Tornadoes are terrifying. If you’ve ever stood in a flat field in Kansas and watched the sky turn that bruised, sickly shade of green, you know exactly what I’m talking about. Most of us grew up believing that these monsters only live in one specific place. We call it Tornado Alley. We picture dusty farms, storm chasers in reinforced trucks, and Dorothy’s house spinning into the atmosphere. But if you're looking at a map from twenty years ago to figure out where do tornadoes occur, you're looking at outdated information. The geography of fear is shifting.

It’s not just about the Great Plains anymore.

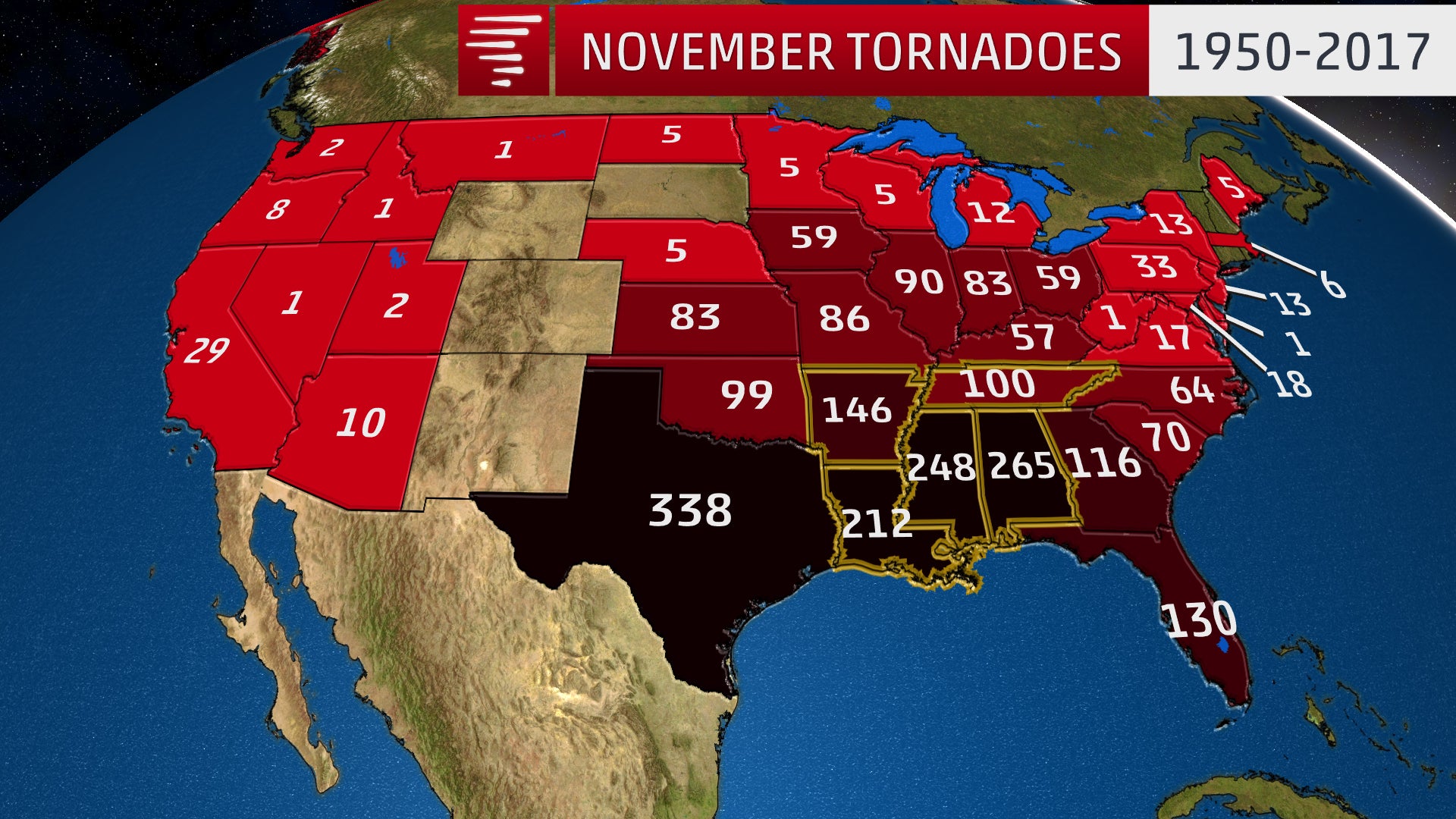

Lately, the "where" has become just as important as the "when." While the central United States remains the global capital for twisters, the bullseye is migrating. It’s sliding east. It’s creeping into the deep woods of Mississippi and the valleys of Tennessee. This isn't just a minor statistical fluke; it’s a fundamental shift in how atmospheric energy is distributed across the North American continent.

The Classic Blueprint: Why the U.S. is the Unlucky Winner

To understand where do tornadoes occur, you have to look at the unique, almost cruel, geography of North America. We have the Rocky Mountains to the west. We have the Gulf of Mexico to the south. And we have cold, dry air screaming down from Canada.

When these three ingredients collide, it’s like a chemical reaction that can't be stopped. The warm, moist air from the Gulf acts as fuel. The dry air from the Rockies acts as a cap, holding that energy down until it builds up enough pressure to explode upward. This creates supercells. Supercells create tornadoes.

Now, compare this to Europe. Europe has the Alps, but they run east-to-west. This blocks the easy mixing of polar and tropical air masses. In South America, the Andes are massive, but the landmass is narrower, which limits how much "fuel" can gather in one spot. Australia gets them, sure, but they’re mostly in sparsely populated areas. The U.S. gets about 1,200 tornadoes a year. That is more than any other country on Earth, and it’s not even close.

The Rise of Dixie Alley

For a long time, the spotlight stayed on Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. That’s the traditional Tornado Alley. But researchers like Victor Gensini from Northern Illinois University have been pointing out a disturbing trend: tornado frequency is dropping in the Plains and spiking in the Southeast.

📖 Related: Casualties Vietnam War US: The Raw Numbers and the Stories They Don't Tell You

They call it Dixie Alley.

This isn't just a change in location; it’s a change in lethality. In Oklahoma, you can see a tornado coming from miles away. The horizon is wide. In Alabama or Mississippi, you have hills. You have thick pine forests. You have high humidity that "wraps" tornadoes in rain, making them invisible until they are literally on top of your house.

Furthermore, the Southeast is more densely populated. There are more mobile homes, which are notoriously vulnerable to high winds. If a tornado hits an empty wheat field in South Dakota, it’s a weather event. If it hits a suburb in Birmingham at 2:00 AM, it’s a mass casualty event.

The data suggests that since the late 1970s, tornado activity in the Southeast has increased significantly. We’re talking about states like:

- Mississippi

- Alabama

- Tennessee

- Kentucky

- Arkansas

Honestly, the term "Tornado Alley" is becoming a bit of a misnomer. It’s more like a "Tornado Region" that covers nearly the entire eastern half of the country.

Can They Happen Anywhere?

Yes. Basically.

👉 See also: Carlos De Castro Pretelt: The Army Vet Challenging Arlington's Status Quo

People used to say tornadoes couldn’t cross rivers. They said they couldn’t go over mountains. They said downtown areas were safe because the skyscrapers would "break up" the wind. All of that is nonsense.

In 1999, a tornado ripped through downtown Salt Lake City. That’s in the shadows of the Wasatch Range. In 1987, a massive F4 tornado crossed the Continental Divide in Yellowstone National Park, climbing over 10,000 feet. The idea that terrain protects you is a dangerous myth. If the atmospheric conditions—the shear, the lift, the instability—are there, a tornado will happen.

Even outside the U.S., there are hotspots that would surprise you. Bangladesh is actually the deadliest place for tornadoes outside of North America. They don't get as many as we do, but their population density is so high and their housing is so fragile that a single storm can kill hundreds. The United Kingdom actually has the highest number of tornadoes per square mile of any country, but they are usually weak "landspouts" that barely knock over a garden fence.

The Seasonality Factor: It's Not Just May Anymore

When we talk about where do tornadoes occur, we also have to talk about when. The "peak" is traditionally April, May, and June. This is when the temperature contrast between the seasons is the most violent.

But we are seeing more "off-season" outbreaks. Look at December 2021. A devastating tornado tracked over 160 miles through Arkansas, Missouri, Tennessee, and Kentucky. It happened in the middle of the night, in the middle of winter.

This is where the climate conversation gets tricky. While it’s hard to say "climate change causes this specific tornado," scientists are seeing that the environment for tornadoes is becoming more common in the winter months. Warmer winters mean more moisture in the air. More moisture means more fuel. If a cold front sweeps through in January and hits 70-degree air in Kentucky, the atmosphere doesn't care that it's winter. It's going to react.

✨ Don't miss: Blanket Primary Explained: Why This Voting System Is So Controversial

Practical Steps for the New Reality

Since the map is changing, your preparation has to change too. It doesn't matter if you live in a "traditional" high-risk zone or not.

Invest in a NOAA Weather Radio. This is the only thing that will reliably wake you up at 3:00 AM when your phone is on "Do Not Disturb" or the cell towers are down. It’s old-school tech, but it saves lives.

Know your "Safe Room." If you don't have a basement, you need an interior room on the lowest floor with no windows. A bathroom or a closet. Most people who die in tornadoes aren't "blown away"—they are hit by flying debris. Putting as many walls as possible between you and the outside is the goal.

Stop relying on sirens. Sirens are designed for people who are outdoors. They are not meant to be heard inside a modern, insulated house. If you are waiting for a siren to tell you to move, you’re already behind the curve.

Check your local geography. If you live in the Southeast, be aware of "nocturnal tornadoes." These are far more common in Dixie Alley than in the Plains. Have a plan that works in the dark.

The geography of where do tornadoes occur is no longer a static map in a textbook. It's a fluid, shifting reality. Whether you’re in the heart of Oklahoma or the suburbs of Pennsylvania, the atmosphere is capable of surprises. Understanding that the "Alley" has moved is the first step in staying ahead of the storm. Stay weather-aware, keep your boots near the bed during a watch, and never assume your zip code makes you immune.