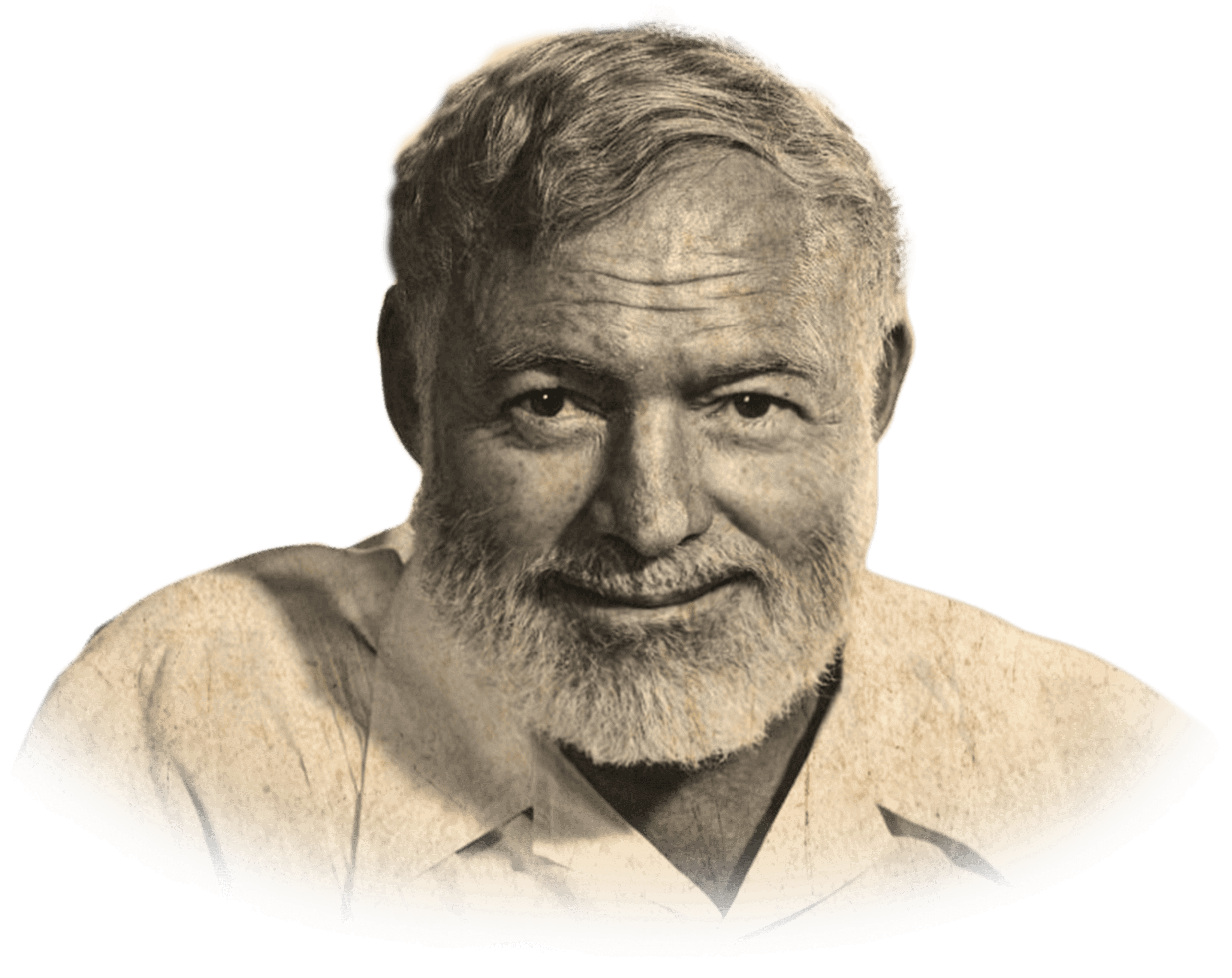

You’ve probably seen the photos. A bearded man in a safari jacket, squinting at the sun, maybe holding a glass of something strong or a very large fish. Ernest Hemingway is the ultimate "peripatetic" writer—a fancy way of saying the guy couldn't sit still.

If you ask a casual fan where did Ernest Hemingway live, they’ll usually shout "Key West!" or "Cuba!" and call it a day. Honestly, they aren't wrong, but they’re missing about 80% of the map. Hemingway didn't just live in those places; he haunted them. He moved because of wars, because of wives (he had four, so that was a lot of packing), and because he was constantly chasing a version of "the good life" that seemed to keep shifting over the next horizon.

From a Victorian bedroom in Illinois to a concrete "bunker" in the Idaho woods, his homes were never just addresses. They were his writing labs.

The "Endless Victorian" Childhood in Oak Park

Hemingway was born in 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois. He famously called it a place of "wide lawns and narrow minds." Kinda harsh, right? But it tells you everything about why he spent the rest of his life running toward danger and dirt.

He spent his first six years in a grand Queen Anne-style house at 339 North Oak Park Avenue. It was his maternal grandparents' place, and it was fancy for the time. It was actually the first house in the neighborhood to have electricity. His mother, Grace, was an opera singer who gave lessons in the parlor, and his father, Clarence, was a doctor who kept wildlife specimens on the top floor. It was a house of high culture and taxidermy.

Later, the family moved to a "Prairie-style" home at 600 North Kenilworth Avenue. This is where "young Ernest" became the guy we recognize—the high school football player and the aspiring reporter. But the place that actually mattered to him wasn't in Oak Park at all. It was the family summer cottage, Windemere, on Walloon Lake in Michigan. That’s where he learned to hunt and fish, the two things that arguably defined his public persona more than his Nobel Prize ever did.

Paris: Hunger, Luck, and Shabby Apartments

When people romanticize Hemingway, they’re usually thinking of the 1920s. The "Lost Generation." After getting blown up in WWI as an ambulance driver in Italy (where he stayed in various military hospitals, obviously not "homes"), he landed in Paris with his first wife, Hadley Richardson.

👉 See also: Weather at Lake Charles Explained: Why It Is More Than Just Humidity

They lived at 74 rue du Cardinal Lemoine in the Latin Quarter. It was a dump. Seriously. No hot water, no indoor toilet—just a mattress on the floor and a bucket. He wrote about it in A Moveable Feast, mentioning how you could see the coal man from the window. He didn't write at home much because it was too cold and cramped. Instead, he’d trek over to cafes like Les Deux Magots or the Closerie des Lilas to work over a single café au lait.

As he got more famous (and slightly less broke), he moved.

- 113 rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs: Near the Luxembourg Gardens.

- 6 rue Férou: This was during the transition to his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer.

Paris wasn't about the real estate for him. It was about the proximity to Sylvia Beach’s bookstore, Shakespeare and Company, and the ability to be "poor but happy." Or so he claimed later, through a very thick lens of nostalgia.

The Key West Years: Cats, Urinals, and Chaos

In 1931, Hemingway’s second wife's wealthy uncle bought them a house at 907 Whitehead Street in Key West. It cost $8,000 at the time. Today? That property is worth millions.

This is the house everyone knows. The limestone walls are 18 inches thick to survive hurricanes. It’s where the "Hemingway cats"—those six-toed (polydactyl) felines—started their dynasty. Interestingly, Hemingway didn't actually have many cats in Key West; he mostly had peacocks. The cat obsession really ramped up later in Cuba, though a sea captain did famously gift him a six-toed cat named Snow White in Florida.

The Pool Controversy

While Hemingway was away reporting on the Spanish Civil War, Pauline decided to build a swimming pool. It was the first in-ground pool in Key West and cost a staggering $20,000—more than double what they paid for the whole house. When Ernest got back and saw the bill, he reportedly took a penny out of his pocket, pressed it into the wet cement, and told Pauline she’d taken his last cent. You can still see that penny there today.

✨ Don't miss: Entry Into Dominican Republic: What Most People Get Wrong

He wrote To Have and Have Not here, and Green Hills of Africa. But the "Key West Mob" (his group of drinking buddies) and the fame started to grate on him. He needed a new escape.

Finca Vigía: The Cuban Sanctuary

If you really want to know where Ernest Hemingway lived the longest, it’s Cuba. He spent 20 years at Finca Vigía (Lookout Farm) in San Francisco de Paula, about 15 miles outside Havana.

He moved there in 1939 with his third wife, Martha Gellhorn. She’s actually the one who found the place because she was sick of living in his cramped room at the Hotel Ambos Mundos in downtown Havana. He eventually bought the finca in 1940 for $12,500.

This was his "true" home. It had:

- Thousands of books (he was a massive hoarder of print).

- His boat, the Pilar, docked nearby in Cojímar.

- A literal tower Mary Welsh (wife #4) built for him to write in, though he mostly just used it to store his gear and wrote in his bedroom instead.

He lived here through the Cuban Revolution. He actually got along okay with Fidel Castro—there's a famous photo of them shaking hands at a fishing tournament. But as the political tension between the US and Cuba boiled over, and his own health started to fail, he was basically forced to leave in 1960. He left everything behind: his clothes, his manuscripts, his half-drunk bottles of booze. It’s still a museum today, looking exactly like he just stepped out for a walk.

The Final Chapter: Ketchum, Idaho

Most people don't realize Hemingway ended up in the mountains. He had been visiting Sun Valley since 1939, often staying for free at the Sun Valley Lodge (Room 206) because the owners wanted the celebrity "clout" of having him there.

🔗 Read more: Novotel Perth Adelaide Terrace: What Most People Get Wrong

In 1959, he bought a house at 400 Northwood Way in Ketchum. Unlike the tropical villas or the Parisian flats, this was a mid-century modern house made of "faux-wood" concrete. It looked like a fortress. He chose it because the air was dry—good for his papers—and it was secluded.

It’s a bit of a somber place. This is where he struggled with severe depression and paranoia, undergoing electroshock therapy at the Mayo Clinic before returning to the house. It was here, in the foyer, that he took his own life on July 2, 1961.

Summary of Hemingway's Main Residences

| Period | Location | Key Work Written There |

|---|---|---|

| 1899–1917 | Oak Park, IL | Early journalism / Nick Adams stories (inspiration) |

| 1921–1926 | Paris, France | The Sun Also Rises |

| 1931–1939 | Key West, FL | A Farewell to Arms (finished here), To Have and Have Not |

| 1939–1960 | Havana, Cuba | The Old Man and the Sea, For Whom the Bell Tolls |

| 1959–1961 | Ketchum, ID | A Moveable Feast (editing/refining) |

Why His Homes Matter Today

Where Hemingway lived wasn't just about a roof over his head. He was a "place" writer. If he was writing about the Gulf Stream, he needed to smell the salt. If he was writing about the bullrings in Spain, he was living in hotels in Madrid.

Actionable Insights for Literary Travelers:

- Visit Key West first: It’s the most "accessible" and has the best tour-guide stories (and the cats).

- Don't try to visit the Idaho house: It’s owned by a library and isn't open to the public; it’s a residence for writers now. You can see his grave in the Ketchum Cemetery, though.

- Cuba is the "Holy Grail": It’s harder to get to for Americans, but Finca Vigía is the most "authentic" because he didn't have time to pack his stuff before he left.

- Check out the "Nick Adams" country: If you want to see what made him a writer, go to Walloon Lake in Michigan. It’s still as beautiful as he described.

Hemingway once said, "In order to write about life first you must live it." He certainly didn't do that from a cubicle. He did it from some of the most beautiful, rugged, and sometimes broken houses in the world.

To truly understand his work, start by looking at his geography. Pick one of his "home" cities for your next trip and read the book he wrote there while you're on the ground. There is no better way to see the world through "Papa’s" eyes.