Ever get that feeling where you're staring at a multiple-choice question and every single answer looks like a slightly different flavor of "the same thing"? It happens a lot in biology. If you’re looking to pinpoint which of these describes a genome, you're likely sifting through terms like DNA, genes, chromosomes, and alleles. It's confusing. Honestly, even for people who work in labs, the terminology can get a bit soupy if you aren't careful.

A genome isn't just a fancy word for a gene. It’s the whole kit and caboodle.

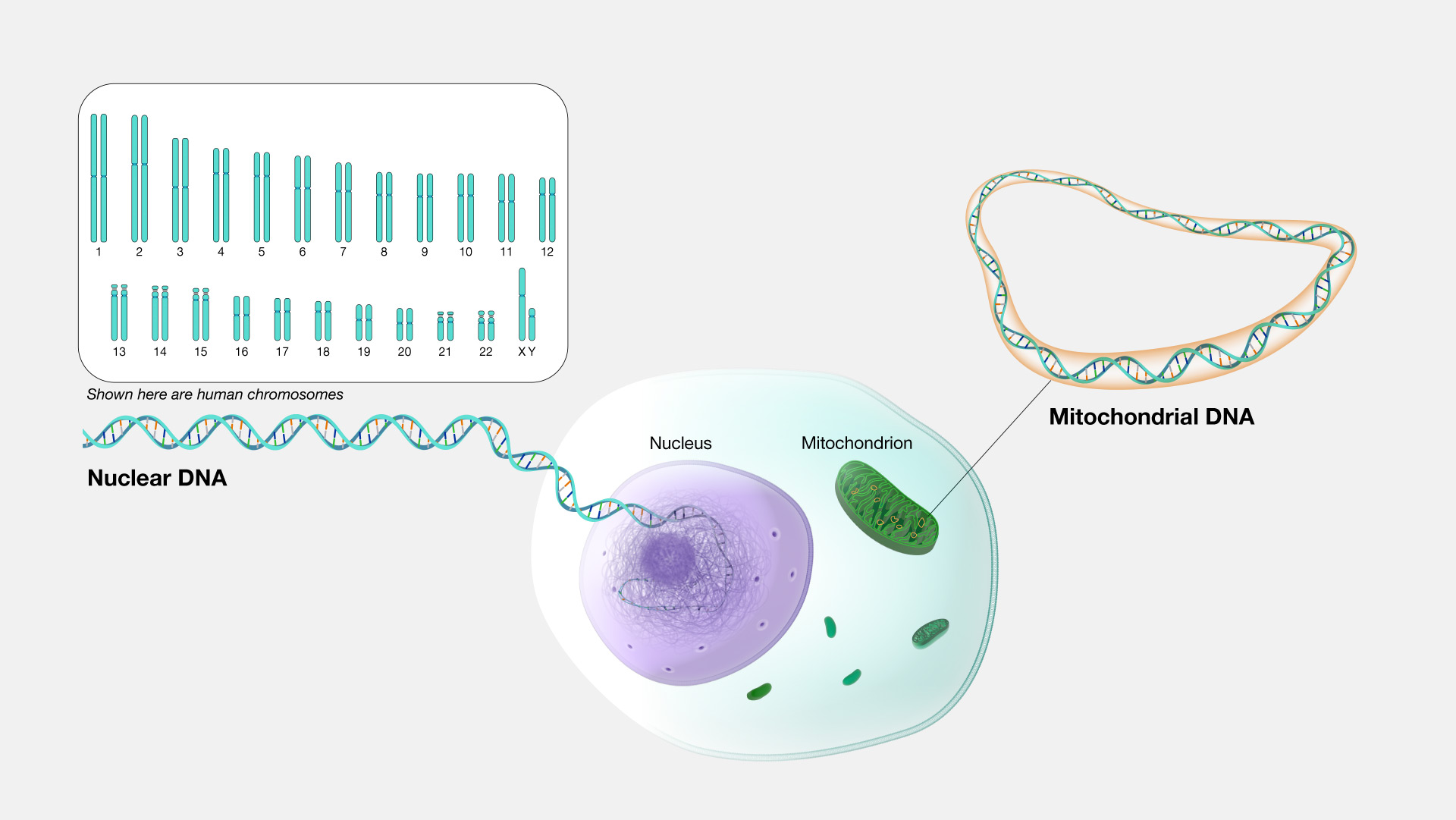

Think of it this way: if your DNA is the ink and a gene is a single sentence, the genome is the entire library. Every book, every shelf, even the weird instruction manual for the fire extinguisher in the hallway. It is the complete set of genetic instructions found in a cell. In humans, that means all 23 pairs of chromosomes and that little bit of extra DNA hiding out in your mitochondria.

Why the Definition Trips Us Up

Most students or curious readers get stuck because they think a genome is just "the stuff that makes you, you." While true in a poetic sense, scientifically, it's more specific. A genome includes both the coding sequences—the genes that actually build proteins—and the non-coding sequences. For a long time, scientists called that non-coding stuff "junk DNA." We were wrong. We now know that "junk" acts like a massive control panel, turning genes on and off like a complicated light show.

So, if you are looking at a list of options for which of these describes a genome, the correct answer is almost always going to be "the total digital or physical collection of an organism's genetic material."

It’s big. Like, really big. If you printed out the human genome, you’d have a stack of paper 300 feet tall. You’d be reading for a century.

The Components That Actually Matter

To really get why one description fits better than another, you have to look at the hierarchy. It’s a nesting doll situation.

💡 You might also like: Can DayQuil Be Taken At Night: What Happens If You Skip NyQuil

At the smallest level, you have the bases: Adenine, Thymine, Cytosine, and Guanine. You know them as A, T, C, and G. These are the letters. When you string them together in a specific order, you get a gene. But here is the kicker—genes only make up about 1% to 2% of the entire human genome.

Wait.

Only 2%?

Yeah. The rest is regulatory sequences, introns, and repetitive elements. If you define a genome only as "a collection of genes," you’re missing 98% of the picture. That’s why a precise description must include the entirety of the hereditary information.

The Mitochondrial Exception

People often forget about the mitochondria. We all learned in middle school that it's the "powerhouse of the cell." But it also has its own tiny, circular genome. When we talk about the human genome in a clinical sense, we are usually talking about the nuclear genome (the stuff in the nucleus), but a truly accurate biological description includes those mitochondrial circles too.

Genomics vs. Genetics: A Key Distinction

People use these words interchangeably. They shouldn't.

📖 Related: Nuts Are Keto Friendly (Usually), But These 3 Mistakes Will Kick You Out Of Ketosis

Genetics is usually the study of single genes and how traits are passed down. Think Mendel and his peas. Genomics is the study of the genome in its entirety. It’s the difference between studying one specific brick and studying the architecture of the entire skyscraper.

If you are looking for which of these describes a genome, look for the word "organism." A genome is specific to the individual or the species. My genome is unique to me (unless I have an identical twin), but it follows the "map" of the human species genome.

Real World Impact: Why Accuracy Matters

In 2003, the Human Genome Project finished its first big draft. It cost billions. Today, you can get a decent look at your own SNPs (Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms) for the price of a nice dinner out. But having the map isn't the same as knowing how to drive.

Take the BRCA1 gene. Most people know it’s linked to breast cancer. But the gene itself isn't the "cancer gene." Everyone has BRCA1. It’s actually a tumor suppressor. The problem arises when there’s a specific mutation within that part of the genome. Understanding the genome as a whole allows doctors to see not just the mutation, but how other parts of your DNA might be compensating for it or making it worse. This is the bedrock of "precision medicine."

Common Misconceptions Found in Multiple Choice Questions

If you’re taking a test or reading a textbook, you’ll see some "distractor" answers. Let's knock those down:

- "A genome is a single strand of DNA." Nope. That’s just a molecule. A genome is the collection of all those molecules.

- "A genome is the same as a genotype." Close, but no. A genotype usually refers to the specific alleles at a certain location. The genome is the broader container.

- "A genome is only found in the nucleus." We already covered this—shoutout to the mitochondria!

- "All genomes are the same size." Not even close. A Japanese canopy plant (Paris japonica) has a genome 50 times larger than ours. Size doesn't always equal complexity. We have about 3 billion base pairs. Some lungfish have 43 billion.

Nature is weird.

👉 See also: That Time a Doctor With Measles Treating Kids Sparked a Massive Health Crisis

Mapping the Future of Genomic Data

We are currently in the era of "Pangenomics." Instead of just having one reference genome that represents "humans," scientists are trying to map the diversity of the entire species. This is because the original reference genome was heavily skewed toward people of European descent.

By broadening our description of the human genome to include diverse populations, we find new variations that affect how people respond to drugs or why certain diseases hit some communities harder than others. It turns out that which of these describes a genome depends heavily on whose genome you are looking at.

The Role of CRISPR and Editing

When we talk about "editing the genome," we are talking about using molecular scissors to change those letters. It’s high-stakes stuff. If you change a gene in a lung cell, it stays there. If you change the "germline" genome (sperm or eggs), you change the instructions for every generation that follows. That is the power of the genome—it is a living, breathing record of history and a blueprint for the future.

Actionable Takeaways for Identifying the Genome

If you need to identify the correct description for a test, a paper, or just to satisfy your own curiosity, keep these three checkpoints in mind. They are the "must-haves" for any definition that claims to be accurate.

- Total Content: It must mention the "complete" or "total" set of DNA. If it says "some" or "just the genes," it's wrong.

- Organism-Specific: A genome belongs to a specific organism or virus (yes, even viruses have genomes, though some use RNA).

- Instructional Nature: It’s the "blueprint." It contains all the info needed to build and maintain that organism.

The study of the genome is moving fast. We’re currently looking at how "epigenetics"—the markers that sit on top of the DNA—interact with the genome. It’s like the genome is the script of a play, but the epigenome is the director telling the actors which lines to emphasize.

If you want to dive deeper into your own biology, the best first step is looking into "Whole Genome Sequencing" vs. "Genotyping." Most commercial kits (like 23andMe) only look at specific spots. True whole-genome sequencing reads all 3 billion letters. It’s more expensive, but if you want the full book rather than just the cliff notes, that’s how you get it.

Start by checking if your healthcare provider offers genomic screening, especially if you have a family history of specific conditions. Understanding your own "instruction manual" is no longer science fiction; it’s just modern medicine.