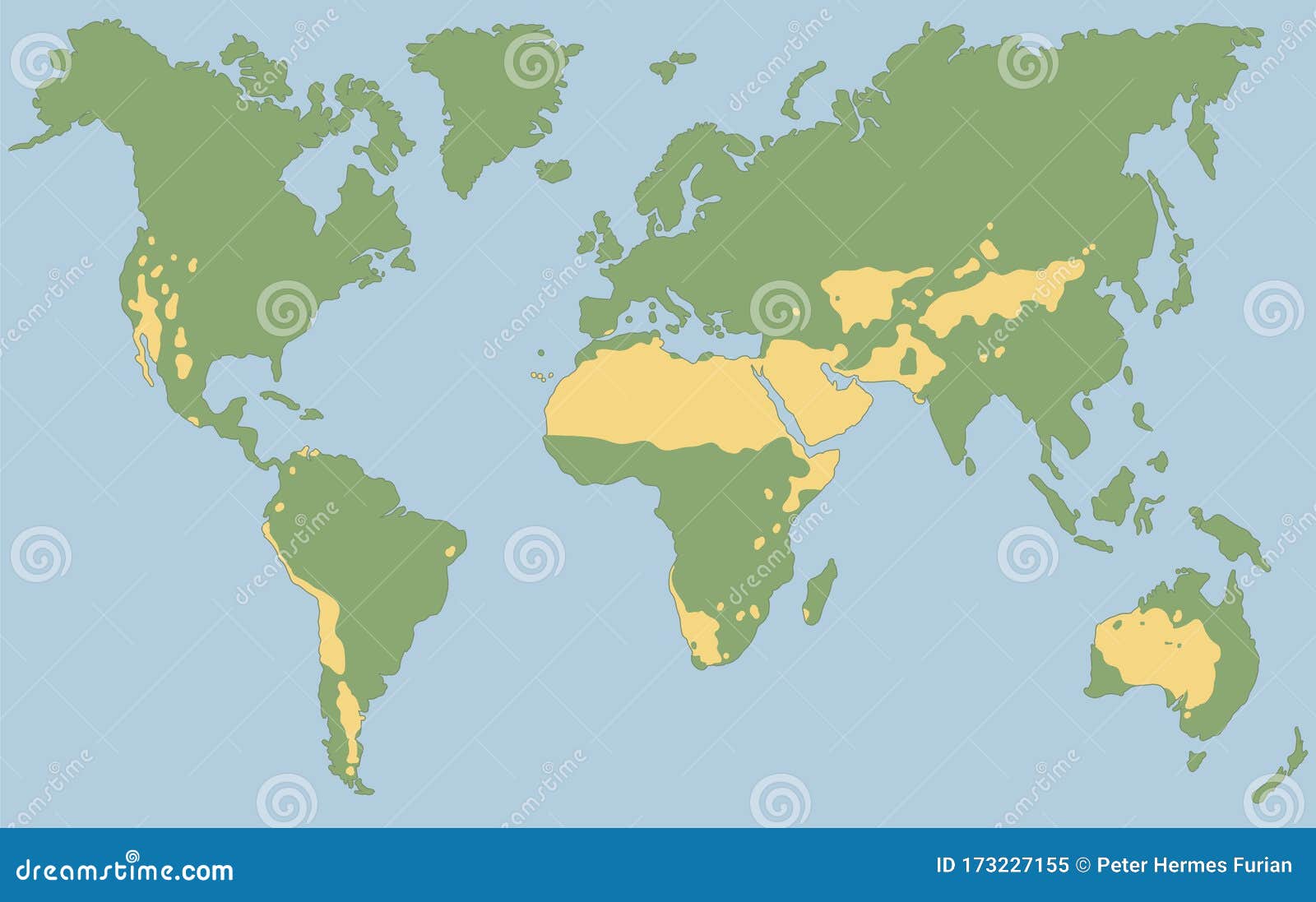

You’ve seen the maps. Usually, it’s a standard projection of the Earth with big, sandy-colored blobs splashed across Northern Africa, the Middle East, and the Australian Outback. But honestly, most people look at a map of deserts in the world and see it all wrong. They see "dead space." They see nothingness.

That’s a mistake.

Deserts cover about one-third of the Earth’s land surface. They aren't just sand dunes and camels. In fact, if you’re looking at a map and expecting a giant sandbox, you’re going to be pretty confused when you hit the Antarctic—the largest desert on the planet. Yeah, it's made of ice. But by definition, it's a desert because it barely gets any precipitation. It’s bone-dry.

When we talk about these regions, we’re talking about moisture, or the lack thereof. It's a game of evaporation versus precipitation. If the sky isn't dropping water but the ground is losing it, you've got a desert. Simple. But the way these biomes are distributed across the globe isn't random. There’s a very specific, almost mechanical reason why they sit where they do.

Reading the Map of Deserts in the World: The 30-Degree Rule

Take a look at a globe. Focus on the lines of latitude at 30 degrees North and 30 degrees South. Notice anything? This is the "Desert Belt." Most of the big names—the Sahara, the Arabian, the Mojave, the Thar—are parked right along these lines.

Why? Atmospheric circulation.

✨ Don't miss: Weather at Kelly Canyon: What Most People Get Wrong

Air rises at the equator because it's hot. As it rises, it cools and dumps all its moisture as rain (hence the jungles). By the time that air travels north or south to the 30-degree mark, it’s cold, dry, and heavy. It sinks. As it sinks, it warms up, sucking moisture out of the ground like a giant sponge. This creates "subtropical deserts." It's basically a global-scale air conditioning system that accidentally created the Sahara.

But not every desert follows the rules. Some are "rain shadow" deserts. Think of the Gobi in Asia or the Great Basin in the US. These happen because big mountains get in the way. Clouds hit the Himalayas or the Sierras, try to climb over, lose all their rain on the windward side, and arrive on the other side as dry ghosts.

The Giants You Know (and the Ones You Don’t)

Most people point to the Sahara first. It’s the size of the United States. It's massive. But it’s only the third-largest desert globally.

- Antarctic Desert: 14.2 million square kilometers. Cold. Dry.

- Arctic Desert: Roughly 13.9 million square kilometers. Also cold.

- Sahara Desert: 9.2 million square kilometers. The king of the "hot" ones.

Then you have the coastal deserts, which are weirdly fascinating. The Atacama in Chile is the best example. It sits right next to the Pacific Ocean, yet some parts of it haven't seen a drop of rain in recorded history. It’s so dry that NASA uses it to test Mars rovers. The cold Humboldt Current off the coast cools the air so much that it can’t hold moisture, creating a permanent fog that never actually turns into rain.

The Arabian and the Australian Outback

The Arabian Desert is a massive block of sand covering nearly the entire Arabian Peninsula. It’s home to the Rub' al Khali, or the "Empty Quarter," which is the largest continuous body of sand in the world. It’s a place where the dunes can reach 250 meters high.

🔗 Read more: USA Map Major Cities: What Most People Get Wrong

Down south, the Great Victoria Desert and the Great Sandy Desert dominate the Australian map. Australia is actually the driest inhabited continent. Unlike the Sahara, much of the Australian desert is covered in scrub and hardy vegetation, but it’s still incredibly inhospitable if you don’t know what you’re doing.

Why These Maps Are Changing Right Now

A map of deserts in the world from 1950 looks different than one from 2026. This isn't just about borders; it's about "desertification."

Land degradation is turning fertile soil into dust. In the Sahel region, just south of the Sahara, the desert is effectively "creeping" southward. Overgrazing, deforestation, and shifting rainfall patterns are stripping the land of its ability to hold water. According to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), we’re losing millions of hectares of productive land every year.

It’s not just a "nature" problem. It’s a food security problem. When the map changes, people have to move.

The Misconception of Barrenness

We tend to think of these places as empty. That’s factually wrong. Deserts are incredibly biodiverse, just in a "low-density" kind of way. From the fennec foxes of the Sahara to the saguaro cacti of the Sonoran, life has found ways to thrive in extremes. Some seeds can sit in the dirt for ten years, waiting for a single rainstorm to bloom.

💡 You might also like: US States I Have Been To: Why Your Travel Map Is Probably Lying To You

Then there's the human element. The Bedouin in the Middle East, the San people in the Kalahari, and the Tuareg in North Africa have lived in these "inhospitable" zones for millennia. They don't see a wasteland. They see a home with very specific rules. If you break the rules, you die. If you follow them, the desert provides.

Navigating the Terrain: Practical Realities

If you’re planning to visit or study these regions, you have to look past the 2D map. A map won't tell you about "diurnal temperature variation." In the desert, the air is so dry it can’t hold heat. You might be sweating at 45°C (113°F) at noon and shivering at 0°C (32°F) by midnight.

- Water is heavy. You need about 4-6 liters a day just to survive in high heat.

- Sand isn't everywhere. Most deserts are actually "regs"—stony plains or rocky plateaus. Only about 20% of the Sahara is sand.

- Flash floods kill. Sounds crazy, right? But because the ground is baked hard, it can't absorb water. A distant rainstorm can send a wall of water down a dry canyon (wadi) in minutes.

Where to Look Next

Understanding a map of deserts in the world is about recognizing the limits of our planet's hospitality. These aren't just patches of brown on a page; they are dynamic, shifting environments that dictate where we can live and what we can eat.

For those looking to go deeper, check out the Digital Observatory for Protected Areas (DOPA) or the USGS Global Ecosystems maps. They provide high-resolution data on how these regions are shifting in real-time. If you're traveling, use topographic maps, not just road maps. Know where the "depressions" are. In the desert, the landscape is the boss.

The most important takeaway? Respect the dry lines. Whether it's the high-altitude cold of the Tibetan Plateau or the searing heat of Death Valley, the desert doesn't negotiate. It just exists. And it’s expanding. Keeping an eye on these maps isn't just for geographers anymore—it’s for anyone interested in where the world is heading over the next few decades.

Actionable Steps for Further Research:

- Examine the Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps. These go beyond "sand" and show exactly where "BWh" (Hot Desert) and "BWk" (Cold Desert) climates sit.

- Monitor the Great Green Wall project. This is an active, multi-nation effort in Africa to plant a 8,000km "wall" of trees to stop the Sahara's expansion. It’s the best real-world example of humans trying to redraw the map.

- Use satellite imagery. Tools like Google Earth Engine allow you to see time-lapses of desertification in places like the Aral Sea (which is now mostly the Aralkum Desert) to understand how quickly these maps change.