When you look at a globe, your eyes are naturally drawn to that massive, tawny-colored smudge stretching across the entire top third of Africa. That's it. That’s the Sahara. But if you’re trying to pinpoint exactly where is the Sahara desert located on a map, you’ll realize it isn't just a "spot." It's a continent-defining monster. It covers roughly 3.6 million square miles. To put that into perspective, you could basically drop the entire United States, including Alaska and Hawaii, inside its borders and still have room to spare.

It's huge.

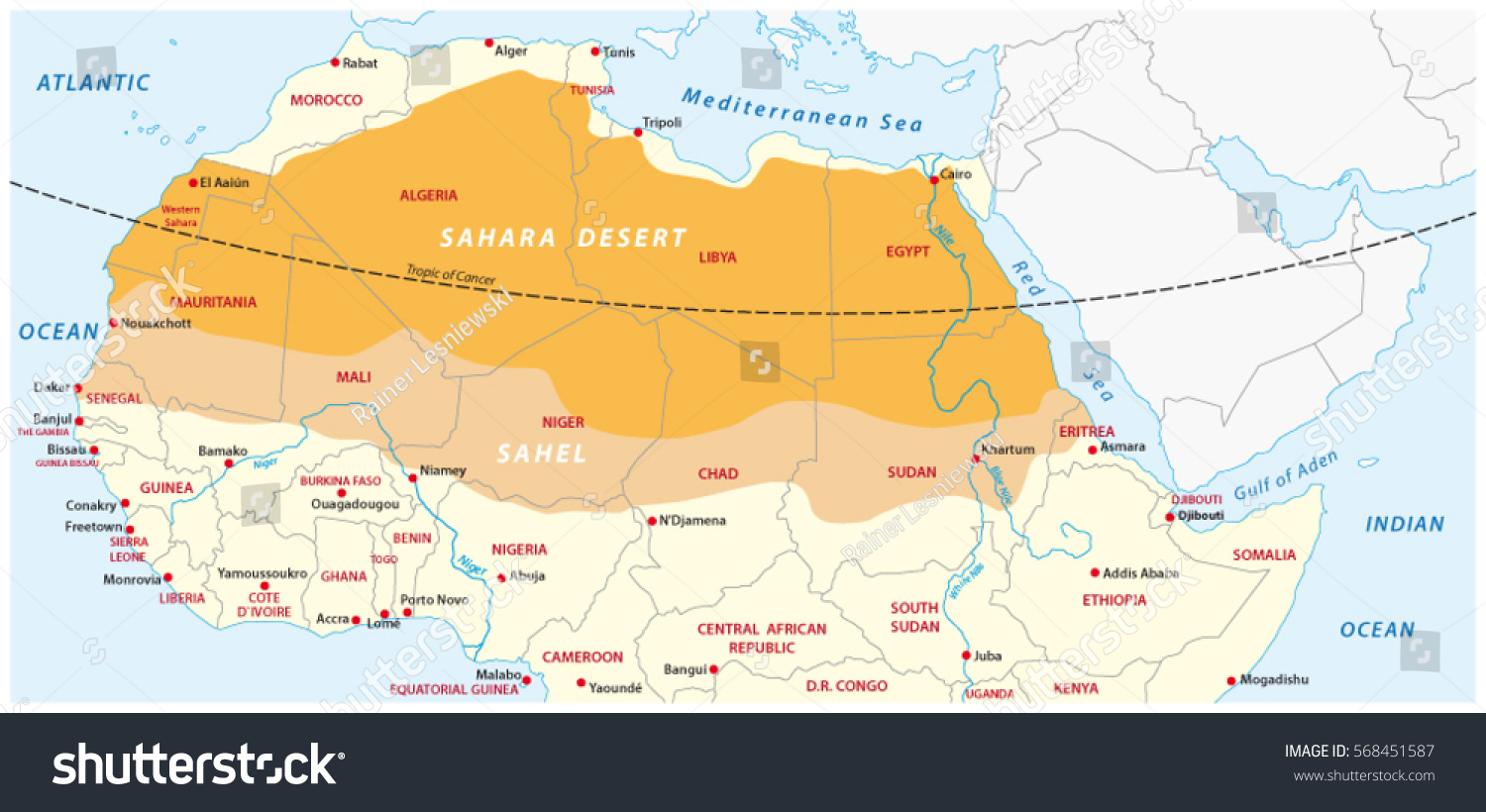

Most people think of the Sahara as just "North Africa," but that’s a bit of a generalization. It actually touches eleven different countries. We’re talking Algeria, Chad, Egypt, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Western Sahara, Sudan, and Tunisia. If you’re tracing it with your finger on a physical map, you’ll see it starts at the Atlantic Ocean in the west and doesn't stop until it hits the Red Sea in the east. To the north, it’s bounded by the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlas Mountains. To the south, it transitions into the Sahel, a semi-arid belt of tropical savanna that acts as a buffer between the sand and the jungle.

Why the Map Can Be Deceptive

Maps are kinda lying to you about the Sahara.

Standard Mercator projections—the kind you probably saw in your middle school geography class—distort the size of landmasses near the poles and the equator. Because the Sahara sits right across the Tropic of Cancer, its true scale is often understated. It isn't just a big beach. It’s a complex network of plateaus, mountains, and salt flats.

💡 You might also like: Why the Nutty Putty Cave Seal is Permanent: What Most People Get Wrong About the John Jones Site

If you look at a topographical map, you’ll notice it isn’t all flat sand dunes. In fact, those iconic "ergs" (sand seas) only make up about 25% of the desert. The rest? It’s mostly "hamada," which is basically barren, rocky plateaus. You’ve also got massive mountain ranges like the Ahaggar in Algeria and the Tibesti in Chad. Emi Koussi, a shield volcano in the Tibesti Mountains, reaches over 11,000 feet. That’s higher than many peaks in the Rockies.

The Sahara is moving, too. It’s not a static line on a piece of paper. Since the early 20th century, the desert has expanded by about 10%. This happens through a process called desertification, where the southern border (the Sahel) loses vegetation and turns into sand. So, if you’re looking at a map from 1950, it’s technically wrong. The Sahara is bigger now.

The Border Paradox: Where Does It Actually Start?

Pinpointing the exact northern and southern limits of the Sahara is honestly a nightmare for geographers. Most scientists use the "100mm isohyet." This is a fancy way of saying they draw the line wherever the average annual rainfall drops below 100 millimeters (about 4 inches).

North of this line, you get Mediterranean scrub. South of it, you get the desert.

📖 Related: Atlantic Puffin Fratercula Arctica: Why These Clown-Faced Birds Are Way Tougher Than They Look

In the south, things get even blurrier. The transition into the Sahel is defined by the 150mm rainfall line. But because weather is chaotic, these lines shift every single year. During the "Green Sahara" periods—the most recent one ended about 5,000 years ago—this entire region was covered in lakes and grasslands. You can still see rock art in the Tassili n'Ajjer mountains showing hippos and giraffes in places that are now total dust.

Key Landmarks to Find on Your Map

If you want to orient yourself, find these three points:

- The Nile River: This is the only major river that successfully fights its way through the eastern Sahara. It creates a thin, green ribbon of life through Egypt and Sudan. Without it, the pyramids would be sitting in the middle of nowhere.

- The Atlas Mountains: This range acts like a giant wall in the northwest (Morocco and Algeria), trapping moisture from the Atlantic and preventing it from reaching the interior. This "rain shadow" is a big reason why the Sahara is so dry.

- The Bodélé Depression: Located in Chad, this is the lowest point in the Sahara. It’s a massive dried-up lake bed. Wind storms here kick up huge amounts of dust that actually blow across the Atlantic Ocean to fertilize the Amazon rainforest. Geography is weird like that.

Life in a Place That Shouldn't Have It

How do people live there? Oases.

If you zoom in on a high-resolution satellite map, you’ll see tiny dots of green. These are spots where underground aquifers reach the surface. The Siwa Oasis in Egypt or the Ghardaïa in Algeria are world-famous. These aren't just puddles; they are ancient cities that have survived for thousands of years because of "fossil water"—water that was trapped underground back when the Sahara was green.

👉 See also: Madison WI to Denver: How to Actually Pull Off the Trip Without Losing Your Mind

Navigating the Modern Sahara

Today, finding where is the Sahara desert located on a map is easy with GPS, but crossing it is still incredibly dangerous. There are only a few major "paved" routes, like the Trans-Sahara Highway that runs from Algiers to Lagos. Most of the desert remains roadless.

When you look at the political map, you’ll see straight lines. These aren't natural. Many of the borders in the Sahara were drawn by European colonial powers with a ruler and a pen in the late 19th century, often ignoring the traditional migratory routes of the Tuareg and Berber peoples who have called the desert home for millennia.

Actionable Insights for Geographic Study

If you’re researching the Sahara for a project or planning a trip to its fringes (like Merzouga in Morocco), keep these steps in mind:

- Check the season: Don't just look at the location; look at the climate data. In the central Sahara, temperatures can swing from 120°F (50°C) during the day to freezing at night.

- Use Satellite Imagery: Standard maps don't show the difference between "Reg" (stony plains) and "Erg" (sand dunes). Google Earth is your best friend here to see the actual texture of the land.

- Acknowledge Political Realities: Large portions of the central Sahara, particularly around the borders of Mali, Niger, and Libya, are often subject to travel warnings due to regional instability. Always check current government travel advisories before looking for "off-the-beaten-path" spots.

- Understand the Dust: If you are studying global weather patterns, look at the "Saharan Air Layer." This massive plume of dust affects everything from hurricane formation in the Caribbean to air quality in Florida.

The Sahara isn't just a desert; it’s a living, breathing part of the Earth’s climate engine. It’s a place of extremes where the map is constantly being rewritten by wind, sand, and time.