You’re doing it right now. As you read this sentence, your body is performing a high-stakes chemical swap. It’s silent. It’s automatic. Honestly, most of us never give it a second thought until we’re out of breath running for a bus or dealing with a nasty bout of bronchitis. But if you've ever stopped to wonder where does the exchange of gases take place, the answer isn't just "the lungs." That's too vague. The real magic happens in a microscopic world that looks remarkably like a bunch of grapes.

We’re talking about the alveoli. These are teeny-tiny air sacs tucked deep inside your lungs, right at the very end of the respiratory tree. They are the frontline. Without them, the oxygen you inhale would just sit in your chest with nowhere to go, and the carbon dioxide building up in your blood would eventually become toxic.

The Microscopic Hub: How Alveoli Work

So, let's get specific. Your lungs contain roughly 480 million of these little sacs. If you were to spread them all out flat, they’d cover about half a tennis court. That massive surface area is intentional. Evolution figured out that to power a big, hungry human brain and moving muscles, we needed a massive "loading dock" for oxygen.

When you breathe in, air travels down your trachea, splits into the bronchi, then into smaller bronchioles, and finally lands in the alveoli. This is exactly where the exchange of gases takes place through a process called passive diffusion. It’s not forced. It’s just physics.

Think of it like a crowded room. If one room (your lungs) is packed with oxygen molecules and the neighboring room (your blood capillaries) is empty, the oxygen is naturally going to push through the "wall" to balance things out.

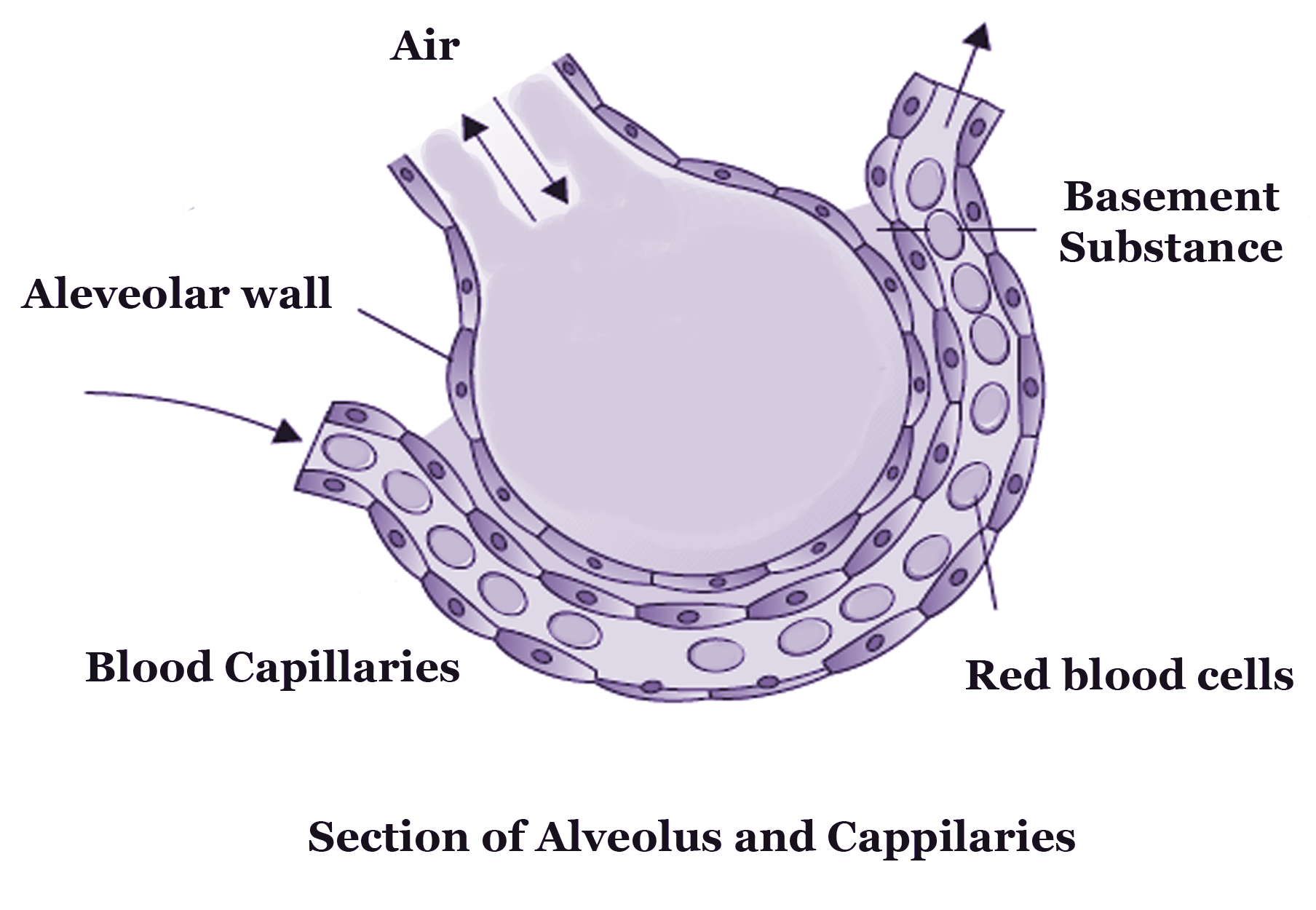

The Blood-Air Barrier

The "wall" I’m talking about is the respiratory membrane. It is incredibly thin—we're talking about two cells thick. One cell belongs to the wall of the alveolus, and the other belongs to the capillary wrapped around it. They are fused together. This thinness is vital because gases have to move fast. If that membrane thickens due to inflammation or fluid, you start feeling "short of breath." This is why conditions like pneumonia or pulmonary edema are so dangerous; they literally put a barrier between the air and your blood.

👉 See also: Cleveland clinic abu dhabi photos: Why This Hospital Looks More Like a Museum

Why Does Oxygen Move at All?

It comes down to partial pressure. This is a nerdy way of saying "concentration." Inside the alveoli, the partial pressure of oxygen is high. In the blood returning from your body—which has already "dropped off" its oxygen to your toes and liver—the pressure is low.

- Oxygen moves from the air sac into the blood.

- It hitches a ride on a protein called hemoglobin inside your red blood cells.

- Simultaneously, carbon dioxide (the waste product) moves from the blood into the air sac to be exhaled.

It’s a two-way street. A constant, rhythmic trade.

The Role of Hemoglobin: The Oxygen Taxi

While the alveoli are the location, hemoglobin is the vehicle. Dr. Linus Pauling, a giant in the world of molecular biology, spent years studying how this protein changes shape just to grab and release oxygen at exactly the right moment. When the blood is in the lungs, hemoglobin has a high "affinity" for oxygen. It wants it. It grabs it. But when that blood reaches a working muscle that’s hot and acidic from exercise, the hemoglobin "relaxes" and lets the oxygen go.

If your iron levels are low—a condition known as anemia—you have fewer "taxis" available. You might be breathing perfectly fine, and your alveoli might be healthy, but you’ll still feel exhausted because the transport system is broken.

What Happens When Things Go Wrong?

We often take for granted where the exchange of gases takes place until that specific real estate gets damaged. Smoking is the most obvious culprit. It doesn't just "dirty" the lungs; it actually destroys the walls of the alveoli. This is emphysema. Instead of hundreds of tiny, efficient bubbles, you end up with a few large, saggy bags. Less surface area equals less oxygen in your blood. You can gasp for air all day, but if the exchange site is gone, the air can't get in.

✨ Don't miss: Baldwin Building Rochester Minnesota: What Most People Get Wrong

Then there’s the issue of surfactants. These are fatty substances that coat the inside of the alveoli. Without surfactant, the surface tension of the water inside your lungs would cause the tiny sacs to collapse every time you exhale. It would be like trying to blow up a wet balloon that’s stuck together. This is a major hurdle for premature babies, whose bodies haven't started making enough surfactant yet, leading to Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS).

Real-World Impact: Altitude and Exercise

Have you ever been to Denver or the Swiss Alps and felt like you couldn't catch your breath? The location of gas exchange hasn't changed, but the physics has. At high altitudes, the "pressure" of oxygen in the atmosphere is lower. Remember that "crowded room" analogy? At 10,000 feet, the room isn't as crowded. There’s less pressure pushing the oxygen across that thin membrane into your blood.

Your body compensates by:

- Breathing faster to bring in more "tries" at the exchange.

- Increasing your heart rate to move the "taxis" (red blood cells) faster.

- Eventually, making more red blood cells (which is why athletes train at high altitudes).

On the flip side, during intense exercise, your muscles are screaming for O2 and dumping CO2 into the blood. The gradient—the difference in pressure—becomes much steeper. This actually makes the exchange more efficient in a healthy person, as the "empty" blood arriving at the lungs is even thirstier for oxygen than usual.

Beyond the Lungs: Internal Respiration

Technically, there’s a second place where gas exchange happens. Scientists call this "internal respiration." While the lungs handle the external exchange (air to blood), the same process happens again at every single cell in your body.

🔗 Read more: How to Use Kegel Balls: What Most People Get Wrong About Pelvic Floor Training

In your bicep, your brain, and your gut, the blood drops off oxygen and picks up CO2. It’s the same physics, just in reverse. If the alveoli are the "import/export dock," the systemic capillaries in your body are the "delivery trucks" unloading at the warehouse.

Improving Your Gas Exchange Efficiency

You can't exactly grow more alveoli as an adult, but you can certainly make the ones you have work better. It’s mostly about protecting the membrane and the pump.

- Hydration is non-negotiable. The mucus membranes in your respiratory tract need to stay moist to trap irritants before they reach the delicate alveoli.

- Cardiovascular exercise strengthens the heart, ensuring that blood moves through the lung capillaries at an optimal rate—not too fast that it misses the exchange, and not too slow that it stalls.

- Air quality matters. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is small enough to travel all the way down into the air sacs, causing scarring over time. Using HEPA filters in high-pollution areas isn't just a luxury; it’s maintenance for your exchange sites.

The complexity of this system is honestly staggering. That two-cell-thick barrier is all that stands between life and... well, not life. It's a delicate, beautiful piece of biological engineering that works perfectly for most of us, most of the time.

Next Steps for Lung Health

To get a better sense of how well your specific gas exchange is working, you can start with a few simple observations. Monitor your "recovery time" after a flight of stairs; a healthy exchange system should return your breathing to a normal rhythm within a minute or two. If you're curious about the numbers, a pulse oximeter—a tiny device that clips onto your finger—can give you a real-time look at your oxygen saturation ($SpO_2$). Most healthy people should sit between 95% and 100%. If you consistently see lower numbers or feel chronic shortness of breath, it’s worth asking a doctor about a spirometry test to check your lung function and ensure your alveoli are doing their job.