If you zoom in on a standard map of South America Falkland Islands usually appear as two jagged green specks sitting roughly 300 miles off the Patagonian coast. They look small. Isolated. Almost like an afterthought compared to the massive curve of the Andes or the sprawl of the Amazon. But those tiny dots carry a weight that honestly defies their size. Maps aren't just about geography; they’re about who owns the story. Depending on where you buy your map, those islands might be labeled the "Falkland Islands (UK)" or "Islas Malvinas (Argentina)."

It's a cartographic headache that has lasted centuries.

Most people looking at a South American map just want to know how to get there or where the penguins are. Fair enough. But you can't really understand the region without realizing that these islands are the center of a tug-of-war that involves international law, 18th-century colonial claims, and a very real war that happened in 1982. When you look at the physical coordinates—roughly $51^{\circ}S, 59^{\circ}W$—you see a sub-antarctic archipelago. What you don't see is the thicket of political tension that makes this specific spot on the map so unique.

The Geography of the Map of South America Falkland Islands

Geologically, the islands are part of the South American continental shelf. That's a huge point for Argentina. They argue that because the islands sit on the same underwater plateau as the mainland, they are naturally part of the continent. It's a "proximity is destiny" kind of argument.

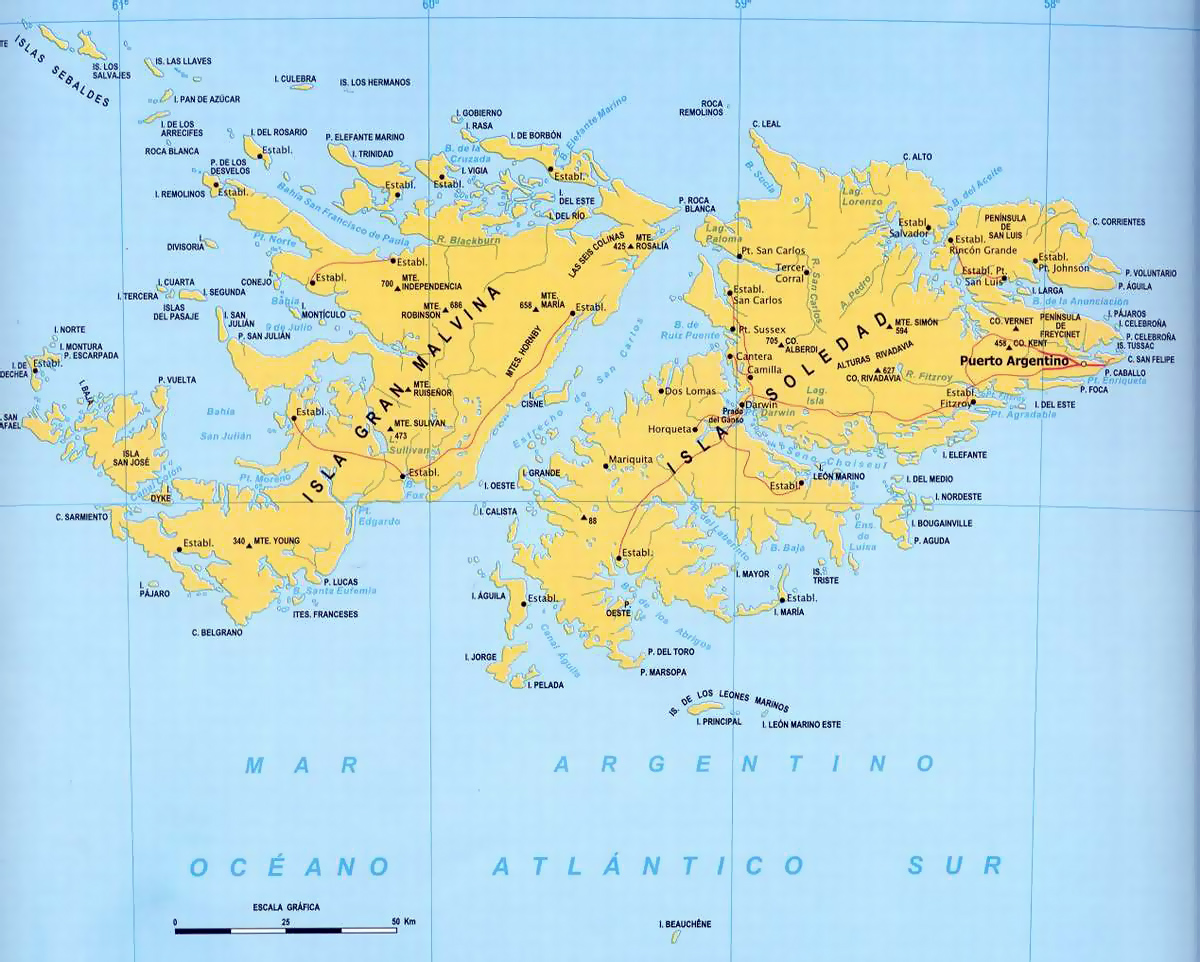

The archipelago consists of two main islands: East Falkland and West Falkland. There are also about 776 smaller islands. That’s a lot of coastline for a place with only about 3,500 people. Most of those folks live in Stanley, the capital on East Falkland. If you're looking at a map and trying to find the "heart" of the place, that’s it.

Why the Landscape Looks So Strange

The terrain is basically treeless. Windswept. It’s covered in dwarf shrub heath and acid grass. If you’ve ever seen photos of the Scottish Highlands, you’re close. The highest point is Mount Usborne, reaching about 2,313 feet. It’s not exactly Everest, but in the middle of the South Atlantic, it feels massive.

Actually, the "stone runs" are probably the coolest thing you'll see on the map. These are literal rivers of rock—huge quartzite boulders that flowed down hillsides during the Pleistocene era. Charles Darwin saw them when the HMS Beagle stopped by in 1833 and 1834. He was baffled. He called them "extraordinary" and spent a lot of time trying to figure out how they formed. He wasn't just there for the rocks, though; his observations of the Falkland Steamer Duck and the now-extinct Warrah (a fox-like wolf) helped shape his early thoughts on evolution.

A Map Defined by Two Names

Here is where things get tricky. If you're in Buenos Aires, every map of South America Falkland Islands will show the "Islas Malvinas." They’ll likely be colored the same as the Argentine mainland. In London, they are the Falkland Islands, a British Overseas Territory.

This isn't just a naming quirk.

📖 Related: TSA PreCheck Look Up Number: What Most People Get Wrong

- The British Claim: They point to continuous administration since 1833. They also lean heavily on "self-determination." In 2013, the islanders held a referendum. Out of 1,517 votes cast, 1,513 people voted to remain British. That’s 99.8%. Hard to argue with that kind of consensus.

- The Argentine Claim: They say they inherited the islands from the Spanish Crown in the early 1800s. They argue the British forcibly removed the Argentine population in 1833 and that "self-determination" doesn't apply to a "settler population" planted by a colonial power.

Google Maps actually handles this in a pretty clever (or cowardly, depending on who you ask) way. If you view the map from Argentina, it shows Argentine names. If you view it from the UK, it shows British names. It’s a localized truth.

The 1982 Conflict and Its Lasting Marks

You can't talk about the map without talking about the war. In April 1982, the Argentine military junta invaded. Margaret Thatcher sent a task force 8,000 miles to take them back. It lasted 74 days.

The scars are still there.

If you hike around Stanley today, the map comes alive with battlefield sites like Mount Tumbledown and Goose Green. There are still areas marked with "Danger: Mines" signs, though a massive demining effort led by Zimbabwean experts (who are world-renowned for this) officially finished clearing the islands in 2020. For decades, those minefields actually became accidental nature preserves because humans couldn't go there, but the penguins were too light to trip the sensors.

It's one of those weird, dark ironies of history.

Getting There: The Logistics of Isolation

Looking at the map of South America Falkland Islands, you’d think it’s a quick hop from Patagonia. It isn't. Because of the ongoing sovereignty dispute, direct travel between Argentina and the islands is... complicated.

Most travelers take one of two routes.

First, there’s the "Air Bridge" from the UK. This is a long-haul flight operated by the Ministry of Defence from RAF Brize Norton. It stops at Ascension Island (usually) for fuel. It’s expensive and feels very "military."

👉 See also: Historic Sears Building LA: What Really Happened to This Boyle Heights Icon

Second, there’s the commercial route through Chile. LATAM flies from Santiago to Mount Pleasant Airport. This flight usually stops in Punta Arenas. Once a month, it’s supposed to stop in Rio Gallegos, Argentina, as part of a diplomatic agreement, but those flights get cancelled or protested more often than you'd think.

Life on the "Camp"

Outside of Stanley, everything is referred to as "the Camp." This comes from the Spanish word campo for countryside.

Life here is rugged. Most people in the Camp are involved in sheep farming. In fact, for a long time, wool was the only thing keeping the economy alive. That changed in the 80s and 90s when the islands started selling fishing licenses. Now, squid (specifically Loligo and Illex) is the real king.

The map of the islands' economy shifted almost overnight. Suddenly, a tiny territory was self-sufficient, except for defense. They even have a burgeoning oil exploration sector, though that’s a whole other layer of political drama with Argentina.

Wildlife: The Real Residents

If you’re a photographer, the map of the Falklands is basically a treasure map.

You’ve got five species of penguins: King, Gentoo, Rockhopper, Magellanic, and the occasional Macaroni. Volunteer Point is the place to be if you want to see the King penguins. It’s a long, bumpy 4x4 drive from Stanley, but standing among 1,000+ regal-looking birds with orange neck patches is something else.

Then there are the Black-browed Albatrosses. About 70% of the world's population nests here. Steeple Jason, a remote island in the far northwest of the archipelago, is home to the largest colony. Looking at a map, Steeple Jason is just a tiny sliver of rock, but biologically, it’s one of the most important places on Earth.

What Most People Get Wrong

People often think the Falklands are tropical because they see "South America" and think "Brazil."

✨ Don't miss: Why the Nutty Putty Cave Seal is Permanent: What Most People Get Wrong About the John Jones Site

Nope.

Think "Antarctica-lite." Even in the summer (December to February), the average high is only around $15^{\circ}C$ (59°F). The wind is constant. It’s the kind of wind that gets into your bones. When you're looking at the map of South America Falkland Islands, remember that they are much closer to the Antarctic Circle than they are to the Equator.

Another misconception is that the islands are just a military base. While there is a significant British military presence at Mount Pleasant, the civilian culture is vibrant. They have their own radio station, their own newspaper (The Penguin News), and a very distinct "Falklander" identity. They aren't just "British people living abroad." They are a distinct community with roots going back nine generations.

Practical Steps for the Curious

If you’re actually planning to use a map of South America Falkland Islands to navigate a trip, you need to be prepared. This isn't a "wing it" kind of destination.

- Book Way in Advance: There are limited beds on the islands. Between cruise ship passengers and land-based tourists, things fill up fast.

- Understand the "Internal Flights": To get between islands, you use FIGAS (Falkland Islands Government Air Service). These are small Islander aircraft. There’s no set schedule; they plan the routes every day based on who needs to go where. You call the night before to find out your "check-in" time. It’s like a flying taxi service.

- Respect the Land: Many of the best wildlife spots are on private farms. You need permission to cross the land, or you need to be with a registered guide.

- Currency: They use the Falkland Islands Pound (FKP), which is pegged 1:1 with the British Pound (GBP). You can use UK coins and notes there, but you can’t use Falkland Islands money back in London.

The islands are a place where the map tells a story of survival. Whether it's the kelp forests sheltering sea lions or the small settlements clinging to the coast, everything about the geography screams "resilience."

When you look at that map of South America Falkland Islands, don't just see the lines and the names. See the "stone runs" Darwin studied. See the penguin colonies that outnumber the humans. See the complex history that still keeps diplomats awake at night. It’s a small place, sure, but it’s a big story.

To truly understand the region, start by comparing historical maps from the 1700s to modern satellite imagery. You’ll see how the names shifted from French (Étoile) to Spanish to English, reflecting the shifting tides of global power. If you're visiting, grab a physical topographic map in Stanley; the detail of the coastlines and the "Camp" tracks provides a much better perspective than any digital screen ever could. Look for the "settlement" markers—each one represents a family and a history that is much tougher than the landscape suggests.