When you open a globe and spin it toward the Western Hemisphere, your eyes usually land on that massive, jagged line running down the left side of South America. That's it. If you've ever wondered exactly where is Andes Mountains located on a map, you basically just need to trace the entire Pacific coastline of the continent. It isn't just a "range" in the way we think of the Smokies or even the Alps. It’s a 4,500-mile-long monster.

It's long. Really long.

Honestly, it’s the longest continental mountain range on Earth. It starts at the very top in Venezuela and doesn't quit until it literally dips into the freezing waters of the Southern Ocean near Tierra del Fuego. Along the way, it cuts through seven different countries: Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina. It’s the spine of a continent. Without this wall of rock, South America would be a completely different place, meteorologically and culturally.

The geographical footprint you can't miss

If you're looking at a digital map right now, look for the coordinates roughly between 10° N and 57° S latitude. The Andes aren't just a thin line, though. In some spots, like the Altiplano in Bolivia, the mountains widen out into a massive plateau that's about 12,000 feet high. You’ve got these two main "cordilleras"—the Oriental and the Occidental—that split apart and leave room for entire civilizations to live in the middle.

It’s a bit of a tectonic mess, really. The range exists because the Nazca Plate and the Antarctic Plate are constantly shoving themselves under the South American Plate. This subduction is what makes the Andes so incredibly high and so incredibly volatile. We're talking about a landscape defined by volcanoes and earthquakes.

Most people think of "The Andes" as one singular thing, but geographers usually break it down into three distinct chunks. You’ve got the Northern Andes (Venezuela and Colombia), the Central Andes (Peru, Bolivia, and northern Chile/Argentina), and the Southern Andes (the rest of Chile and Argentina). Each part feels like a different planet. In the north, it’s lush, tropical, and rainy. By the time you get to the central section, you’re in the Atacama Desert, one of the driest places on the planet. Then, down south, it turns into glaciers and fjords.

Why the location matters for the world's climate

The Andes act as a giant wall. It's a literal barrier for the clouds. Because of where is Andes Mountains located on a map, moisture coming off the Atlantic Ocean gets trapped. The clouds hit the eastern slopes, dump all their rain into the Amazon Basin, and leave the western side—especially in Peru and northern Chile—bone dry.

📖 Related: Bryce Canyon National Park: What People Actually Get Wrong About the Hoodoos

This is the "rain shadow" effect.

Because of this specific placement, we have the Amazon Rainforest on one side and the Atacama Desert on the other. It’s a radical contrast. If the Andes were located just a few hundred miles further east or west, the entire ecology of the planet would shift. The Amazon might not even exist in its current form because it wouldn't have that constant supply of mountain runoff feeding its massive river systems.

Major peaks and where to find them

If you want to pinpoint the highest spot, look toward the border of Argentina and Chile. That’s where Aconcagua sits. At 22,831 feet, it's the highest mountain outside of Asia. It’s a beast.

But it’s not just about height. It’s about the sheer density of peaks.

- Chimborazo in Ecuador: Because of the Earth’s bulge at the equator, the summit of Chimborazo is actually the closest point on the planet to the stars.

- Ojos del Salado: This is the highest active volcano in the world, sitting right on the border between Chile and Argentina.

- Huascarán: The crown of the Peruvian Andes, which is legendary among climbers and sits within a stunning national park.

The range is also home to Lake Titicaca, which straddles the border of Peru and Bolivia. It's the highest navigable lake in the world. You’ll find it sitting in a massive basin right in the middle of the mountains. If you’re looking at a map, it’s that blue thumbprint right in the center of the widest part of the range.

The human element: Living on the edge

Kinda crazy to think about, but millions of people live at altitudes that would make most of us pass out from oxygen deprivation. Cities like La Paz, Quito, and Bogotá aren't just "near" the mountains; they are in them.

👉 See also: Getting to Burning Man: What You Actually Need to Know About the Journey

La Paz, for instance, is tucked into a bowl-shaped canyon at over 11,000 feet. Living there means your car has to handle some of the steepest inclines you've ever seen. The Inca Empire, one of the most sophisticated civilizations in history, was built entirely within the folds of these peaks. They figured out how to farm on vertical slopes using terraces, a practice you can still see today at places like Machu Picchu.

The geography forced people to be incredibly resilient. Even today, the "Andean" identity is a very real thing. It’s a blend of indigenous traditions and the reality of surviving in a landscape that is beautiful but often harsh.

How to use a map to plan a visit

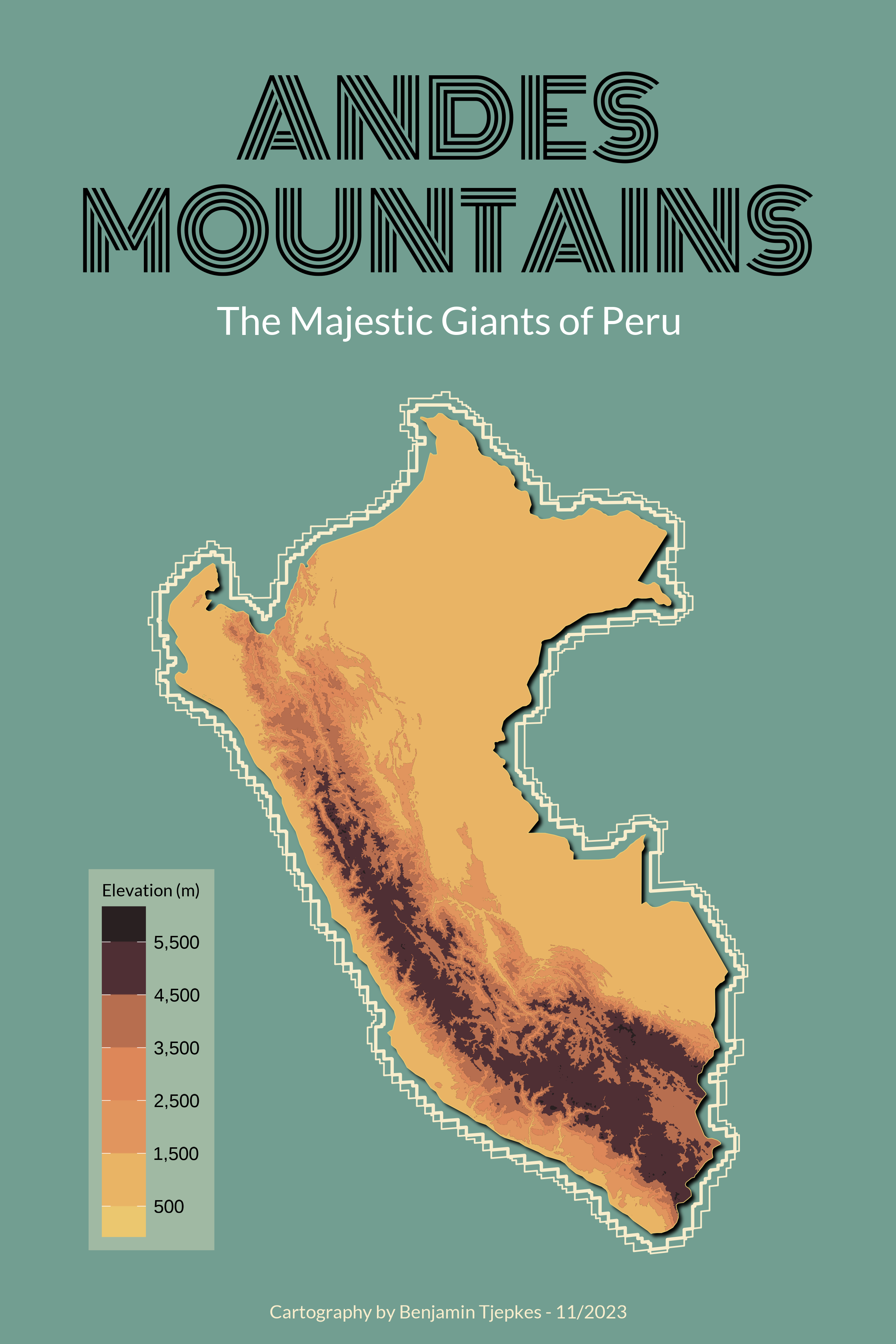

If you’re trying to visualize where to go, don’t just look at the country. Look at the elevation shading.

The most accessible parts for travelers are usually through major hubs like Cusco (for the Sacred Valley) or Santiago (for the central Chilean Andes). If you want the dramatic, jagged peaks that look like something out of a fantasy novel, you head south to Patagonia. Places like Torres del Paine in Chile and Los Glaciares National Park in Argentina are where the Andes meet the end of the world.

Getting around isn't always easy. Because the range is so steep and rugged, roads are often narrow and winding. The "Death Road" in Bolivia is a famous (and terrifying) example of what happens when humans try to carve paths through this vertical world.

Modern mapping and the Andes

Today, we use satellite imagery to track how the Andes are changing. Climate change is hitting these mountains hard. The glaciers in the tropical Andes—mostly in Peru—are retreating at an alarming rate. This is a big deal because those glaciers provide the water for millions of people. When the ice disappears, the water source for the valleys below disappears too.

✨ Don't miss: Tiempo en East Hampton NY: What the Forecast Won't Tell You About Your Trip

Mapping the Andes isn't just about drawing lines anymore; it's about monitoring the health of the snowpack. Organizations like the Andean Community and various geological surveys use GPS and LIDAR to see exactly how much these mountains are shifting.

Actionable steps for finding your way

If you are currently looking at a map and trying to navigate this region, here is how you should approach it:

First, distinguish between the Altiplano and the Coastal Ranges. If you are heading into the Altiplano (Bolivia/Peru), you need to pack for intense sun and freezing nights. The altitude is no joke.

Second, check the seasonal differences. Because the Andes span such a huge latitude, "winter" in the Colombian Andes (near the equator) is just a rainy season, whereas winter in the Southern Andes (Patagonia) means heavy snow and impassable roads from June to August.

Third, use topographic layers on Google Maps or OpenStreetMap. Standard street views won't show you the reality of the terrain. Switch to "Terrain" or "Satellite" to understand the ridges and valleys. This is crucial if you're planning on hiking or driving between cities.

Lastly, respect the Passes. If you're driving from Mendoza, Argentina, to Santiago, Chile, you're crossing the "Cristo Redentor" pass. It’s one of the few reliable ways over the massive wall, and it can close in a heartbeat due to weather. Always have a backup plan when traveling through these coordinates.

The Andes are more than just a location on a map; they are a living, breathing barrier that dictates the life of an entire continent. Whether you're looking at them from a satellite or standing at the base of a 20,000-foot peak, their scale is almost impossible to wrap your head around.