Chemistry textbooks love to draw a thick, jagged line down the right side of the periodic table. They call it the "staircase." It’s meant to be this clean, undeniable border separating the aggressive metals from the standoffish nonmetals. But honestly? Nature isn't that tidy. When you ask where on the periodic table are metalloids located, the simple answer is that they sit right on that diagonal line. The real answer is that they are the chemical world’s ultimate fence-sitters, living in a narrow strip that starts at Boron and zig-zags down to Polonium.

They are the "in-betweeners." They aren't quite shiny enough to be metals, but they aren't brittle enough to be pure nonmetals. If the periodic table were a neighborhood, the metalloids would be the houses sitting exactly on the county line, paying taxes to two different jurisdictions. This weird placement is exactly why your smartphone works and why the modern world looks the way it does.

The geography of the "In-Between"

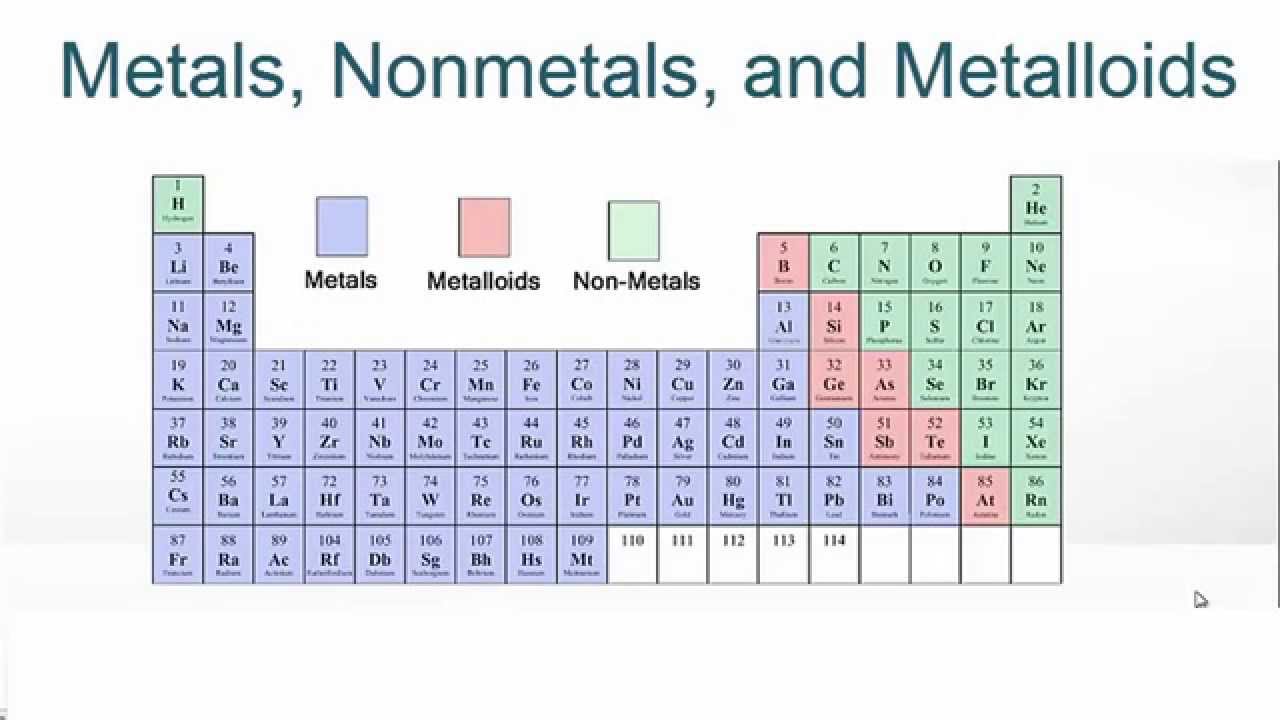

To find them, you look at the p-block. Specifically, you’re looking at groups 13 through 16. Most people identify six elements as the "classic" metalloids: Boron (B), Silicon (Si), Germanium (Ge), Arsenic (As), Antimony (Sb), and Tellurium (Te). Some scientists, like those following the IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) guidelines, might throw Astatine or Polonium into the mix. It's a debate that’s been raging in faculty lounges for decades because there is no official, universally accepted definition of what a metalloid actually is.

The staircase begins at Group 13 with Boron. As you move one row down and one column to the right, you hit Silicon. Move down and right again, and you find Germanium and Arsenic. It’s a diagonal descent.

Why there? It’s all about the electrons.

Elements on the far left (metals) have electrons they are dying to get rid of. Elements on the far right (nonmetals) are desperate to grab more. Metalloids sit in that geographic sweet spot where the "pull" from the nucleus is just strong enough to hold onto electrons, but not strong enough to stop them from moving around under the right conditions. This creates a state of perpetual identity crisis.

✨ Don't miss: Maya How to Mirror: What Most People Get Wrong

Silicon: The king of the staircase

If you’re wondering why this specific location matters, look at Silicon. It’s located in Group 14, right under Carbon. Because of where on the periodic table are metalloids located, Silicon has four valence electrons. It can share them in a way that makes it a "semiconductor."

Basically, a metal like Copper is always "on"—electricity flows through it whether you like it or not. A nonmetal like Sulfur is "off"—it blocks flow. Silicon, sitting on that magic staircase, can be toggled. With a little bit of heat or a tiny bit of "doping" (adding impurities like Phosphorus), you can force it to conduct. This on-off capability is the physical basis for the binary 1s and 0s in your computer’s CPU. Without the metalloids' specific placement between the conductors and the insulators, Silicon Valley would just be a valley full of very expensive sand.

The "Fuzzy" border problem

Here is the thing about that staircase: it’s kinda arbitrary. Depending on who you ask, the list of metalloids changes.

For instance, Selenium is sometimes invited to the party. In its gray form, it conducts electricity better in the light than in the dark. That’s a very metalloid-like trait. However, most chemists shove it into the nonmetal category because its chemical behavior leans more toward its neighbor, Sulfur.

Then there’s the Polonium and Astatine situation. These are heavy, radioactive, and incredibly rare. Because they sit at the bottom of the staircase, they should be metalloids. But they are so unstable that it's hard to test their "metalloid-ness" in a lab without the sample vaporizing itself from its own radioactive heat.

🔗 Read more: Why the iPhone 7 Red iPhone 7 Special Edition Still Hits Different Today

The location isn't just a coordinate; it's a gradient. As you move down the staircase toward the bottom of the table, the elements get more "metallic." As you move up and to the right, they get more "nonmetallic." Boron, at the top, is very much like a nonmetal. Antimony, near the bottom, looks so much like a metal that you’d swear it was a piece of Silver until you hit it with a hammer and it shatters into a million pieces.

[Image showing the metallic vs non-metallic gradient on the periodic table]

Chemical chameleons in action

Let’s talk about Arsenic. Everyone knows it as a poison, but in the world of periodic table geography, it’s a master of disguise. Because it sits in Group 15, right on the border, it can behave like a metal when it reacts with certain elements and a nonmetal with others.

- Physical appearance: It has a gray, metallic luster. It looks like a heavy metal.

- Behavior: It’s brittle. You can’t stretch it into a wire like you can with Gold or Copper.

- Chemistry: It forms amphoteric oxides. This is a fancy way of saying its oxides can act as both an acid and a base.

This dual nature is a direct result of being in the "borderlands." Metals generally form basic oxides. Nonmetals form acidic ones. Metalloids? They do both. They are the bilingual citizens of the chemistry world, speaking both languages fluently depending on who they are talking to.

Why some experts disagree on the map

You’ll see some periodic tables where the staircase is colored differently. Some include Carbon (in its graphite form) or Phosphorus. Physicists and chemists often argue about this because they prioritize different things. A physicist looks at "band gap"—how much energy it takes to move an electron. A chemist looks at how the element bonds with Oxygen.

💡 You might also like: Lateral Area Formula Cylinder: Why You’re Probably Overcomplicating It

This disagreement exists because the "metalloid" label is more of a description than a hard category. Unlike the Noble Gases, which have a very specific electron configuration that makes them a closed club, metalloids are defined by their mediocrity. They aren't the best conductors, aren't the best insulators, aren't the most reactive, and aren't the most stable. But in science, mediocrity is incredibly useful.

Practical insights for using this knowledge

If you’re studying for a test or trying to understand materials science, don’t just memorize the list. Look at the neighbors.

- Check the neighbors: If an element is touching the staircase but is to the left (like Aluminum), it’s usually a metal. Aluminum is the weird exception—it touches the line but is definitely a metal.

- Look for the "Semiconductor" tag: If you hear an element described as a semiconductor, you are almost certainly looking at a metalloid or a compound made of one.

- Predict the brittleness: If you find an element on that diagonal line, assume it’s going to be brittle. Even if it looks like a shiny piece of steel (like Germanium), it will shatter like glass if dropped.

- Temperature sensitivity: Metalloids are unique because their conductivity often increases as they get hotter. Metals are the opposite; they get worse at carrying current when they heat up.

To truly master the periodic table, stop thinking of it as a grid of boxes and start seeing it as a map of competing forces. The metalloids are the "DMZ" where the pull of the nucleus and the freedom of the electrons are perfectly balanced. This balance is what allows us to create transistors, LEDs, and solar cells. They are the bridge between the world of heavy construction (metals) and the world of life and gases (nonmetals).

For your next steps, take a closer look at a high-resolution periodic table and trace the line yourself. Focus on the transition from Group 13 to 16. If you want to see this in the real world, compare a piece of Silicon (a metalloid) to a piece of Aluminum (a metal). The Aluminum will bend; the Silicon will snap. That physical difference is the tangible proof of where those elements sit on the cosmic map.