You’ve probably heard since the eighties that the sky is falling—or at least, that the part of the sky keeping us from being crispy-fried by the sun is disappearing. It's one of those environmental stories that felt like a massive emergency, then kind of faded into the background of our collective anxiety. But if you walk outside and look up, you might wonder: where is the hole in the ozone layer right now? Is it still hovering over the penguins, or has it moved?

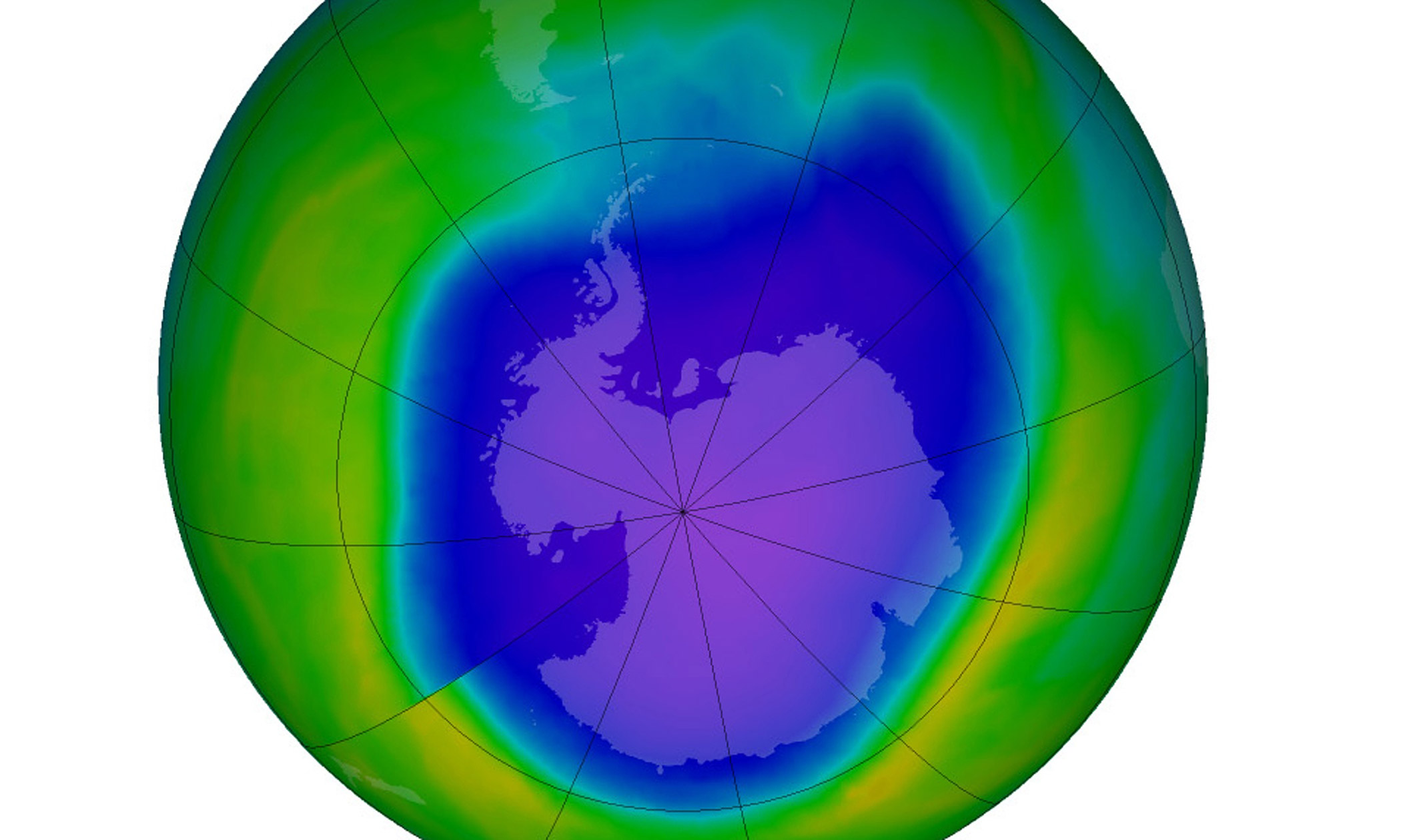

Honestly, the "hole" isn't actually a hole. It’s a thinning. Think of it more like a worn-out patch on an old pair of jeans rather than a literal puncture. And while many people assume it's sitting over the North Pole or maybe some industrial wasteland in the Northern Hemisphere, it's actually located almost exclusively over Antarctica.

It stays there. It grows and shrinks with the seasons.

Why Antarctica?

It feels counterintuitive. You’d think the damage would be right over the places where people actually live and spray hairspray, right? Nope. The chemistry of our atmosphere is a bit of a weird beast. Most of the ozone-depleting substances (ODS) like chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were released in the Northern Hemisphere. But global wind patterns—think of them as massive atmospheric conveyor belts—eventually carry these chemicals toward the poles.

Once they get to the South Pole, things get chilly.

During the dark Antarctic winter, something called the Polar Vortex forms. This is a massive, spinning whirlpool of super-cold air that traps these chemicals. When the temperature drops below -78°C (-108°F), colorful, iridescent clouds called Polar Stratospheric Clouds (PSCs) form. They look beautiful, but they are basically laboratory benches for destruction. They provide a surface for chemical reactions that turn "safe" chlorine into "aggressive" chlorine.

When the sun finally peeks over the horizon in the Southern Hemisphere’s spring (around September), that sunlight hits the trapped chlorine. It triggers a chain reaction. One single chlorine atom can rip apart 100,000 ozone molecules before it's finally neutralized. That is why the where is the hole in the ozone layer question always leads you back to the South Pole every September and October.

The North Pole has one too, sort of

I should mention that the Arctic isn't totally immune. Every now and then, if the winter is exceptionally cold up north, we see a "mini-hole" over the North Pole. We saw a significant one in 2020. However, the Arctic atmosphere is way more chaotic and warmer than the Antarctic. The winds break up more easily, so the "hole" there rarely gets as dramatic or as consistent as the one over the South Pole.

So, if you’re living in New York, London, or Tokyo, you aren't under the "hole." But you are living under a slightly thinner ozone layer than your great-grandparents did.

Does it move?

This is where it gets a bit sketchy for people living in the Southern Hemisphere. As the Antarctic spring ends and the air warms up in November or December, the Polar Vortex breaks apart. All that ozone-depleted air—the "hole" air—starts to drift away from the pole.

✨ Don't miss: Why Your Photos Loading on iPhone is Taking Forever: The Real Fixes

It migrates.

It can drift over South America, Australia, or New Zealand. When this happens, the UV index in those regions can spike. It’s not a permanent hole, but it’s a localized thinning that lasts for a few weeks. It’s a huge reason why sun safety is such a massive deal in places like Melbourne or Christchurch compared to similar latitudes in the North.

The Montreal Protocol: Did we actually fix it?

Back in 1987, the world actually did something smart. We signed the Montreal Protocol. We basically agreed to stop using the chemicals that were eating the ozone. It is arguably the most successful environmental treaty in history.

But here’s the kicker: CFCs are hardy. They don't just vanish. They can hang around in the atmosphere for 50 to 100 years. So even though we stopped pumping them out decades ago, the stuff your parents sprayed on their hair in 1982 is still up there, floating around the stratosphere, waiting for an Antarctic winter to do some damage.

According to Dr. Paul Newman and his team at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, the hole is definitely healing. It’s getting smaller on average. But it’s a slow burn. We’re looking at 2066 before the Antarctic ozone layer fully returns to its 1980 levels.

Climate change is complicating the "healing"

You’d think a warmer planet means a warmer stratosphere and thus less ozone depletion. Physics says no. While the "troposphere" (where we live) is warming up, the "stratosphere" (where the ozone is) is actually cooling down.

This happens because greenhouse gases trap heat close to the Earth's surface, preventing it from reaching the upper layers. A colder stratosphere means more of those nasty Polar Stratospheric Clouds. More clouds mean more ozone destruction. It’s a frustrating paradox where solving one problem—global warming—is intimately tied to the recovery of the ozone layer.

✨ Don't miss: Jeannie T Lee 2025: Why Her New Breakthroughs in Chromosomal Jell-O Actually Matter

There's also the issue of "hidden" emissions. A few years ago, researchers noticed a weird spike in CFC-11 emissions. It turned out some factories in Eastern China were illegally using the stuff to make foam insulation. The good news? Global pressure worked, and those emissions dropped back down. But it proves that we have to keep watching.

How we track it today

We don't just guess where the hole is. We use a massive network of satellites and "ozonesondes."

- Aura Satellite: This NASA bird uses the Microwave Limb Sounder to "see" through clouds and measure the chemical makeup of the atmosphere.

- Copernicus Sentinel-5P: This is the European version. It provides crazy high-resolution maps of ozone density.

- Weather Balloons: Scientists at the South Pole Station literally launch balloons with sensors that fly up into the vortex to take direct samples.

Because of this tech, we can see exactly where is the hole in the ozone layer on any given day. Organizations like the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) publish regular bulletins. If you look at the data from 2023 and 2024, the hole was actually quite large and lasted longer than usual. Why? Some scientists think the massive underwater volcanic eruption of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai in 2022 shot so much water vapor into the stratosphere that it messed with the chemistry.

Water vapor in the stratosphere is a catalyst for ozone loss. Nature occasionally throws us a curveball even when humans are trying to behave.

Is the hole why the Earth is warming?

Common misconception. No.

The ozone hole and global warming are two different issues, though they are cousins. The ozone hole doesn't cause global warming. However, ozone itself is a greenhouse gas. More importantly, the hole has changed the way wind moves around Antarctica. It has actually shifted the "jet stream" in the Southern Hemisphere, which affects ocean currents and how much carbon the Southern Ocean can soak up.

Everything is connected. It’s never as simple as "one gas does one thing."

Real-world impact you can see

If you go to the tip of South America—places like Ushuaia in Argentina—during the late spring, the local news will often give ozone alerts. They tell people to keep their kids inside or wear heavy-duty sunblock because the "edge" of the hole is passing over.

It’s not just humans, either. Phytoplankton in the ocean, which form the base of the entire marine food web, can get damaged by excess UV. If the "hole" stays too long over the productive waters around Antarctica, it can stunt the growth of these tiny plants. That ripples up to krill, then whales, then everything else.

What you can actually do

The "big" work is being done by governments, but the ozone layer isn't out of the woods. Here is how you actually contribute to the recovery:

Check your old appliances. If you have a fridge or air conditioner from before the mid-nineties, it might still contain CFCs or HCFCs. Don’t just dump it in a landfill. If it leaks, that gas goes straight up. Find a specialized recycler who can "recover" the refrigerant.

Watch the fire extinguishers. Some older extinguishers use "halons," which are even worse for the ozone than CFCs. If you have a yellow fire extinguisher (the common color for halon), take it to a hazardous waste facility.

Support atmospheric monitoring. It sounds vague, but funding for NASA and NOAA's satellite programs is what allows us to catch "cheaters" who are still pumping out banned chemicals.

Mind the nitrous oxide. While the Montreal Protocol handled CFCs, it didn't really touch nitrous oxide ($N_{2}O$), which comes from certain fertilizers and industrial processes. It’s now one of the leading human-caused threats to the ozone layer. Eating less meat or supporting sustainable farming helps reduce the demand for the high-nitrogen fertilizers that release this gas.

We are on the right track. The hole is shrinking. It’s a rare win for humanity where we saw a problem, agreed on a solution, and actually stuck to it. We just have to wait for the atmosphere to finish cleaning up the mess we made forty years ago.

Keep an eye on the NASA Ozone Watch website if you want to see the daily satellite imagery. It’s a stark reminder that our atmosphere is a thin, fragile skin, and we're the ones responsible for keeping it intact.