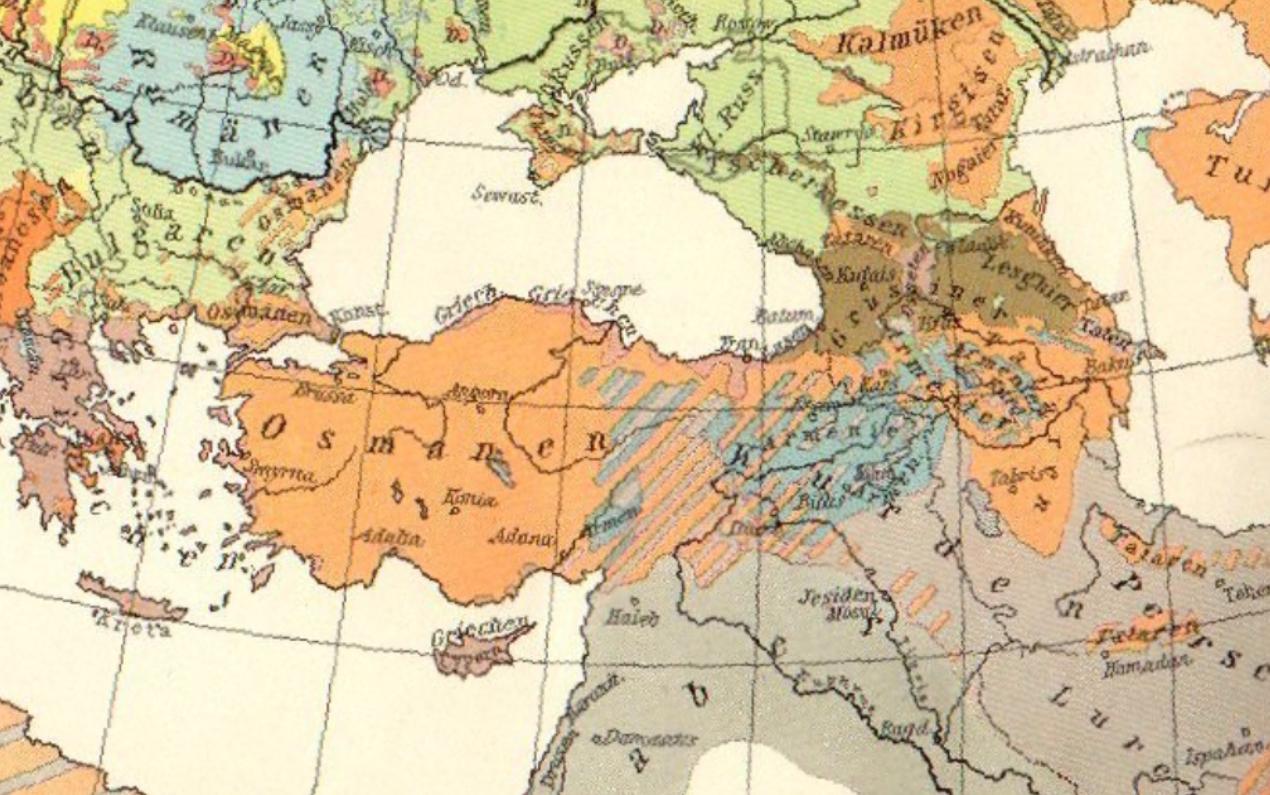

It’s a question that sounds simple on the surface but gets incredibly heavy once you look at a map. Honestly, when people ask where did the Armenian genocide take place, they usually expect a single city or a specific border. The reality is much more sprawling and, frankly, terrifying. We aren't just talking about one spot; we're talking about the systematic uprooting of an entire population across the vast territory of the Ottoman Empire.

It happened everywhere.

From the sophisticated streets of Constantinople to the scorching, desolate sands of the Syrian Desert, the geography of this atrocity covered thousands of miles. It was a logistical nightmare turned into a human one. If you look at a map of the Middle East today, you're looking at the graveyard of a civilization that had been there for three thousand years.

The Starting Point: Why Constantinople Was First

The whole thing kicked off in what is now Istanbul. Back then, it was Constantinople. On April 24, 1915—a date Armenians still commemorate every year—the Ottoman authorities rounded up hundreds of Armenian intellectuals, politicians, and artists. They didn't start in the villages. They started with the brain trust.

They took these people from their homes in the middle of the night. Most were sent to holding centers in Central Anatolia, like Ayash and Chankiri. Very few ever came back. By hitting the capital first, the "Young Turk" government (the Committee of Union and Progress) effectively decapitated the Armenian community. It made organized resistance almost impossible. Imagine if every leader in your city just vanished overnight. That’s how it started.

The Heart of the Horror: The Six Provinces

To really understand where did the Armenian genocide take place, you have to look at the "Six Vilayets." These were the heartland provinces of Western Armenia within the Ottoman Empire: Van, Erzurum, Mamuret-ul-Aziz (Harput), Bitlis, Sivas, and Diyarbekir.

This wasn't some distant "war zone" issue. This was neighbor turning on neighbor. In places like Van, there was actually a period of armed resistance because the locals saw the writing on the wall. But in most other provinces, the process was chillingly bureaucratic. The government would issue "Techir" (deportation) laws. They told families they were being moved for their own safety because of the ongoing World War I.

They weren't.

The men were often separated immediately. In many villages, they were marched just outside the town limits and executed in valleys or near riverbeds. The women, children, and elderly were then forced onto "death marches." If you’re wondering about the specific terrain, think of the Anatolian plateau. It’s rugged. It’s mountainous. In the winter, it’s brutally cold; in the summer, it’s a furnace. People were forced to walk for weeks without food or water.

The Euphrates River: A Moving Grave

Rivers play a huge role in this geography. The Euphrates, specifically. It became a dumping ground. Diplomats from other countries—like the American Consul Leslie Davis, who was stationed in Harput—wrote harrowing reports about what they saw. Davis actually went out on horseback to see the "slaughterhouse province" for himself. He described valleys filled with thousands of bodies. He wasn't exaggerating.

The geography of the genocide followed the water. If you were an Armenian being marched south, the river was often your only source of water, but it was also where the "Special Organization" (Teskilat-i Mahsusa) units would wait. These were often groups of released convicts or irregular tribesmen tasked with the "wet work" the regular army didn't want to do.

The End of the Line: Deir ez-Zor

If you survived the mountains and the rivers, you ended up in the desert. Specifically, the Syrian Desert. The town of Deir ez-Zor became synonymous with the final stage of the genocide.

It was basically a concentration camp without walls.

There was nothing there. No shelter. No rations. Just the sun. By the time the caravans reached the desert, the people were "living skeletons," according to eyewitness accounts from German and Swiss missionaries. The governors of these desert regions were often replaced if they showed too much mercy. The ones who stayed in power were the ones who ensured that "deportation" meant "extinction."

💡 You might also like: What Most People Get Wrong About Imperial Courts Los Angeles

The Regional Impact Beyond Turkey

We often focus on modern-day Turkey, but the scope was wider. It bled into Persia (modern-day Iran). During the Ottoman retreat and advance through the Caucasus, Armenian villages in Northwestern Iran, like those around Urmia and Salmas, were targeted too.

Then there are the "orphanages." In places like Lebanon (which was then part of Greater Syria), the remnants of the Armenian population gathered. The Antoura orphanage is a famous—and tragic—example. It was a place where Armenian children were "Turkified," forced to take Muslim names and abandon their language. So, the "where" isn't just a physical location on a map; it was also the interior space of a child's identity.

Why the Geography Matters for SEO and History

When researchers look for where did the Armenian genocide take place, they often find that the physical evidence is being erased. Ancient churches in Eastern Turkey are often in ruins or repurposed as barns. Some towns have been renamed. This isn't just a quirk of history; it’s a conscious effort to change the map.

But you can't erase the geography of the soil. Mass graves are still being found. The layout of the railway lines—the Baghdad Railway—shows how the Ottoman state used modern infrastructure to move people toward their deaths. It was a very "modern" genocide in that sense. It used trains, telegraphs, and a centralized bureaucracy.

💡 You might also like: Winning Powerball Numbers South Carolina: What Most People Get Wrong

Misconceptions About the Location

A lot of people think this happened in a vacuum or only in the "wild" East. Nope. It happened in Smyrna (modern Izmir) on the coast. It happened in Adana. It happened in the beautiful mountainous regions of Cilicia.

Some think it was just a byproduct of "war chaos." But the locations tell a different story. If it was just war, why were people being marched away from the front lines toward the desert? Why were the locations of the massacres so far removed from the Russian border? The geography proves the intent. You don't march a grandmother from a lush mountain village to a barren desert because of "military necessity." You do it to make sure she doesn't come back.

Actionable Steps for Further Learning

If you want to dig deeper into the physical reality of this history, there are ways to do it that go beyond just reading a Wikipedia page.

- Consult the Houshamadyan Project: This is an incredible digital archive that reconstructs Armenian life in the Ottoman Empire town by town. It’s the best way to see what these places looked like before the 1915-1923 period.

- Study the "Blue Book": Officially known as The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, 1915–1916, this is a collection of eyewitness reports compiled by Viscount Bryce and Arnold Toynbee. It lists specific locations, dates, and names. It’s dry, legalistic, and utterly devastating.

- Visit the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute (Online or in Yerevan): Their maps are some of the most detailed in the world. They show the deportation routes, the locations of the concentration camps, and the sites of major massacres.

- Read "The Burning Tigris" by Peter Balakian: This book does a great job of explaining the American response and the specific locations where U.S. diplomats witnessed the events.

- Look at Satellite Imagery: If you’re tech-savvy, you can use Google Earth to find the ruins of Armenian monasteries like Sourp Barasuma or the Cathedral of Arapgir. Seeing the "footprint" of what's missing is a powerful way to understand the scale.

The geography of the Armenian genocide is a map of a world that no longer exists. Understanding that it took place in the very heart of what we now call the Middle East is vital. It wasn't on the fringes. It was everywhere. Recognizing these locations is the first step in ensuring that the history of the people who lived there isn't completely wiped off the map.