It’s easy to miss. If you’re driving down Route 1 in Pennsylvania, south of West Chester, you’re basically flying through one of the bloodiest, most chaotic afternoons in American history. People always ask, where was the Battle of Brandywine, expecting a single field with a fence around it. It isn't like that. Not even close.

This wasn't a skirmish. It was a massive, sprawling disaster for the Continental Army that stretched across ten square miles of rolling hills, thick woods, and treacherous river crossings.

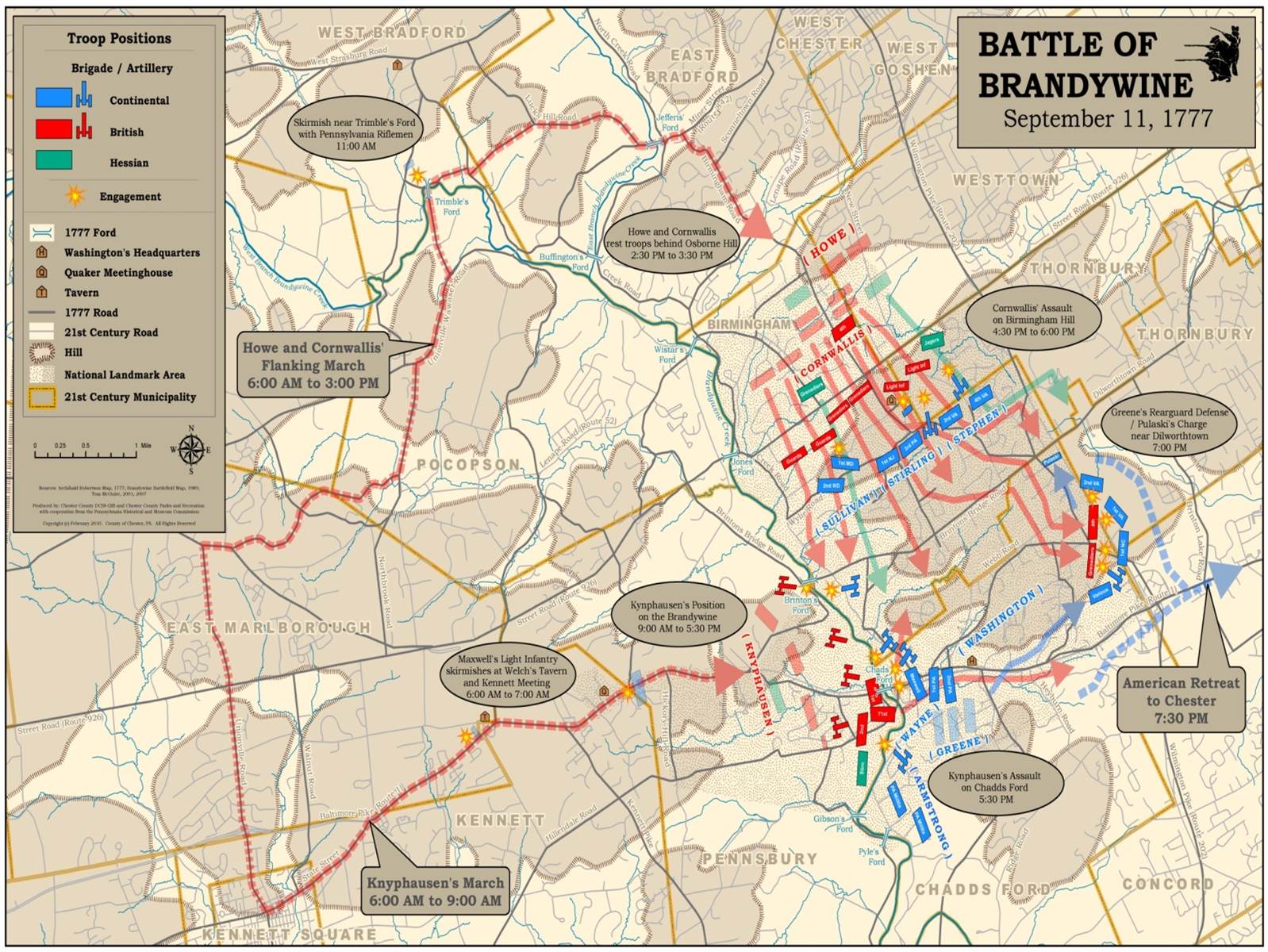

September 11, 1777. That’s the date. While we think of it as a historical marker now, for George Washington, it was the day his intelligence failed and his flank got turned. He thought he was guarding a few specific river fords. He was wrong. The British, led by Sir William Howe, pulled off a move that would make a chess grandmaster sweat. They marched 17 miles in the heat, circled around the American right, and suddenly, the war was nearly over before it really began.

The Epicenter: Chadds Ford and the Brandywine River

Basically, the heart of the action sits in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. This is the literal answer to "where was the Battle of Brandywine." It’s located in Delaware County, but the fighting spilled heavily into Chester County too. If you stand near the Brandywine River Museum of Art today, you’re standing where the American center was braced for impact.

Washington had his guys lined up along the high ground on the east bank of the Brandywine River. He was watching the "fords"—those shallow spots where an army can actually cross without drowning their horses or soaking their gunpowder. He focused on Chad’s Ford (the spelling has changed over time) because it was the most direct route for the British to get to Philadelphia.

The Brandywine itself isn't some massive, crashing waterway. It’s a winding, scenic river. But back then, with heavy rains and dense brush, it was a formidable barrier. Washington’s men dug in, staring across the water, waiting for a fight that was actually happening five miles to their north.

The Great Flanking Maneuver: Birmingham Hill

If you want to see where the battle was actually lost, you have to leave the river and head to Birmingham Friends Meeting House. Honestly, this is the most eerie part of the whole battlefield.

While the Hessian troops (the German mercenaries hired by the British) were making a lot of noise and smoke down at Chadds Ford to keep Washington’s eyes glued to the river, Howe and Cornwallis were taking the long way around. They crossed way up at Trimble’s Ford and Jefferis’ Ford.

By the time Washington realized he’d been tricked, the British were cresting the hills near the Quaker meeting house.

The Quakers were inside having a meeting. They were pacifists. They literally sat there in silence while the British army formed up in their backyard. Think about that for a second. You're sitting in a wooden pew, trying to find inner peace, and 10,000 professional soldiers are fixing bayonets outside your window.

The fighting at Birmingham Hill was savage. It wasn't organized lines like you see in movies. It was "hedgerow fighting"—bloody, close-quarters stuff. The Americans, under General Sullivan, tried to pivot and form a line, but they were scrambled. The Quaker cemetery walls became a breastwork. Blood literally ran down the aisles of the meeting house later that night when it was turned into a field hospital.

Exploring the Brandywine Battlefield Park

You can’t just look at a map; you’ve got to feel the elevation. The Brandywine Battlefield Park is the primary state-run site, located on Route 1. It’s about 50 acres, which sounds like a lot, but remember: the battle covered 10,000 acres.

- The Ring House: This was Washington’s headquarters. It’s a sturdy stone building where he likely paced the floor while receiving conflicting reports about where the British actually were.

- The Gilpin House: This is where the Marquis de Lafayette stayed. The young Frenchman was just 19 years old and looking to prove himself. He ended up taking a musket ball to the leg during the retreat. He became a hero that day, not for winning, but for helping keep the retreat from becoming a total massacre.

- The Museum: They’ve got a solid collection of artifacts—buttons, lead balls, personal items found in the dirt. It gives you a sense of the scale.

But here’s the thing: most of the battlefield is now private property or suburban neighborhoods. People in Chadds Ford literally have the Battle of Brandywine in their backyards. You'll be driving past a Starbucks or a high-end furniture store, and you’re actually driving over the spot where the 1st Maryland Regiment tried to hold back a wave of British Grenadiers.

Why the Location Mattered: The Road to Philly

Why here? Why this specific spot in Pennsylvania?

The British had sailed from New York, went down the coast, and came up the Chesapeake Bay. They landed at "Head of Elk" (now Elkton, Maryland). Their goal was Philadelphia, the rebel capital.

Washington had to stop them. The Brandywine River was the last natural defensive line before the city. If the British crossed the Brandywine, Philadelphia was a goner. And they did cross. And Philadelphia did fall.

But the terrain—the thick woods and the steep hills—actually saved the American army. Even though they lost the ground, the broken landscape allowed the Continental soldiers to melt away into the forest rather than being captured en masse. They lost the battle, but they didn't lose the war.

Key Landmarks You Can Still Visit Today

If you’re planning a trip to see where was the Battle of Brandywine, don't just stick to the visitor center. You need to do a driving tour. The landscape hasn't changed as much as you’d think in some spots.

- Sanderson Museum: Chris Sanderson was a local who spent his life collecting "relics" from the fields. It’s a quirky, very "human" look at the history that the big state museums sometimes miss.

- Dilworthtown Inn: This area saw intense fighting during the final retreat as the sun was going down. The British eventually took the inn and used it as a headquarters.

- Osborne's Hill: This is where General Howe stood to watch his troops sweep down onto the Americans. From here, you can see exactly why the American position was so vulnerable once the British got behind them.

- Squire Cheyney’s Farm: Squire Thomas Cheyney is a local legend. He was the one who rode his horse to exhaustion to tell Washington, "The British are coming from the north!" Washington didn't believe him at first. Cheyney allegedly got so frustrated he told the General, "If you doubt my word, put me under guard until you can ask someone else!"

Common Misconceptions About the Location

A lot of people think the battle happened at a fort. There was no fort. "Chadds Ford" is a name, not a fortification. This was a battle of movement.

Another mistake? Thinking it was a small engagement. This was the largest single-day battle of the entire American Revolution in terms of the number of troops engaged. Nearly 30,000 soldiers were moving through these woods.

And don't assume it's all "national park" land. Unlike Gettysburg, which is a massive protected park, Brandywine is a patchwork. You have to be respectful. Much of the ground where men died is now someone’s driveway or a quiet horse pasture.

How to Experience the Battlefield Today

If you want to really understand the geography, start at the Brandywine Battlefield Park visitor center for the context. Then, grab a map of the "flanking march."

Follow the route the British took. Drive north to the forks of the Brandywine. See how narrow the roads are. Imagine thousands of men in heavy wool uniforms marching in 90-degree heat through that dust.

Then, head to the Birmingham Friends Meeting House. Stand in the cemetery. Look south toward the river. You can see the "undulations" in the ground—the little dips and rises—that soldiers used for cover. It's incredibly quiet there now, which makes the history feel even heavier.

Actionable Steps for Your Visit:

- Download a GPS-enabled battle map: Apps like the American Battlefield Trust’s "Battle of Brandywine" tour are lifesavers because the signage on the actual roads can be sparse.

- Check the Meeting House hours: If you want to see the bloodstains on the floorboards (yes, they are still there), you need to check when the Quakers allow visitors inside.

- Visit in the Fall: If you go in September, the light and the foliage are almost exactly what the soldiers would have seen. It’s a hauntingly beautiful experience.

- Wear hiking boots: If you plan on walking the trails near the river, it gets muddy. The "ford" areas are still quite wild.

The Battle of Brandywine wasn't just a location on a map. It was a failure of intelligence, a masterclass in maneuvering, and a testament to the grit of soldiers who were outmatched but refused to quit. To see it, you have to look past the modern suburbs and see the bones of the land. The hills are still there. The river still flows. And the story is written in the dirt of Chadds Ford.