You know the song. You’ve definitely heard that "Pass the Dutchie" bassline at a wedding, a backyard BBQ, or maybe just in a random Netflix sync. It’s infectious. But there’s a weirdly dark, or at least bittersweet, reality behind the five faces you saw grinning on Top of the Pops back in 1982. The members of Musical Youth weren't just some manufactured boy band; they were kids from Birmingham, England, who got swept up in a whirlwind that, quite frankly, they weren't prepared for.

Most people think they just vanished. They didn't.

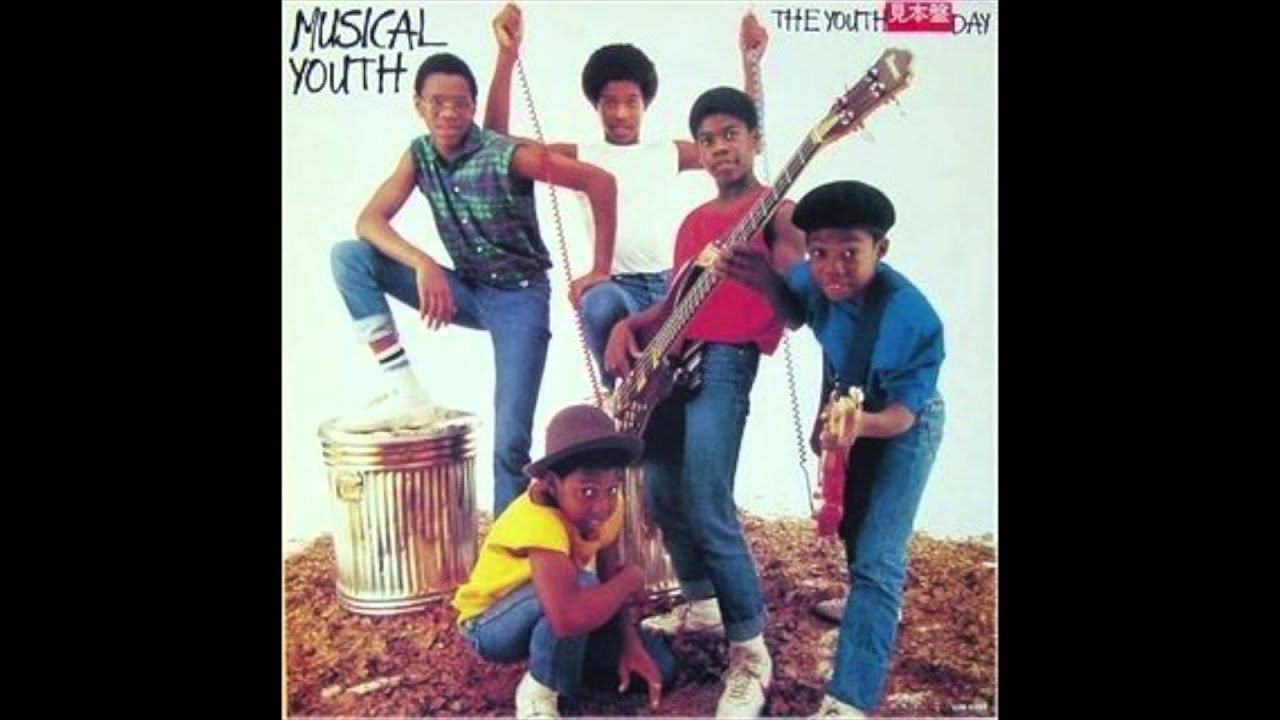

The group was built around two sets of brothers: the Waite brothers and the Grant brothers. You had Patrick Waite on bass and Freddie Waite on drums. Then there was Kelvin Grant and Michael Grant. Adding a little extra flavor to the mix was the lead singer, Dennis Seaton. When they hit it big, they were incredibly young. We’re talking 11 to 15 years old. Imagine being 12 and getting a Grammy nomination. It's wild. It’s also a recipe for a very complicated adulthood.

The original lineup and the Birmingham roots

Musical Youth didn't just fall out of the sky. They were a product of the vibrant West Midlands reggae scene. Birmingham in the late 70s and early 80s was a melting pot. You had Steel Pulse, The Beat, and UB40 all emerging from the same concrete landscape. The members of Musical Youth were actually formed by the fathers of the Grant and Waite boys. Frederick Waite Sr. was a former member of the Jamaican vocal group The Techniques. He knew the business—or at least, he thought he did.

Initially, the band featured Frederick Sr. on lead vocals. However, they soon realized that the real "hook" was the kids. They brought in Dennis Seaton, and that was the spark. They signed to MCA Records, and suddenly, these schoolboys were flying to 15 countries in as many days.

Dennis Seaton: The Voice

Dennis was the focal point. He had that clean, melodic tone that made reggae palatable for the BBC Radio 1 crowd without stripping away the genre's soul. When the band splintered in 1985, Dennis was the first to try the solo route. He formed a group called XMY, but it never really caught fire. Honestly, the industry is brutal to former child stars. You're frozen in time as a 14-year-old in the public's mind. For years, Dennis worked outside the lime-light, even spending time as a delivery driver and in various regular-guy jobs while still keeping his hand in the music scene.

💡 You might also like: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

Michael and Kelvin Grant: The Melodic Core

Michael Grant (keyboards) and Kelvin Grant (guitar) were the other half of the creative engine. After the band's initial 1985 breakup, they largely stayed out of the mainstream tabloid eye, which was probably a smart move. Kelvin continued to release solo material, though it mostly circulated within the reggae community rather than the Billboard charts. Michael, meanwhile, focused on the production side and stayed involved in the Birmingham music infrastructure.

The tragedy of Patrick Waite

If you want to understand why Musical Youth isn't just a happy nostalgia trip, you have to talk about Patrick Waite. He was the bassist. He was also the first to really suffer the consequences of the "too much, too soon" lifestyle. By the early 90s, the money was gone. The hits had dried up. Patrick fell into a spiral of petty crime and drug use.

It’s heartbreaking.

In 1993, while awaiting a court appearance, Patrick collapsed and died at his mother's home. He was only 24. It was a hereditary heart condition—myocarditis—but many feel the stress of his post-fame life played a role. His death effectively ended any hope of a full "classic" lineup reunion. You can't replace that chemistry.

Freddie Waite’s quiet struggles

Freddie, Patrick’s brother and the drummer, also faced significant mental health challenges after the band dissolved. The transition from being an international superstar to a regular citizen in Birmingham is a massive psychological shock. Freddie spent significant time away from the public eye, dealing with his own battles. It’s a recurring theme with the members of Musical Youth: the industry took the best years of their childhood and left them to figure out the rest of their lives on their own.

📖 Related: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

The 2001 comeback and the legal battles

In 2001, interest in 80s nostalgia started peaking. Dennis Seaton and Michael Grant decided to reform Musical Youth as a duo. They’ve been touring ever since. You can still catch them at festivals like Bestival or various "80s Rewind" shows. They sound good. Dennis still has the pipes.

But it wasn't all smooth sailing.

There have been long-standing disputes regarding royalties. This is the part people forget: because they were minors when they signed their contracts, the legalities were messy. They famously sued their former lawyers in the mid-2000s, claiming they lost out on millions because of poor advice and predatory deals. It's the classic "Behind the Music" story, but it’s their actual lives. They were kids who sold millions of records and ended up with very little to show for it financially for a long time.

Why they still matter today

You might think of them as a footnote, but Musical Youth were pioneers. They were the first black act to be played in heavy rotation on MTV. Think about that. Before Michael Jackson's "Billie Jean" broke the color barrier on the network, these kids from Birmingham were on screen. They paved the way for the globalization of reggae-pop.

- Cultural Impact: They made reggae accessible to a global "pop" audience without the heavy political overtones of roots reggae.

- Representation: For a generation of black British kids, seeing people who looked like them on Top of the Pops was massive.

- The "Dutchie" Legacy: The song itself is a cover/interpolation of The Mighty Diamonds' "Pass the Kutchie." The kids changed "Kutchie" (pot pipe) to "Dutchie" (cooking pot) to make it radio-friendly. It was a stroke of marketing genius that probably saved their careers before they even started.

What to do if you're a fan now

If you’re looking to support the remaining members of Musical Youth, don't just stream the hits. The streaming payouts for legacy acts are notoriously tiny.

👉 See also: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

Check out their more recent live performances. Michael and Dennis are still active and they put on a high-energy show that honors the original spirit of the band. They released a "reggae anthology" style project a few years back where they covered classic reggae tracks that influenced them. It’s worth a listen if you want to see them as musicians rather than just museum pieces.

Also, look into the solo work of Kelvin Grant. He’s kept the roots-reggae fire burning in a way that’s very different from the pop-sheen of the 82-83 era.

Ultimately, the story of Musical Youth is a cautionary tale about the music industry, but it's also a story of resilience. Dennis and Michael didn't let the tragedies of the past keep them from the stage. They’ve reclaimed their legacy. They aren't just "those kids" anymore; they are the elder statesmen of a very specific, very influential era of British music.

If you want to dive deeper, look for the documentary footage of their early tours in Jamaica. Seeing the contrast between their Birmingham upbringing and their "homecoming" in Kingston tells you everything you need to know about their identity. They were caught between two worlds, and they managed to create a sound that belonged to both.

Next Steps for the Music Fan:

- Listen to 'The Youth of Today': Move beyond the lead single. The whole album is a masterclass in early 80s production.

- Support Live Music: Check the official Musical Youth social channels for UK festival dates; they are frequent fixtures on the summer circuit.

- Research the 'Birmingham Sound': Look up The Beat and Steel Pulse to understand the environment that birthed the band.

The members of Musical Youth deserve more than being a trivia question. They lived the highest highs and some pretty devastating lows, and the fact that they're still making music today is a win in itself.