It is exactly ten sentences long. Ten. That is the entire textual backbone of Maurice Sendak’s 1963 masterpiece. Most people don’t realize how thin the script actually is because the illustrations do all the heavy lifting, screaming from the page with those cross-hatched claws and yellow eyes. If you grew up with Where the Wild Things Are, you probably remember the smell of the library paper or the way Max’s wolf suit looked a little too itchy. But honestly, the book almost didn't happen. At least, not with monsters.

Originally, Sendak wanted to call it Where the Wild Horses Are. The problem? He couldn't draw horses. He told his editor, Ursula Nordstrom, that he could draw "things," and those things ended up being caricatures of his grotesque, loud, and eccentric Brooklyn relatives. It’s a hilarious bit of history. Imagine being one of his aunts or uncles, opening a book, and seeing your own nose on a monster with scales.

The Controversy That Nearly Killed a Classic

When Where the Wild Things Are first hit shelves, the "experts" absolutely hated it. It’s hard to imagine now, but child psychologists in the sixties were convinced the book was psychologically damaging. They thought it was too dark. Too scary. They feared it would traumatize children by showing a mother sending her child to bed without supper—a move that was considered "cruel" in the pedagogical literature of the time.

Bruno Bettelheim, a prominent (though later controversial) child psychologist, famously slammed the book in Ladies’ Home Journal. He hadn't even read it. He just knew it was dangerous. He argued that it was "too frightening" for young kids to handle the idea of a mother withholding food. But here’s the thing: kids loved it. They didn't see a trauma; they saw themselves. They saw Max, a kid who was absolutely fed up with being told what to do, found a way to become the king of his own chaos, and then—this is the important part—decided he’d rather be loved than be in charge.

Why the Art Style Feels So Different

Have you ever looked really closely at the lines in the book? Sendak used a technique called cross-hatching. It’s tedious. It’s thousands of tiny, intersecting lines that create depth and shadow. Most modern picture books use flat vectors or soft watercolors, but Where the Wild Things Are feels "crunchy" and tactile.

✨ Don't miss: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

The layout of the book is a psychological trick, too. Look at the margins. When Max is in his bedroom, the white borders are huge. He's trapped. As his imagination takes over and the forest grows, the white space disappears. By the time the "Wild Rumpus" starts, the illustrations have literally pushed the words off the page. The art takes over completely. There are three full spreads with zero text. Just pure, unadulterated noise in visual form. Then, as Max starts to miss home, the white borders creep back in. It’s a visual heartbeat.

The Real Max and the Wolf Suit

Max isn't a "good" kid in the traditional 1950s sense. He’s a terror. He chases the dog with a fork. He yells at his mom. Sendak was one of the first creators to acknowledge that childhood isn't just sunshine and lemonade; it’s full of rage, boredom, and a desperate need for control.

Max’s wolf suit is his armor. It’s his permission to be "wild."

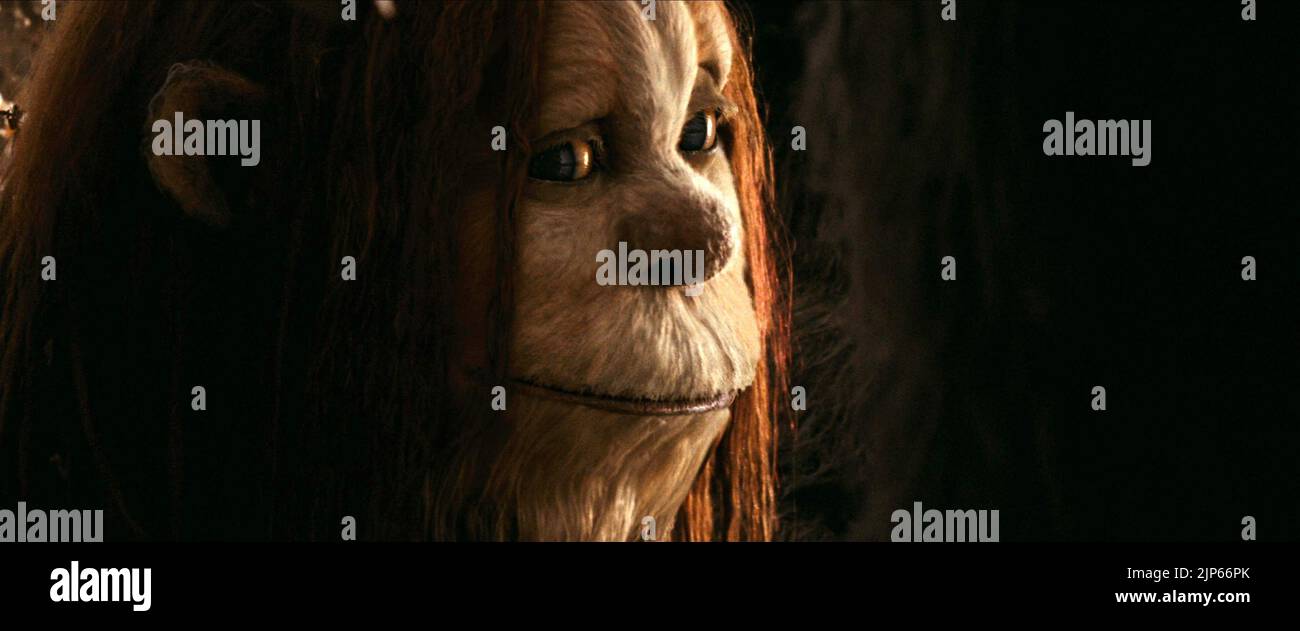

Interestingly, Spike Jonze’s 2009 film adaptation took this even further. While the book is a lean 338 words, the movie is a sprawling, melancholic look at divorce and emotional regulation. Some fans of the book hated the movie because it felt too sad, but Sendak actually loved it. He told Jonze not to make a "safe" movie. He wanted it to feel as dangerous as being a real nine-year-old feels.

🔗 Read more: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

The Cultural Legacy and the Caldecott Win

Despite the early pearl-clutching by librarians, the book won the Caldecott Medal in 1964. It’s basically the Oscar for picture books. During his acceptance speech, Sendak didn't hold back. He talked about how children are complex beings who live with "the constant fluctuation of their own emotions."

He knew that "taming" the monsters wasn't about making them go away. It was about Max realizing that being the King of the Wild Things is actually pretty lonely. You can’t eat the people you love, even if you love them "so."

- Fact Check: The "Wild Things" don't actually have names in the book.

- Fact Check: The 2009 film gave them names like Carol, K.W., and Alexander.

- Fact Check: Sendak’s own childhood was overshadowed by the Holocaust; many of his family members were killed, and he often said the "Wild Things" represented the chaos of the world he couldn't control as a child.

Why We Are Still Talking About It in 2026

Honestly, the book stays relevant because it doesn't talk down to anyone. It’s a story about a kid having a tantrum and finding his way back to the dinner table. It’s about the fact that "hot" food is a universal symbol for "you are forgiven."

We live in an era of hyper-sanitized children’s media. Everything is bright, loud, and educational. Where the Wild Things Are is none of those things. It’s dark, quiet, and a little bit weird. It suggests that it's okay to be angry. It suggests that imagination is a place you go to process the stuff you can't say out loud to your parents.

💡 You might also like: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

Real-World Takeaways for Parents and Readers

If you're revisiting the book or introducing it to a new generation, keep a few things in mind. First, don't rush the "Wild Rumpus" pages. Let the kid look at the monsters' feet—they're weirdly human, which is intentional. Second, talk about the "supper." The fact that it was "still hot" is the most important line in the book. It means no time has passed. It means Max was safe the whole time.

If you want to dive deeper into the world of Sendak, look for the "Trilogy." Sendak considered this book the first in a loose trilogy, followed by In the Night Kitchen and Outside Over There. They all deal with the same theme: children navigating a world that is much bigger and scarier than they are.

Next Steps for the Sendak Enthusiast:

- Track down a first edition: If you can find one (and have a few thousand dollars), look for the specific shade of pink on the monsters' scales—it changed in later printings.

- Watch the 1973 animated short: It’s narrated by Peter Schickele and has a very different, almost jazzy vibe compared to the Jonze film.

- Read Sendak’s final interview: His 2011 interview with Terry Gross on Fresh Air is heartbreaking and beautiful. He talks about the end of life with the same blunt honesty he used to talk about childhood.

- Check out the "Rosenbach Museum": They house most of Sendak’s original drawings and manuscripts in Philadelphia. It’s a pilgrimage site for anyone who cares about the history of the "Wild Things."

The magic of Max's journey isn't that he went away. It's that he came back. He realized that a room with a warm meal is better than a kingdom of monsters, even if those monsters really do love you.

---