Everyone asks the same thing the second a blob of red appears on the satellite map: where is the hurricane gonna hit? It is the only question that matters when you're staring at a tropical depression spinning out in the Atlantic or churning through the Gulf of Mexico. You want a straight answer. You want a dot on a map. But the reality of hurricane forecasting is a messy, beautiful, and sometimes frustrating blend of high-stakes physics and probability.

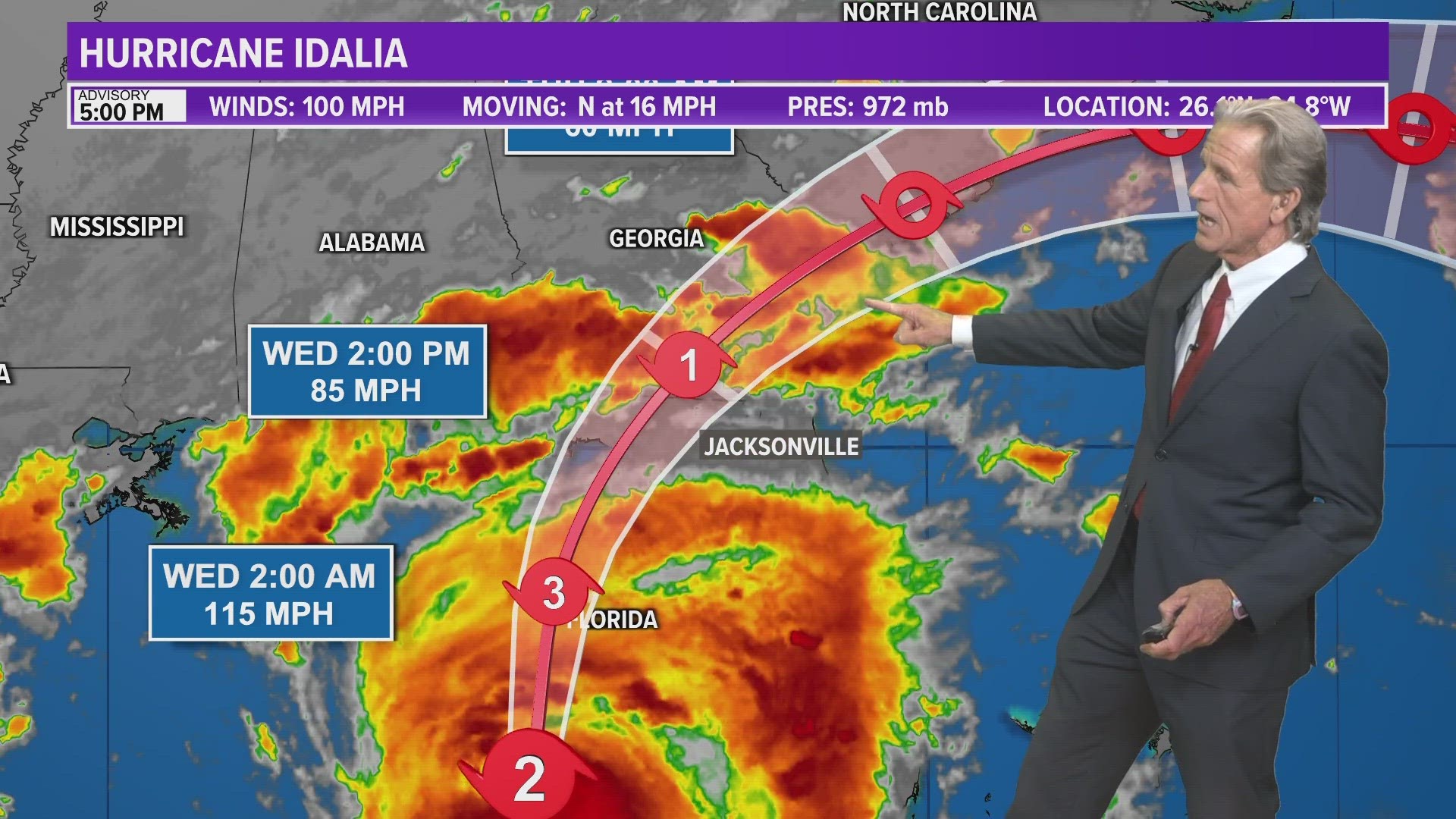

People get obsessed with "the line." You know the one. That thin, black line running down the center of the National Hurricane Center (NHC) forecast cone. If that line points at your city, you panic. If it shifts fifty miles left, you think you’re safe. That’s a mistake. A massive one.

The "Cone of Uncertainty" isn't a strike zone. It is a historical margin of error. Honestly, it represents where the center of the storm might go about two-thirds of the time. It doesn't tell you a thing about how wide the wind field is or where the rain will dump ten inches of water. You've got to look past the graphics if you want to stay dry.

The chaos of the "Spaghetti Models"

When you start digging into where is the hurricane gonna hit, you’ll inevitably run into spaghetti models. These are those colorful, chaotic maps with twenty different lines all squiggling in different directions. They look like a toddler had a field day with some crayons. But they are actually the output of different computer simulations—the GFS (the American model) and the ECMWF (the European model) are the big two everyone talks about.

Meteorologists like Dr. Levi Cowan at Tropical Tidbits or the team at the NHC don't just pick their favorite color. They look for "clustering." If ten different models all show the storm curving toward the Outer Banks of North Carolina, confidence goes up. If one line goes to New Orleans and another goes to Bermuda? Well, then nobody knows anything yet.

The atmosphere is a fluid. It’s always moving. A high-pressure ridge over Bermuda might act like a brick wall, forcing a hurricane to turn south. A trough of low pressure dipping over the United States can act like a vacuum, sucking the storm toward the coast. These features are invisible to the naked eye, but they dictate exactly where that hurricane is gonna hit.

Why the "Right Front Quadrant" is the real danger

Location is everything, but so is orientation. Let’s say the storm is moving North. The "right-front quadrant" is almost always the nastiest part of the storm. Why? Because the storm’s forward motion adds to the wind speed. If a hurricane is spinning at 100 mph and moving forward at 15 mph, the winds on that right side are effectively 115 mph.

This is also where the storm surge is usually the worst. The wind is literally pushing the ocean onto the land. Even if the center of the storm misses you by 50 miles, if you are in that right-front quadrant, you might see more damage than someone who had the "eye" pass directly over them.

👉 See also: Why Trump's West Point Speech Still Matters Years Later

Take Hurricane Ian in 2022. For days, the forecast suggested a landfall near Tampa. People in Fort Myers felt relatively safe. But the storm wobbled. Just a tiny shift. It made landfall further south, and the devastating storm surge—the deadliest part—slammed into Lee County. That's why "where is the hurricane gonna hit" isn't just a coordinate. It's a region.

The limit of the Five-Day Forecast

We live in an age of instant data. We want to know ten days out.

Science isn't there yet.

The NHC doesn't even show a cone past five days because the error margin becomes ridiculous. By day seven, a forecast is basically a guess based on climatology. Small errors in the initial data—maybe a weather balloon in Africa missed a reading—can balloon into a 500-mile difference in the forecast a week later. It’s the butterfly effect in real time.

You’ll see people on social media sharing "outflow" charts or "long-range ensembles" that show a Category 5 hitting Miami in two weeks. Ignore them. They are chasing clicks. Professional meteorologists wait for the "recon" flights—the Hurricane Hunters. When those planes fly directly into the eye, they drop sensors called dropsondes. That’s the real data. That’s when we start to truly understand the steering currents.

Water, not wind, is the silent killer

We focus so much on the "Category" of a storm. A Cat 1 sounds "easy" compared to a Cat 4.

That is a dangerous mindset.

✨ Don't miss: Johnny Somali AI Deepfake: What Really Happened in South Korea

Hurricane Florence in 2018 weakened to a Category 1 before it hit the Carolinas. People relaxed. But the storm stalled. It sat there. It dumped over 30 inches of rain in some spots. The inland flooding was catastrophic. The wind didn't destroy those homes—the water did.

When you're asking where is the hurricane gonna hit, you need to check the "Hydrological Outlook." If the storm is moving slow (think 5 mph or less), it doesn't matter what category it is. You are going to have a flood problem.

How to actually track a storm like a pro

Don't rely on a single screenshot from a news app. Follow these steps to get the full picture:

- Check the NHC Public Advisory: This is issued every few hours. It gives the exact coordinates and the current movement speed.

- Look at the Tropical Force Wind Probability: This map shows you the likelihood of seeing 39+ mph winds. It’s often much wider than the cone.

- Watch the "Key Messages": The NHC writes a plain-English summary of the biggest threats. Read it.

- Local Weather Forecast Office (NWS): Your local NWS office (like NWS Miami or NWS Houston) will provide specific impacts for your neighborhood, including expected rainfall totals and surge heights.

The human element of the "Wobble"

Hurricanes aren't perfect circles. They are breathing, pulsating heat engines. As the eye wall replaces itself—a process called an Eyewall Replacement Cycle—the center of the storm can "wobble" or "jog."

A ten-mile jog to the east might mean the difference between a direct hit on a major city and the storm staying just offshore. You cannot account for the wobble more than an hour or two in advance. This is why "Where is the hurricane gonna hit?" remains a question of probabilities until the very last second.

Preparation shouldn't wait for the "H-hour." If you are in the cone, you should act as if you are going to be hit. Period.

Actionable steps for the next 48 hours

If a storm is heading your way, quit refreshing the map every five minutes. It’s bad for your head. Instead, focus on what you can control.

🔗 Read more: Sweden School Shooting 2025: What Really Happened at Campus Risbergska

First, secure your "important stuff" box. Birth certificates, insurance policies, and passports should be in a waterproof bag. Take photos of every room in your house for insurance claims later. It's much easier to prove you had a 70-inch TV if you have a photo of it before the roof leaked.

Gas up your car now. Not tomorrow. Not when the lines are three blocks long. If you have an electric vehicle, charge it to 100%. If you have a generator, test it. Do not run it in your garage. People die every year from carbon monoxide poisoning because they were scared their generator would get stolen in the rain.

Clean your gutters. If they are clogged with leaves, the rain from the outer bands will back up under your shingles. It’s a simple fix that saves thousands in water damage.

Lastly, check on your neighbors. The elderly couple down the street might not have the physical strength to put up shutters or move their patio furniture. A hurricane is a community event. Treat it like one.

Stay tuned to official sources. Use the NHC. Use your local meteorologists. Avoid the "doom-casters" on TikTok. The science is complicated enough without people making up scenarios for engagement. Be smart, stay dry, and keep your eye on the whole storm, not just the center line.

Immediate Checklist:

- Check your local evacuation zone via your county's emergency management website.

- Fill clean containers with drinking water (aim for one gallon per person per day).

- Download an offline map of your area in case cell towers go down.

- Review your flood insurance policy—remember, most have a 30-day waiting period, so if the storm is already named, it's likely too late to buy a new one, but good to know what's covered.