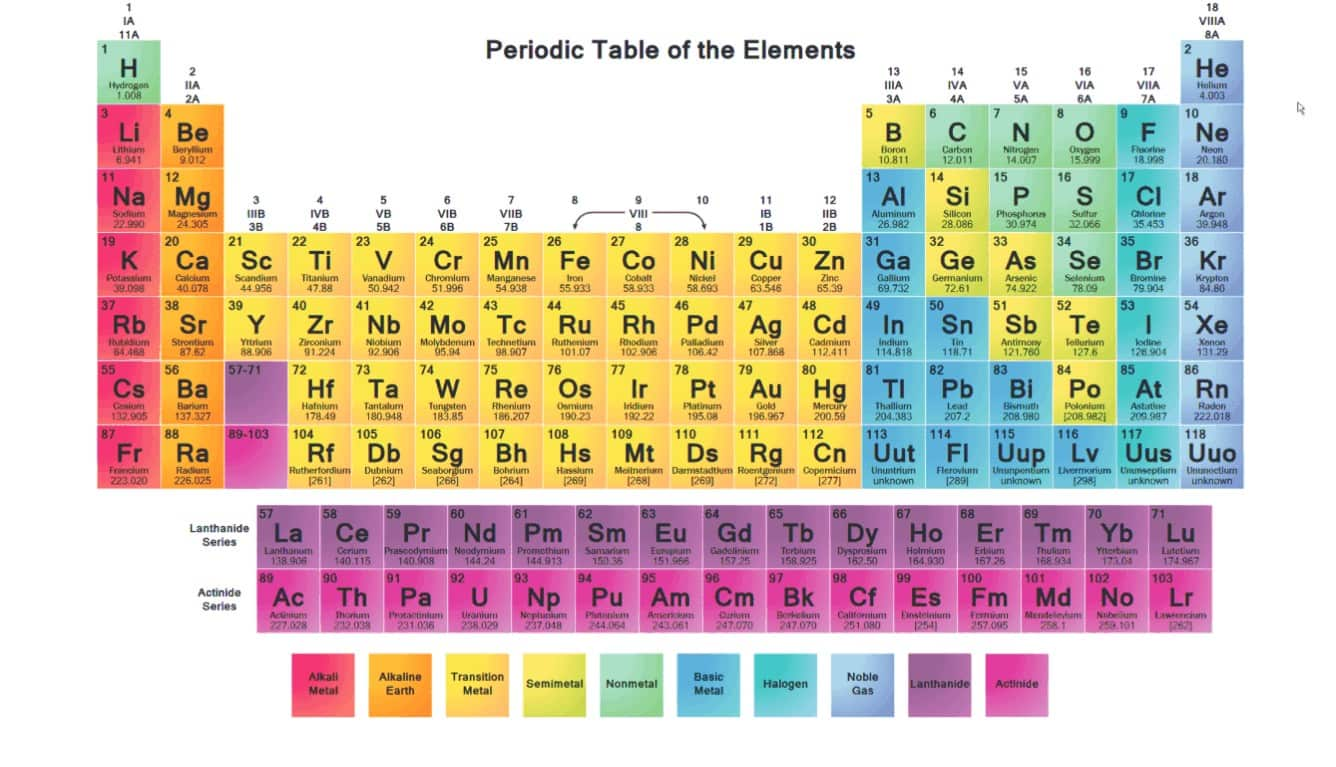

You’re looking at a periodic table. It’s huge. Honestly, it’s a bit overwhelming with all those letters and numbers, but if you look at the very first column on the left, you’ve found them. That’s it. That’s where the alkali metals are located in the periodic table. They sit right there in Group 1. It’s a vertical strip of elements that includes Lithium, Sodium, Potassium, Rubidium, Cesium, and Francium.

But wait. Look closer. You'll see Hydrogen sitting at the very top of that column. Is it an alkali metal? Nope. Not even close. Even though Hydrogen shares that prime real estate in Group 1, it’s a nonmetal gas. It’s basically a squatter in that column because it has one valence electron, just like the actual metals below it. Real alkali metals are shiny, soft, and so reactive they’ll literally explode if you drop them in a bucket of water.

The Column One Crowd: Breaking Down the Neighbors

If you want to be precise, where the alkali metals are located in the periodic table is the s-block. This isn't just a random spot. Nature likes patterns. These elements all have a single electron in their outermost shell ($ns^1$). Because that lone electron is just hanging out there, it’s incredibly easy to lose. This makes them the "divas" of the chemical world—they can't stand being alone and are always looking to bond with someone else.

Lithium (Li) starts the party at atomic number 3. Then you move down to Sodium (Na), which most of us eat every day in salt. Below that is Potassium (K). If you keep going down, things get weird and a bit dangerous. Rubidium (Rb), Cesium (Cs), and the incredibly rare Francium (Fr) round out the bottom.

Why the Left Side Matters

Placement is everything in chemistry. The reason they are on the far left is that they have the largest atomic radii in their respective periods. They are big, relatively speaking, and their hold on that outer electron is weak.

As you move down the column, the distance between the nucleus and that outer electron grows. This is why a chunk of Lithium might just fizzle and smoke in water, but Cesium will basically blow your lab equipment apart. The further down the column you go, the more "eager" the metal is to get rid of that electron.

Beyond the Basics: What Everyone Gets Wrong

Most people think "metal" and imagine something hard like a steel beam or a copper pipe. Alkali metals laugh at that. You can cut Sodium with a butter knife. It feels kinda like cold beeswax. If you tried to build a bridge out of these, it would melt the first time it rained, and the bridge would technically disappear into a cloud of caustic smoke and fire.

They are never found sitting around in nature by themselves. You won't go hiking and find a nugget of pure Potassium. They are always "married" to something else, usually salts or minerals.

The Hydrogen Confusion

Let’s talk about the Hydrogen elephant in the room again. It is physically located in Group 1, but it is excluded from the alkali metal family. Why? Because under normal Earth conditions, it doesn’t act like a metal. However, some physicists, like those at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, have actually turned Hydrogen into a liquid metal under insane amounts of pressure—like the kind you’d find in the core of Jupiter. But for your chemistry test or general knowledge, Hydrogen is just a neighbor, not a family member.

The Reactive Nature of Group 1

Since you know where the alkali metals are located in the periodic table, you should know why that location makes them so reactive. Since they are at the start of each period (row), they are beginning a new electron shell.

Take Sodium. It has 11 electrons. Two in the first shell, eight in the second (which is a "full house"), and then just one lonely electron in the third shell. That one electron is the problem. Sodium desperately wants to get back to that stable "eight" count. To do that, it just gives the one electron away to someone like Chlorine. Boom. You have Sodium Chloride. Table salt. Stable. Delicious on fries.

Atomic Trends Down the Column

- Ionization Energy: This is the energy needed to kick that electron out. It decreases as you move down. It's much easier to steal an electron from Cesium than from Lithium.

- Melting Points: These actually go down as you move down the group. Cesium will almost melt in your hand on a hot day (though please don't touch it, it’s toxic and reactive).

- Density: Generally, they get denser as you go down, but they are all remarkably light. Lithium is actually the least dense solid element. It would float on oil.

Real World Jobs for Group 1 Elements

These elements aren't just science fair explosions. They run our world.

Lithium is the heart of your phone battery. It’s light and holds a charge well. Sodium vapor lamps give that orange glow to some streetlights. Potassium is vital for your nerves to fire; without it, your heart literally wouldn't beat.

Then there’s the high-tech stuff. Cesium is used in atomic clocks. The official definition of a "second" in timekeeping is actually based on the vibrations of a Cesium-133 atom. So, the very first column of the periodic table isn't just about chemistry; it’s how we keep the entire world on schedule.

The Mystery of Francium

Francium is the "ghost" of the group. It’s located at the very bottom of the column. It is so radioactive and unstable that if you actually managed to get enough of it together to see it, the heat from its own radioactivity would probably vaporize it instantly. There is probably less than 30 grams of it in the entire Earth's crust at any given time.

How to Identify Them in the Lab

If you’re ever in a lab and need to figure out which one you’re looking at, you do a flame test. Each one has a "signature" color when you burn it.

- Lithium: A beautiful, deep crimson red.

- Sodium: That bright, unmistakable "school bus" yellow.

- Potassium: A soft, pale lilac or violet.

- Rubidium: A reddish-violet.

- Cesium: Sky blue.

Actionable Steps for Mastering the Periodic Table

If you want to actually remember where the alkali metals are located in the periodic table and how they work, don't just stare at the chart.

- Visualize the "S" Block: Remember that the first two columns (Alkali and Alkaline Earth metals) are the "s" block. Think of them as the foundation of the table on the left.

- The "Rule of One": Associate Group 1 with the number one. One valence electron. One main goal (to lose it). One charge ($+1$) when they become ions.

- Safety First: If you ever handle these in a chemistry setting, remember they are stored in mineral oil. This keeps them away from the oxygen and moisture in the air. Never touch them with bare hands; the moisture on your skin is enough to cause a burn.

- Check the Exceptions: Always double-check if your source includes Hydrogen. If a quiz asks "Which element in Group 1 is not a metal?", you now know the answer is Hydrogen.

The periodic table is a map of how the universe is built. By knowing that the far-left column houses the most reactive, electron-sharing metals in existence, you’ve already mastered one of the most important "neighborhoods" in science.