You’re probably here because you're trying to figure out which cell organelle acts like a cells solar power plant. It’s a classic biology question. Honestly, the answer is the chloroplast.

But simply naming it doesn't really do justice to how insane these little green beans actually are. Think about it. We spend billions of dollars trying to engineer efficient solar panels. Meanwhile, the clover in your backyard or the kale in your fridge is doing it silently. Effortlessly. They've been at it for billions of years.

The Green Engine: How Chloroplasts Catch Sunbeams

Plants are basically masters of making something out of nothing. Well, not nothing, but things that are essentially free: sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide. If you look at a plant cell under a microscope, you'll see these distinct green oval shapes. Those are your solar power plants.

The magic happens because of a pigment called chlorophyll.

Chlorophyll is why the world is green. It's also the "solar panel" part of the organelle. It lives inside the chloroplast, specifically within these pancake-like stacks called thylakoids. When a photon from the sun hits a chlorophyll molecule, it gets the electrons all excited. It’s a literal electrical charge.

Why we call it a solar plant

A power plant takes raw energy and converts it into a form we can use, like electricity. The chloroplast does the same thing. It takes light energy and converts it into chemical energy. That energy is stored in a sugar called glucose.

It’s pretty wild when you think about it. Every bit of food you’ve ever eaten is just "repackaged" sunlight that a chloroplast processed at some point. Even if you're eating a steak, that cow ate grass. The grass used chloroplasts. We’re all just living on solar power once removed.

👉 See also: My eye keeps twitching for days: When to ignore it and when to actually worry

The Inner Workings of the Chloroplast

If we’re going to be experts here, we have to look past the green color. A chloroplast isn't just a bag of dye. It’s highly organized.

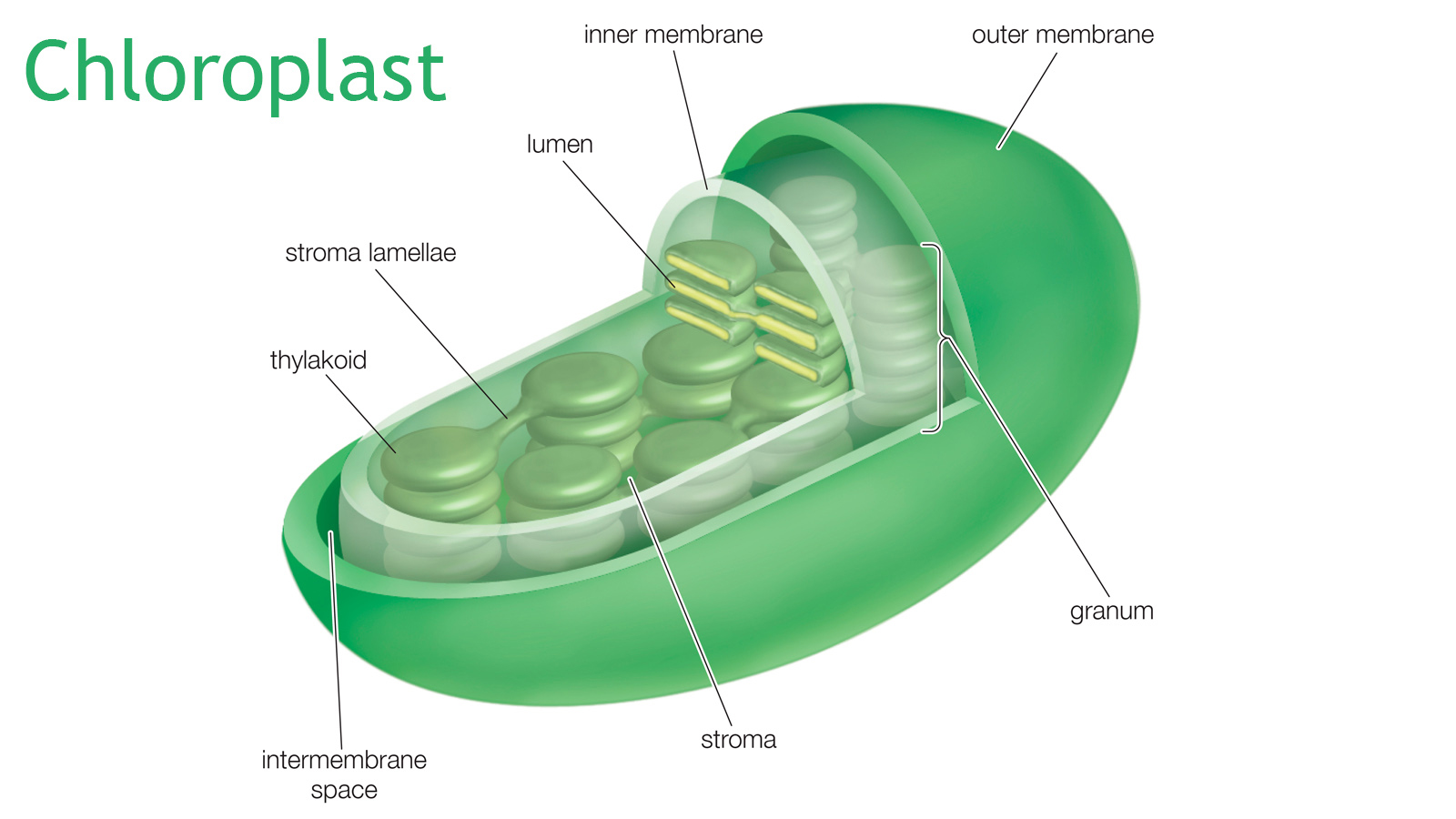

First, it has a double membrane. This is a huge deal in biology. It suggests that a long time ago—we're talking roughly 1.5 billion years—chloroplasts were actually independent bacteria. Scientists call this the Endosymbiotic Theory. Basically, a larger cell swallowed a photosynthetic bacterium, and instead of digesting it, they decided to work together.

Inside that double wall, you have the stroma. It’s a dense fluid that fills the space. Think of it like the factory floor where the final assembly happens.

Then you have the thylakoids. These are the "solar collectors." They are stacked up like coins. A stack of them is called a granum.

By stacking them, the cell maximizes the surface area. More surface area means more room for chlorophyll. More chlorophyll means more sunlight captured. It’s a masterpiece of efficiency.

The Two-Step Process: Light and Dark

The "power plant" operates in two main shifts. Biologists usually refer to these as the Light-Dependent Reactions and the Light-Independent Reactions (also known as the Calvin Cycle).

✨ Don't miss: Ingestion of hydrogen peroxide: Why a common household hack is actually dangerous

The Light-Dependent Phase: This happens in the thylakoids. Light hits the chlorophyll, water molecules are split apart, and oxygen is released as a byproduct. This is why we can breathe. The energy from the light is used to create "energy carrier" molecules called ATP and NADPH.

The Light-Independent Phase (Calvin Cycle): This happens in the stroma. The cell doesn't need "active" sunlight for this part, but it needs the energy carriers made in the first step. It takes CO2 from the air and uses that energy to build glucose.

It’s not just about sugar

While we focus on the "solar" aspect, chloroplasts do more. They are involved in synthesizing amino acids and fatty acids. They help with the plant's immune response. If a plant gets stressed by heat or drought, the chloroplasts are often the first to "signal" the rest of the cell that things are going wrong.

Common Misconceptions: Mitochondria vs. Chloroplasts

People get these two confused all the time. If the chloroplast is the solar power plant, the mitochondria is the local battery or the combustion engine.

- Chloroplasts build the fuel (glucose).

- Mitochondria burn the fuel to release energy (ATP).

Plants have both. Animals only have mitochondria. This is why we have to eat plants or other animals; we don't have the "solar panels" to make our own fuel from scratch. We are essentially energy thieves.

Why Does This Matter in 2026?

We are currently in a race to solve the climate crisis and food security issues. Scientists are looking at chloroplasts with more intensity than ever.

🔗 Read more: Why the EMS 20/20 Podcast is the Best Training You’re Not Getting in School

There is a field called Synthetic Biology where researchers like those at the Max Planck Institute are trying to create "artificial chloroplasts." If we can mimic the way a chloroplast captures carbon dioxide, we could potentially scrub CO2 from the atmosphere much more efficiently than any current mechanical "carbon capture" technology.

There's also work being done on "C4" and "CAM" photosynthesis. Some plants, like corn or cacti, have evolved slightly different ways of using their chloroplasts to survive in brutal heat. By mapping how their "solar plants" work, we might be able to genetically engineer crops that don't die during massive heatwaves.

Real-World Examples of Chloroplast Power

You can see this power in action if you've ever seen a "Variegated" leaf—one with white and green patches. The white parts lack chloroplasts. Because those areas can't produce energy, the plant usually grows slower than a solid green version. It's literally running on a smaller power grid.

Another cool example is the Elysia chlorotica, a sea slug. It eats algae and actually "steals" the chloroplasts, incorporating them into its own skin. It turns green and can survive for months just by sitting in the sun. It’s the only animal we know that effectively "runs on solar."

Actionable Insights for Biology Students and Enthusiasts

If you are studying this for an exam or just want to understand the life around you better, keep these points in mind:

- Follow the Carbon: Remember that the "goal" of the chloroplast isn't just to make energy; it’s to "fix" carbon. It takes gas (CO2) and turns it into a solid (sugar). That is a feat of engineering.

- Visualize the Tiers: Think of the leaf as the city, the cell as the factory, and the chloroplast as the specific power generator inside that factory.

- Look at the Surface: Notice how leaves are flat and wide. That’s not an accident. It’s the best shape for a solar collector.

- Observe the Seasons: When leaves turn red or yellow in the fall, you’re seeing the chloroplasts breaking down. The plant is essentially "decommissioning" its power plants for the winter to save resources.

The chloroplast is the foundation of almost all life on Earth. Without this specific organelle acting as a solar power plant, the energy from the sun would just bounce off the planet as heat. Instead, it gets captured, stored, and eventually becomes the apple you eat or the oxygen you breathe. It's the most important "green tech" in existence.

To truly understand the "solar power plant" of the cell, start by observing the plants in your own environment. Notice how they reach for the light—they are literally positioning their organelles for maximum power generation.

Next Steps for Deeper Understanding

To see this in action, you can perform a simple chromatography experiment at home. Crush a spinach leaf in a bit of rubbing alcohol and use a coffee filter to see the different pigments, including the primary "solar collector," Chlorophyll A. This allows you to physically separate the components of the cell's power plant. Additionally, researching the "Endosymbiotic Theory" will give you a fascinating look into how these organelles were once independent organisms before they became the powerhouses of the plant world.