If you remember high school biology, you probably think of a cell as a bag of soup. There’s the nucleus—the "brain"—floating around in some jelly called cytoplasm. Maybe you remember the mitochondria being the powerhouse. But honestly, that "soup" model is totally wrong. If cells were just bags of liquid, they’d collapse into blobs. They’d have no shape. They wouldn't be able to move or divide.

So, where is cytoskeleton located exactly? It’s everywhere. Literally.

It isn't just tucked away in a corner like an organelle. It’s a complex, scaffolding-like network that spans the entire interior of eukaryotic cells, from the outer plasma membrane all the way to the edge of the nucleus. Imagine a building. The cytoskeleton isn't the furniture; it's the steel beams in the walls, the elevators in the shafts, and the tracks the elevators run on.

The Interior Map of the Cell

To understand the location, you have to look at the cytoplasm. This is the space between the cell membrane and the nuclear envelope. The cytoskeleton is woven through this space. It’s a dense thicket of protein fibers. It’s actually so crowded in there that "liquid" is a bad word for it. It’s more like a gel.

These fibers don't just sit there. They are physically anchored. On one end, they often hook into proteins embedded in the plasma membrane. This gives the cell its external tension. On the other end, they cluster around the centrosome near the nucleus. This creates a hub-and-spoke system.

✨ Don't miss: Signs of Heart Issues: Why Most People Miss the Earliest Warnings

It’s dynamic. It’s constantly breaking apart and rebuilding. You might find a heavy concentration of actin filaments right under the "skin" of the cell (the cortex) to help it change shape. Meanwhile, the sturdier microtubules act like highways, stretching from the center out to the edges to ship cargo.

Microtubules, Actin, and the "Where" of it All

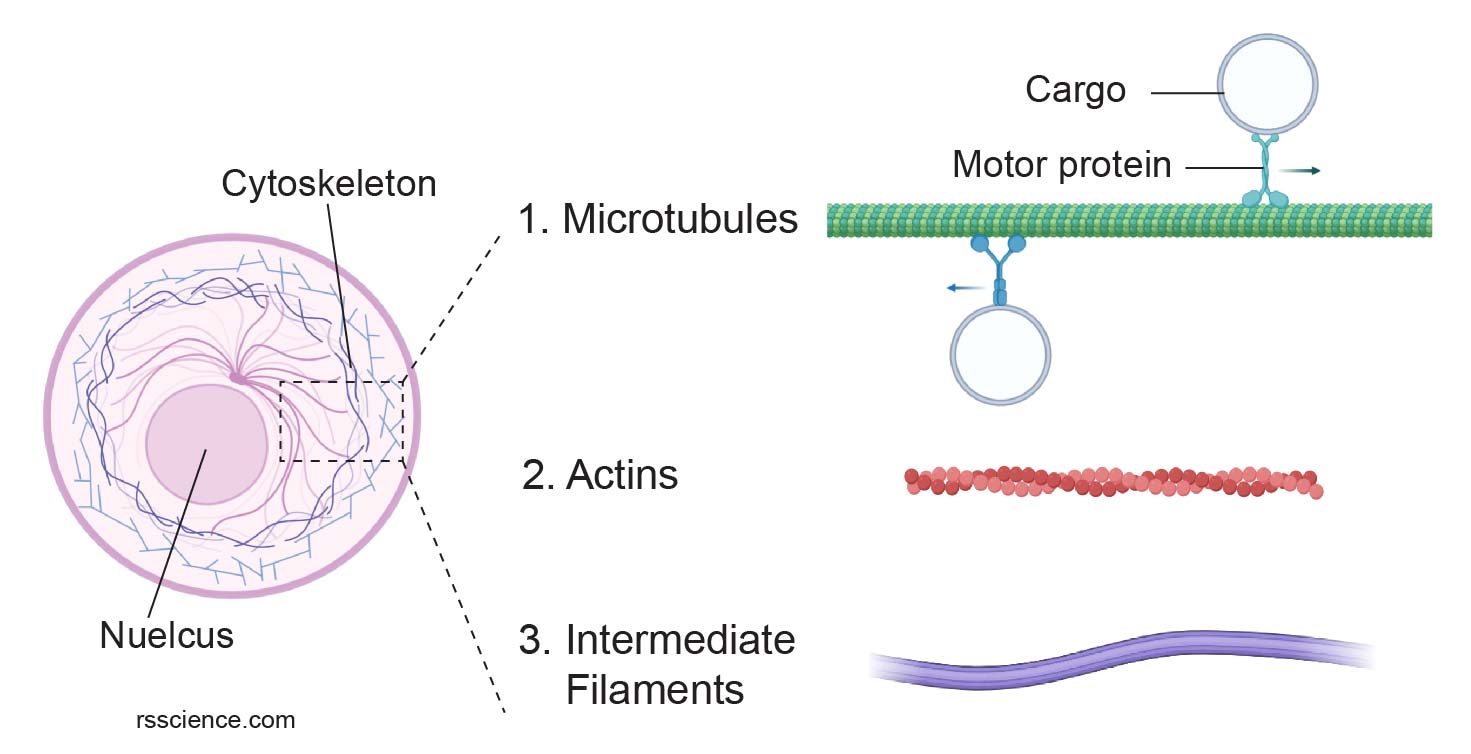

We usually talk about three main types of fibers. Each lives in a slightly different neighborhood within the cell.

Microtubules are the thickest. They usually radiate out from a point near the nucleus called the Microtubule Organizing Center (MTOC). If you’re looking for them, start at the center and follow them out like spokes on a wheel. They reach the very edges of the cell. They are the primary tracks for motor proteins like kinesin and dynein.

Actin filaments (or microfilaments) are the thin ones. You’ll find the highest density of these just beneath the plasma membrane. This area is called the cell cortex. It’s what allows a white blood cell to "crawl" toward an infection. It pushes the membrane forward. If the cytoskeleton wasn't located right there against the edge, the cell would be a static, lifeless sphere.

Intermediate filaments are the "middle" size. These are the most permanent. Unlike the others, they don't assemble and disassemble every five minutes. They are scattered throughout the cytoplasm to provide tensile strength. They also form the nuclear lamina. That’s a specific cage inside the nuclear envelope that keeps the nucleus from being crushed. So, when asking where the cytoskeleton is located, the answer includes the inside of the nuclear lining too.

✨ Don't miss: HHS Regional Offices Closing: What Most People Get Wrong

It’s Not Just Floating Around

A common misconception is that the cytoskeleton is just "in" the cell. No. It is the cell's architecture.

In muscle cells, the cytoskeleton is organized into hyper-specific locations called sarcomeres. Here, actin and myosin are lined up so perfectly they create the "stripes" (striations) you see under a microscope. In neurons, the cytoskeleton stretches for feet. Yes, feet. The microtubules run the entire length of an axon, carrying neurotransmitters from your spine down to your big toe.

If the cytoskeleton were misplaced by even a few nanometers in these cells, they’d fail. In the ears, specialized actin structures called stereocilia stay perfectly positioned to catch sound vibrations. If those fibers lose their location or orientation, you go deaf.

Why the Location Matters for Your Health

Scientists like Dr. Donald Ingber at Harvard have spent decades studying "tensegrity." This is the idea that the location and tension of the cytoskeleton tell the cell what to do. If the cytoskeleton is stretched a certain way because of where it’s anchored, it can actually turn genes on or off.

When the cytoskeleton’s location gets messed up, things go south fast.

✨ Don't miss: Sexsomnia Explained: What Really Happens When You're Having Sex While Sleeping

- Cancer: Cancer cells often have a disorganized cytoskeleton. This allows them to become "squishy" enough to squeeze through blood vessels and spread to other organs (metastasis).

- Alzheimer’s: In this disease, a protein called tau—which usually stabilizes microtubules in brain cells—collapses. The "highways" break down, and the cell dies because it can’t move nutrients around.

- Blistering Diseases: If intermediate filaments aren't properly located and anchored to the skin's basement membrane, your skin literally slides off your body at the slightest touch.

Identifying the Boundaries

So, if you’re looking under a fluorescence microscope, where do you see it?

You’ll see a glow that fills the entire cell body. But it's densest around the nucleus and at the very periphery. It also extends into any "arms" the cell has. Think of cilia (the hairs in your throat that move mucus) or flagella (the tail on a sperm cell). The core of those structures is entirely made of cytoskeleton microtubules arranged in a "9+2" pattern.

The cytoskeleton is even involved in cell-to-cell junctions. It plugs into the spots where one cell touches another, like a biological handshake. This keeps your tissues from falling apart when you stretch.

Summary of Locations

- Cell Cortex: Thick layer of actin filaments just under the plasma membrane.

- Cytoplasm: A sprawling network of all three fiber types.

- Nuclear Lamina: A structural layer of intermediate filaments inside the nucleus.

- Axons/Dendrites: Long parallel runs of microtubules in nerve cells.

- Cilia/Flagella: Core structural microtubules extending outside the main cell body.

- Centrosome: The central "hub" where microtubules are anchored.

Making Use of This Knowledge

Understanding where the cytoskeleton is located helps you visualize how medicine works. Many chemotherapy drugs, like Taxol, actually target the cytoskeleton. Taxol "freezes" microtubules in place. Because the fibers can't move or rebuild, the cancer cell can't divide and eventually dies.

If you're interested in cellular health, focus on the factors that support protein synthesis and stability. Since the cytoskeleton is made entirely of proteins (tubulin, actin, keratin, etc.), your body needs a steady supply of amino acids and the right pH balance to keep these structures from denaturing.

To dig deeper into how these structures move, look up "Intracellular Transport" or "Mechanobiology." These fields study the literal "engines" that run along the cytoskeleton tracks. You can also look into fluorescence microscopy galleries online; seeing the cytoskeleton lit up in neon greens and reds is the best way to realize it isn't just a "part" of the cell—it is the frame that makes life possible.

Check your local university’s open courseware for "Cell Biology 101" if you want to see the math behind how these fibers exert force. It’s surprisingly similar to bridge engineering.