It isn't a permanent line painted on the snow. Most people imagine a fixed boundary, something static like a border wall or a highway marker, but the reality is much weirder. If you’re asking where's the Arctic Circle, you’re actually chasing a moving target.

It shifts. Every single day.

Right now, that invisible ring sits at approximately 66°33′ North latitude. But that number is a "mean" value, a sort of mathematical compromise. Because of the way the Earth wobbles on its axis—a phenomenon scientists like Milutin Milankovitch spent lifetimes studying—the circle actually drifts north by about 15 meters every year.

The Science of the Tilt

Why does it move? Basically, the Earth isn't a perfect top. It’s more like a spinning ball that’s been kicked slightly off-center. This "axial tilt" or obliquity is currently around 23.4 degrees, but it’s slowly decreasing. As the tilt becomes less extreme, the Arctic Circle shrinks toward the North Pole.

🔗 Read more: Cheap European airline tickets: Why your search strategy is probably broken

If you stood on the line today, you’d be in one of eight countries: Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia, the United States (Alaska), Canada, Denmark (Greenland), or Iceland.

Wait. Iceland?

Actually, only a tiny sliver of Iceland—the island of Grímsey—sits on the circle. And because the line is moving north, the Arctic Circle is literally leaving Iceland behind. By around the year 2047, Grímsey will no longer be "Arctic" at all. Local residents have even installed a massive stone sphere called "Orbis et Globus" that they move every year to keep up with the shifting boundary. It's a bit of a frantic race against planetary physics.

What Happens When You Cross It?

The Arctic Circle marks the southernmost point where the sun doesn't set on the summer solstice and doesn't rise on the winter solstice. That’s the "Midnight Sun" and the "Polar Night."

It’s a bizarre experience. Imagine being in Rovaniemi, Finland, in late June. You’re sitting in a cafe at 1:00 AM, and the light is a strange, golden honey color. It’s not day, but it’s definitely not night. Your brain gets confused. Your circadian rhythm starts screaming for a dark room that doesn't exist. Honestly, it’s one of the most disorienting and beautiful things you can experience on this planet.

But don't expect a sudden change in scenery the moment you cross the line.

There isn't a wall of ice. In many places, like the Interior of Alaska or Northern Sweden, the landscape looks exactly the same for hundreds of miles in either direction. You’ll see Taiga forests—stunted spruce and pine trees—and plenty of boggy tundra. In the summer, you might even be shocked by the heat. Parts of the Arctic can hit 80°F (26°C), and the mosquitoes are legendary. They aren't just bugs; they’re a force of nature.

Finding the Circle in Real Life

If you’re trying to physically stand on the line, there are a few iconic spots to do it.

In Alaska, most people take the Dalton Highway. It’s a brutal, gravel-pelted road built for oil trucks. Around Mile 115, there’s a simple wooden sign. It’s nothing fancy. Just a place to pull over and realize how far you are from "civilization."

Norway is probably the most comfortable way to do it. You can take the Nordland Line train. There’s a specific point on the Saltfjellet mountain range where the train tracks cross the circle. They’ve built the Arctic Circle Centre there, complete with a post office where you can get a special stamp on your postcards. It’s a bit touristy, sure, but the surrounding glaciers make it feel real.

Russia has the longest stretch of the Arctic Circle, but it's arguably the hardest to visit for most travelers right now. Cities like Murmansk—the largest city north of the circle—offer a glimpse into how millions of people actually live and work in the deep cold. It's not all dog sleds and igloos; it’s brutalist architecture, shipping ports, and nuclear icebreakers.

Common Misconceptions About the North

A lot of people think the Arctic Circle is the same thing as the "Tree Line."

It’s not.

The tree line—the point where it’s too cold or the soil is too frozen for trees to grow—is much more erratic. In some places, the tree line is hundreds of miles south of the Arctic Circle. In others, trees grow well north of it. Ecology doesn't care about our neat little lines of latitude.

Another big one: "It's always freezing."

Nope. While the winter is obviously harsh, the Arctic is experiencing "Arctic Amplification." The region is warming nearly four times faster than the rest of the globe. This isn't just a statistic; it's changing where the Arctic Circle "feels" like the Arctic. Permafrost is thawing under towns like Utqiaġvik (formerly Barrow), Alaska, causing roads to buckle and houses to sink.

The Geography of the Arctic Circle

When you're looking at a map, the circle is roughly 1,650 miles south of the North Pole.

But if you want to be precise about where's the Arctic Circle, you have to look at the specific coordinates that change with the seasons. The nutation of the Earth—a small "nodding" motion—means the circle can jump back and forth by several meters over a few days.

- North America: The line cuts through the Yukon and Northwest Territories in Canada. It’s incredibly remote.

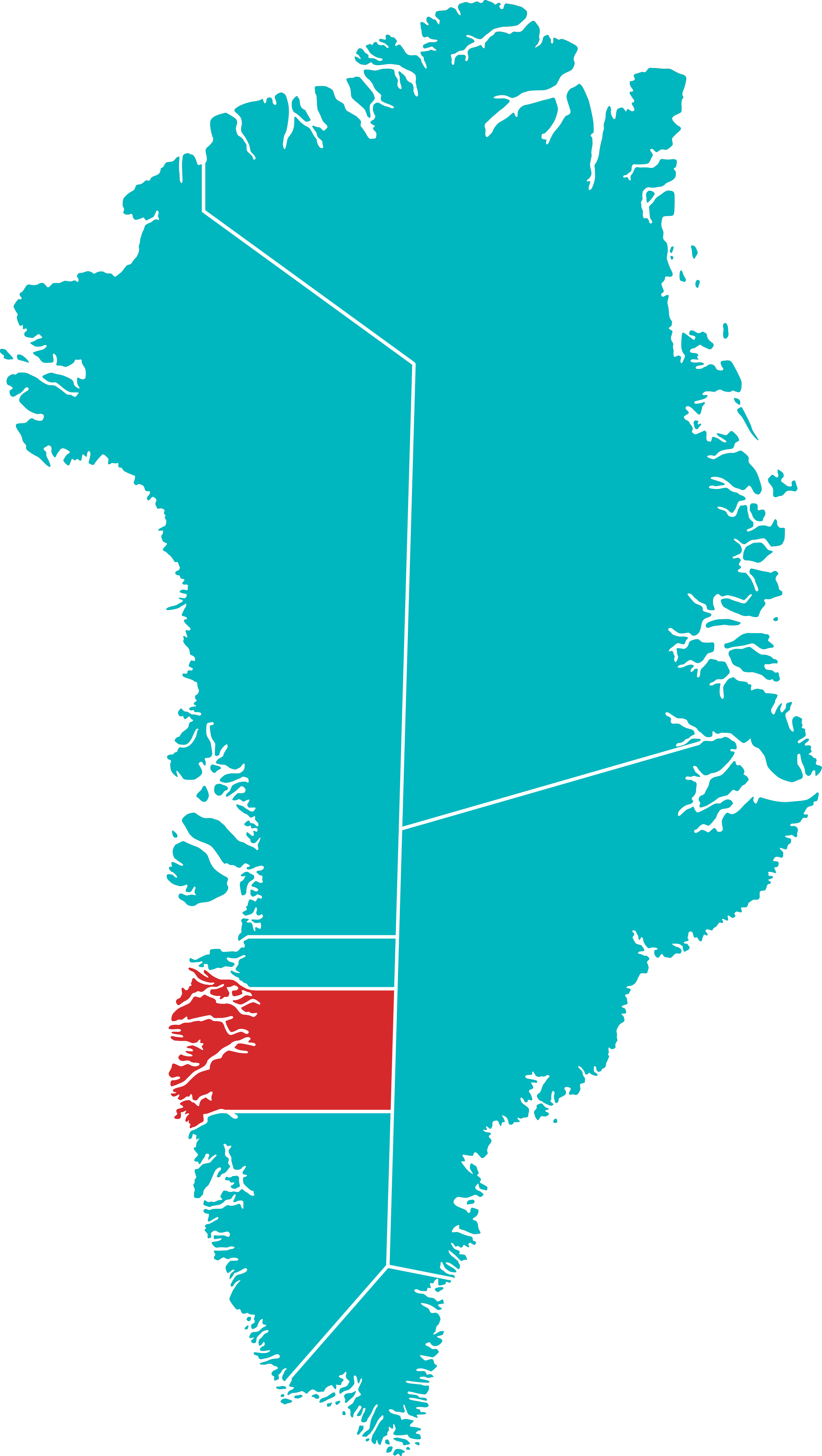

- Greenland: Most of this massive island is inside the circle. It’s basically the "heart" of the Arctic.

- Scandinavia: This is the most accessible part. You can literally drive a rental car across the circle in Finland.

- Asia/Russia: It spans thousands of miles across Siberia, mostly through uninhabited or industrial wilderness.

Why Does This Line Even Exist?

It’s all about the sun.

The Greeks were actually some of the first to figure this out. The word "Arctic" comes from the Greek word Arktos, meaning "bear." This refers to the Great Bear constellation (Ursa Major), which stays high in the northern sky. They realized there was a point on the globe where the stars behaved differently and the sun stayed up longer.

For modern science, the circle is a vital boundary for studying climate. It’s the frontier of the "cryosphere"—the frozen parts of our world. Scientists use the circle to define regions for wildlife protection, particularly for migratory birds and the roughly 25,000 polar bears that call the high north home.

Planning Your Trip to the Line

If you’re serious about visiting, don't just go for the "line." Go for the environment.

The best time to visit depends entirely on what you want to see. If you want the Midnight Sun, go between June 12th and July 1st. If you want the Northern Lights (Aurora Borealis), you actually want to go when it's dark—late September to March.

Pro tip: You don’t have to be inside the Arctic Circle to see the Northern Lights. In fact, the "auroral oval" often sits just south of the circle. Places like Fairbanks, Alaska, or Tromsø, Norway, are prime viewing spots even though they are right on the edge.

✨ Don't miss: Secaucus Junction to New York Penn Station: How to Actually Navigate This Mess Without Stress

Actionable Steps for the Arctic Bound

- Check the current drift: Use sites like the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS) if you’re a total geography nerd and want the exact coordinate for your GPS.

- Pick your gateway: Rovaniemi (Finland) is best for families. Tromsø (Norway) is best for scenery and cruises. Fairbanks (USA) is best for rugged road trips.

- Pack for "The Layering Rule": Even in summer, the wind off the Arctic Ocean can drop temperatures to 40°F (4°C) in minutes. Wool base layers are your best friend.

- Respect the Permafrost: If you're hiking, stay on marked trails. The tundra is incredibly fragile; a single footprint can last for decades because the plants grow so slowly.

The Arctic Circle isn't just a coordinate. It's the gateway to a part of the world that operates on a different clock. It’s where the sun forgets to sleep and the Earth shows its age. Whether you find it via a dusty road in Alaska or a luxury train in Sweden, crossing that 66°33′ North mark is a reminder of how massive and beautifully unstable our planet really is.