You’ve probably seen the iconic image of a massive bull standing against a snowy Yellowstone backdrop. It’s the quintessential American scene. But if you look at a historical american bison range map compared to one from today, the difference is honestly staggering. It’s not just a "small change." It is a near-total erasure of a species that once dictated the ecology of an entire continent.

Imagine a blanket. A thick, furry, brown blanket covering almost everything from the Great Slave Lake in Canada down into the golden grasslands of Mexico. That was the reality.

Thirty million animals. Maybe sixty million.

📖 Related: Does Iceland Use the Euro? What Most People Get Wrong

Historians and biologists like Dan Flores have spent decades trying to piece together exactly how far these animals roamed. It wasn't just the Great Plains. People often forget that. Bison were in the forests of the East and the high mountain valleys of the West. If you walked through Kentucky in 1750, you weren't just seeing deer; you were seeing bison.

The Massive Reach of the Original American Bison Range Map

Most people think "bison" and they think "Kansas." Or maybe "South Dakota."

While the shortgrass prairies were the heart of their world, the original american bison range map actually touched the Atlantic coast in places. They were in Georgia. They were in New York. There’s a reason why there’s a city called Buffalo in New York, even if some historians argue over the exact naming origin. The "Wood Bison" subspecies pushed far north into Alaska and the Yukon, while the "Plains Bison" dominated the mid-section of the continent.

They were engineers.

Their hooves broke up the soil, creating "wallows" that filled with rainwater. These little ponds became tiny ecosystems for frogs and shorebirds. By grazing, they kept the grasses healthy, which in turn supported prairie dogs, which then supported ferrets and hawks. It was a massive, humming machine of biology. When you look at a map of their old territory, you’re basically looking at a map of the most fertile, productive land in North America.

The Great Contraction: How the Map Shrank to Nothing

Then came the 1800s.

It wasn't a slow decline. It was a cliff. By the late 1880s, that massive map that once covered two-thirds of the continent had shrunk to a few tiny, pathetic dots. Some experts estimate there were fewer than 1,000 bison left in the entire world.

It was a combination of things. You had commercial hunting for hides. You had the expansion of the railroads. Most tragically, you had a deliberate government policy to starve out Indigenous nations by removing their primary food source. General Philip Sheridan famously remarked that hunters were doing more to "settle the Indian question" than the entire regular army.

By 1884, the wild herds were basically gone.

The american bison range map at that moment in history is just depressing. A handful of animals in Yellowstone. A few on private ranches, like the one owned by Charles Goodnight in Texas or the Scotty Philip herd in South Dakota. That’s it. That was the thread by which the species hung.

Where Can You Actually See Them Now?

If you look at a modern american bison range map, you’ll see it’s a patchwork. It looks like a starry sky—lots of little pinpricks of conservation herds spread across the country.

Yellowstone National Park: The Genetic Gold Standard

This is the big one. It’s the only place in the U.S. where bison have lived continuously since prehistoric times. They never went extinct here. Because of that, the Yellowstone herd is incredibly important for genetics. They haven't been "cattle-crossed," which happened to many other herds during the lean years of the early 20th century.

The Badlands and Wind Cave

South Dakota is essentially the modern stronghold for the species. At Wind Cave National Park, the bison are descendants of the original New York Zoological Society animals that were sent west to repopulate the plains. It’s a full-circle story.

Private Ranches and the "Buffalo Commons"

Interestingly, the majority of bison today aren't in National Parks. They are on private land. Ted Turner, for instance, owns massive swaths of land across the West and maintains thousands of head. While these are managed more like livestock than wild wildlife, they are a crucial part of the species' footprint.

💡 You might also like: Hotel Madrid Gran Via 25 Affiliated by Meliá: Why This Spot Actually Lives Up to the Hype

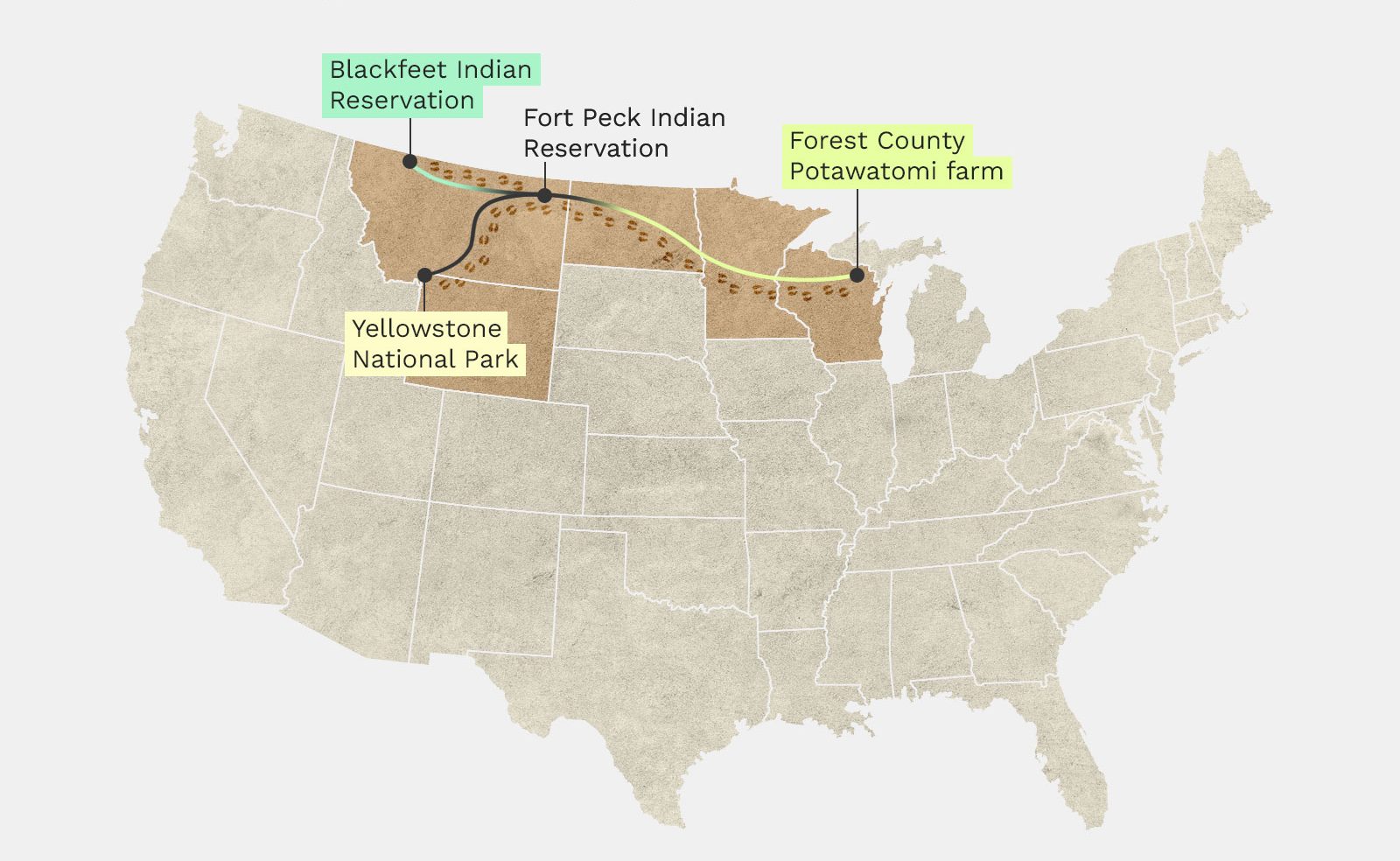

Tribal Lands and the InterTribal Buffalo Council

This is arguably the most exciting part of the modern map. Indigenous nations are leading the charge in restoration. The InterTribal Buffalo Council (ITBC) represents over 80 tribes across 20 states. They are moving bison back to ancestral lands, from the Blackfeet Nation in Montana to the Osage in Oklahoma. This isn't just about biology; it’s about cultural healing.

Understanding the "Modern" Range vs. "Historic" Range

We have to be honest here. A modern american bison range map is a bit of a lie.

True "wild" bison—animals that can migrate hundreds of miles according to the seasons—don't really exist in the lower 48 anymore. Most herds are behind fences. Even in Yellowstone, if the bison try to leave the park to follow their old migratory paths into Montana, they are often hazed back or killed due to concerns about brucellosis, a disease that cattle ranchers fear (despite very little evidence of actual transmission from bison to cows in the wild).

The map we see today is a map of islands.

Conservationists are trying to build bridges between these islands. There’s a concept called the "American Prairie" in Montana that aims to connect fragmented pieces of land into a massive, three-million-acre reserve. If they succeed, the american bison range map might actually start to look like a cohesive territory again rather than a scattered collection of zoos.

The Surprising Places Bison Still Roam

You might not expect to find bison in the middle of a swamp.

But down in Florida, at Payne’s Prairie Preserve State Park, there is a small herd. They were introduced in the 1970s to recreate what the landscape looked like when William Bartram visited in the 1700s. Yes, Florida had bison.

Likewise, the Catalina Island bison in California are a weird anomaly. They were brought there for a movie in the 1920s and just... stayed. They aren't native to the island, and they’ve caused some ecological headaches, but they are a fascinatng footnote on the modern map.

Why Genomes Matter for the Map

When you look at a map of where bison are "allowed" to be, you also have to look at what's inside the bison.

- Cattle Gene Introgression: Many "bison" in the U.S. carry small amounts of domestic cattle DNA.

- Pure Herds: Places like Wind Cave, Yellowstone, and Elk Island in Canada are some of the few spots with "pure" bison.

- The Wood Bison: Don't forget the North. The Wood Bison (Bison bison athabascae) are larger and live in the boreal forests. Their range map is expanding in Alaska and Canada thanks to aggressive reintroduction programs.

Future Projections: Will the Map Ever Grow?

The dream is a "Buffalo Commons."

This idea, proposed by Frank and Deborah Popper in the late 80s, suggested that parts of the Great Plains where the human population is thinning out should be returned to a massive, open-range bison commons. People hated the idea at the time. Now? It’s starting to look like a prophecy.

As water becomes scarcer and cattle ranching becomes harder in the arid West, bison make more sense. They handle the heat better. They handle the cold better. They don't need to be pampered.

Actionable Steps for Enthusiasts and Travelers

If you want to see the american bison range map in person, don't just go to the gift shop.

- Check the "Status" of the Herd: Before you visit a park, look up if it's a "conservation herd" or a "commercial herd." It changes the experience.

- Visit Tribal Lands: Support tribal tourism. Places like the Wolakota Buffalo Range in South Dakota are doing some of the most important conservation work on the planet.

- Download Range Apps: Use apps like iNaturalist or specific park maps to see where sightings are common.

- Volunteer for Restoration: Organizations like the American Prairie or the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) have active programs to expand the bison's footprint. They often need help with fence removal—one of the biggest obstacles to a truly wild range map.

- Look for "Bison Bridges": Keep an eye on wildlife crossing projects. The more bridges we build over highways, the more that "island" map can start to connect.

The story of the bison is the story of America. It’s a story of greed, nearly total destruction, and a very slow, very hard-fought comeback. The map isn't as big as it used to be. It might never be. But every time a new herd is released onto tribal land or a new conservation easement is signed, that map grows a little bit more. It's a map of hope, really.

To truly understand the bison, you have to look at the gaps in the map. Those gaps are where the work still needs to be done. We are currently in the middle of a multi-generational project to stitch those pieces back together. It’s not just about the animal; it’s about the grass, the soil, and the people who live alongside them.