energy stored in plant sugars and turning it into "grasshopper energy." Now, when a bluebird swoops down and grabs that grasshopper, the energy moves again. In this specific scenario, the grasshopper is the one passing that energy up the ladder to the secondary consumer—the bird. It’s a literal life-or-death handoff.

The Middlemen: Why Primary Consumers Are the Gatekeepers

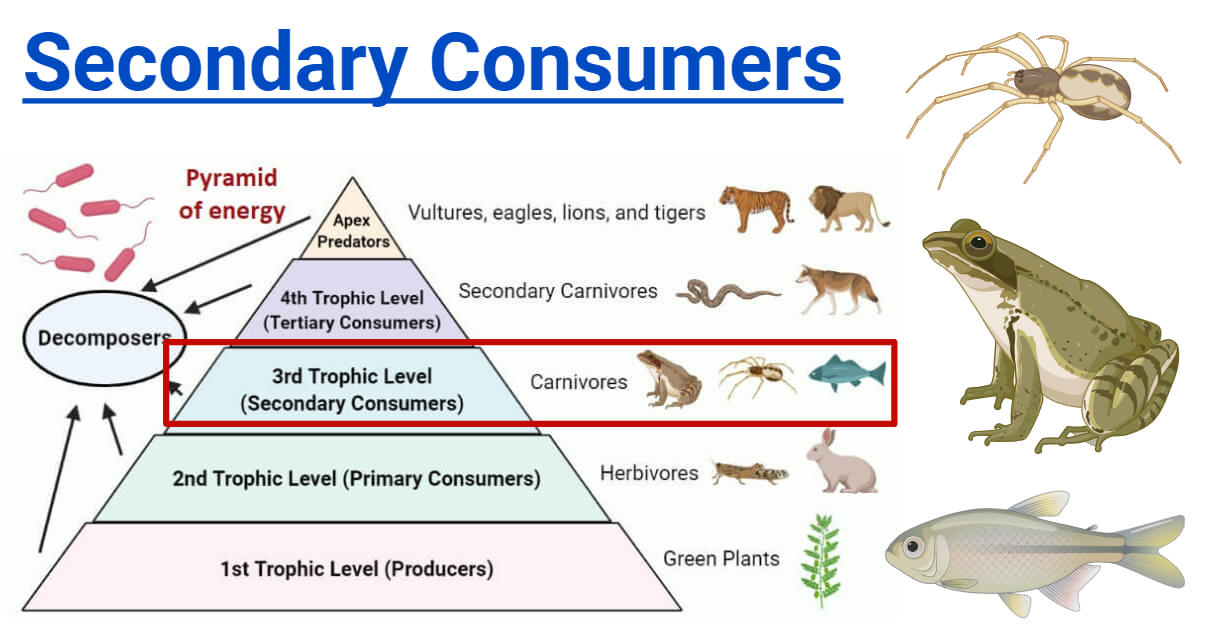

To understand which organisms pass energy to the secondary consumers, you have to look at the primary consumers, also known as herbivores. They are the essential bridge. Without them, the energy captured by plants from the sun would just stay locked in cellulose and starch. Carnivores can't eat grass. Well, they can, but they can't digest it for energy.

Primary consumers come in all shapes and sizes. It isn't just cows and bunnies. In a pond, it’s microscopic zooplankton eating algae. In a forest, it might be a deer or even a tiny caterpillar. These organisms do the "heavy lifting" of converting plant matter into animal tissue. By the time a secondary consumer—like a fox, a frog, or a small hawk—gets a meal, they are receiving energy that has already been filtered through at least one other living thing.

It's a leaky system.

📖 Related: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

Raymond Lindeman, a pioneer in ecology, famously described the "10% Rule" back in the 1940s. It's not a perfect law, but it's a solid rule of thumb. Basically, when a primary consumer passes energy to a secondary consumer, about 90% of that energy is already gone. The herbivore used it to breathe, move, poop, and just stay warm. Only a tiny fraction—the stuff actually built into the herbivore's muscles and fat—makes it to the next level. This is why you see thousands of zebras but only a handful of lions. There just isn't enough energy moving up the chain to support a massive population of secondary consumers.

Breaking Down the Specific Groups

When we ask which organisms pass energy to the secondary consumers, we are looking at several distinct biological groups depending on the environment. It's never just one thing.

Terrestrial Herbivores

On land, these are your classic examples. Insects are arguably the most important. Think about the sheer volume of beetles, aphids, and caterpillars. They are the primary energy source for secondary consumers like spiders, birds, and shrews. If the insects disappeared, the energy flow would hit a brick wall. Then you have the larger mammals—rodents, rabbits, and deer—feeding the larger predators.

Aquatic Zooplankton and Small Fish

In the ocean or a lake, the "plants" are often invisible phytoplankton. The organisms that pass energy to secondary consumers here are usually zooplankton or small "forage fish" like sardines or minnows. These little guys eat the plankton and then get eaten by bigger fish, squid, or seabirds. In these ecosystems, the "primary consumer" phase can be incredibly fast-paced because the life cycles are so short.

👉 See also: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

The Decomposer Loophole

Here is something people usually miss. Sometimes, the organisms passing energy to secondary consumers aren't herbivores at all. They are detritivores. Think of worms or woodlice. They eat dead stuff. If a robin eats an earthworm, that robin is a secondary consumer, but the "energy passer" was an organism eating decaying leaves instead of live ones. Nature doesn't always follow the neat "green plant to herbivore" line we see in textbooks.

Why the "Efficiency" of the Handoff Matters

The health of an entire ecosystem depends on how well these primary consumers do their jobs. If a primary consumer population crashes—maybe because of a disease or a drought—the secondary consumers are the first to feel the pinch. They are "energy-hungry." Because they sit higher on the pyramid, they are much more vulnerable to fluctuations in the food supply.

Consider the "trophic cascade." This is a fancy term for what happens when you mess with one level of the chain. In Yellowstone National Park, when wolves (tertiary consumers) were gone, the elk (primary consumers) overpopulated. They ate so much willow and aspen that the birds and beavers (secondary consumers in different ways) didn't have the resources or the "energy handoff" they needed to survive. It’s all connected. The energy flow isn't a straight line; it's a web.

The Complexity of Omnivores

Humans make this whole "which organisms pass energy" question really messy. We are often secondary consumers. When you eat a burger, the cow (primary consumer) is passing energy to you. But if you eat a salad, you're the primary consumer. If you eat a piece of salmon that ate a smaller fish that ate larvae, you're actually a tertiary or quaternary consumer.

✨ Don't miss: Human DNA Found in Hot Dogs: What Really Happened and Why You Shouldn’t Panic

Many animals are like us. A bear might eat berries (acting as a primary consumer) or it might eat a fish (acting as a secondary or tertiary consumer). This flexibility is a huge survival advantage. If one energy source fails, you just switch to another. However, for specialists—like a black-footed ferret that almost exclusively eats prairie dogs—the specific organism passing them energy is the only thing keeping them from extinction.

Reality Check: It’s All About Carbon

At the molecular level, when we talk about energy being passed, we’re talking about carbon bonds. Plants take carbon dioxide from the air and, using sunlight, "fix" it into glucose. That glucose is energy. Every time an organism eats another, those carbon bonds are broken to release energy for the cells.

This is why "biomass" is so important. The total weight of all primary consumers in an area tells you exactly how much energy is available for the secondary consumers. You can't have more predator weight than prey weight. It’s physically impossible.

Actionable Steps for Understanding Your Local Ecosystem

Understanding how energy moves isn't just for biology class; it changes how you look at your own backyard or local park. If you want to see this in action and support the "energy handoff" in your area, here is what you can actually do:

- Plant native species. Non-native plants often can't be eaten by local insects. If the insects (primary consumers) can't eat the plants, they can't pass energy to the birds (secondary consumers). You end up with an "energy desert."

- Stop the "Scrubbing." Many people clean up every dead leaf and fallen branch. By leaving some "mess," you support detritivores like beetles and worms. These are the organisms that pass energy to secondary consumers like toads and songbirds.

- Observe the "Trophic Levels" in real-time. Next time you're outside, find a plant and wait. See who eats it. Then, wait and see if something eats that bug. You’re watching the literal transfer of solar-turned-chemical energy.

- Reduce chemical pesticides. Killing off the primary consumers (the "pests") sounds great for your garden, but it starves the secondary consumers. It breaks the chain. Using integrated pest management allows the natural energy flow to control the population for you.

Energy flow is the heartbeat of the planet. While we often focus on the "top predators," they are entirely dependent on the humble herbivores and detritivores that do the hard work of collecting energy from the bottom of the pyramid.