It started with a low hum. Then, a roar. On September 7, 1940, the sky over London didn’t just turn dark because the sun went down; it turned black because nearly 350 German bombers, escorted by over 600 fighters, swarmed the city. People stood on the streets of Stepney and Silvertown, heads craned back, genuinely confused. They hadn't heard the sirens yet. By the time the first sticks of bombs hit the Royal Victoria Dock, the question of when was the London Blitz wasn't a historical inquiry—it was a terrifying, immediate reality.

For 57 consecutive nights, London burned. Think about that for a second. Every single night for almost two months, the Luftwaffe dropped high explosives and incendiaries on a civilian population. It didn't stop until May 1941. While we often think of the Blitz as one singular, blurry event of the 1940s, it actually followed a very specific, brutal calendar that shifted from the docks to the West End, and eventually to the entire UK.

The Start Date: Black Saturday and the First Wave

If you’re looking for the exact moment it all kicked off, mark your calendar for September 7, 1940. History buffs call it "Black Saturday." Before this, Hitler’s air force, the Luftwaffe, had been mostly busy trying to knock out the Royal Air Force (RAF) airfields. They were losing that fight, honestly. So, they changed tactics. They went for the heart of the British Empire to break the people’s will.

The first attack hit the East End. Why? Because that’s where the industry was. The Thames was lined with warehouses full of sugar, grain, and timber—basically a giant tinderbox. By 6:00 PM that evening, the fires were so massive that incoming German pilots didn't even need their navigators. They just flew toward the glowing red horizon.

The 57-Night Streak

From that Saturday until November 2, London was bombed every single night. Rain or shine. It sounds like a movie trope, but it’s documented fact. People got into this weird, exhausted rhythm. They’d finish work, grab a blanket, and head for the "Tube" (the London Underground). Interestingly, the government actually tried to ban people from using the subway stations as shelters at first. They thought it would create a "deep shelter mentality" and make people too scared to come out.

People ignored them. They bought tickets for the trains just to get onto the platforms and stayed there. Eventually, the authorities gave up and installed bunk beds.

📖 Related: London to Canterbury Train: What Most People Get Wrong About the Trip

Why the Timing of the Blitz Matters

Understanding when was the London Blitz isn't just about memorizing dates for a quiz. The timing explains the evolution of urban warfare. By late 1940, the Germans realized that bombing the docks wasn't enough to make Churchill surrender. So, they expanded.

In October, the "Moonlight Sonata" raids began. These were timed specifically around the full moon to give pilots better visibility. On October 14, a massive bomb hit the road outside Balham Station. It breached the water mains and gas pipes. People who had sought safety in the station were trapped in a horrific mix of rising water and escaping gas. It was a mess. It showed that nowhere—not even deep underground—was 100% safe.

The Mid-Point: Shifting Targets and the Coventry Outlier

By mid-November 1940, the Luftwaffe realized London was big. Really big. Too big to destroy quickly. So, they started hitting other cities like Birmingham, Bristol, and most famously, Coventry on November 14.

But London never really got a break. The raids became less frequent but more intense. The "Second Great Fire of London" happened on the night of December 29, 1940. This is the night of that famous photo—St. Paul’s Cathedral standing tall while everything around it is a wall of smoke. The Germans timed this raid for a low tide on the Thames, meaning the fire brigade couldn't pump enough water from the river to fight the flames. It was calculated. It was cold.

- September 1940: Focus on docks and the East End.

- October 1940: Shift to nighttime "nuisance" raids and city-wide disruption.

- December 1940: Massive incendiary attacks designed to burn the city to the ground.

- January to March 1941: Heavier bombs (the "Satan" bombs) used to maximize structural damage.

The Final Blow: May 1941

So, when did it actually end? The "official" end of the Blitz is usually cited as May 11, 1941. The night before, May 10, was arguably the worst night of the entire war for London.

👉 See also: Things to do in Hanover PA: Why This Snack Capital is More Than Just Pretzels

More than 500 German bombers dropped over 700 tons of explosives. The House of Commons was hit and destroyed. The British Museum took a direct hit. Over 1,400 people died in just those few hours. But then, almost as quickly as it started, the heavy bombing stopped. Hitler was moving his planes east. He was getting ready to invade the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa). He needed those bombers elsewhere.

Londoners woke up on May 12, waited for the sirens that night, and... nothing. It was quiet. Well, "quiet" is relative—the city was a ruin—but the constant rain of fire had paused.

Common Misconceptions About the Blitz Timeline

Most people think the Blitz was the only time London was bombed. Not true. You’ve got the "Little Blitz" in early 1944 (Operation Steinbock), which was a last-gasp effort by the Luftwaffe. Then you had the V-1 "Doodlebugs" and the V-2 rockets starting in June 1944. Those were terrifying because you couldn't hear the V-2 coming. It was supersonic. You’d just be walking down the street and—boom—the block was gone.

But the "Blitz" specifically refers to that 1940–1941 window. It’s also a myth that everyone was "keep calm and carry on" all the time. Real diaries from the time, like those documented by Mass-Observation, show that people were exhausted, irritable, and sometimes downright terrified. Crime actually went up. Looting happened in bombed-out houses. It was a very human, very messy period of time.

Visiting Blitz Sites Today

If you're in London and want to see the physical legacy of when was the London Blitz, you don't have to look far. The scars are everywhere if you know the "tell."

✨ Don't miss: Hotels Near University of Texas Arlington: What Most People Get Wrong

Look at the brickwork on old housing blocks. If you see a row of Victorian terraces and then suddenly a 1950s concrete building in the middle, that’s almost certainly a bomb site.

- St. Dunstan in the East: This is a church that was partially destroyed in 1941. Instead of rebuilding it, they turned it into a public park. It’s hauntingly beautiful and sits right in the middle of the City’s financial district.

- The Imperial War Museum: They have a dedicated "Blitz Experience" that uses sounds and smells to replicate what it felt like in a shelter.

- The Firefighters' Memorial: Located near St. Paul’s, it commemorates the men and women who fought those 1940 fires.

- Bethnal Green Tube Station: Visit the "Stairway to Heaven" memorial outside the station. It commemorates the 173 people who died in a crush during an air raid siren in 1943. While not during the primary Blitz window, it's a vital part of the home-front story.

Practical Takeaways for History Enthusiasts

To truly grasp the timeline, you need to look past the "Keep Calm" posters and dive into the logistics. The Blitz lasted roughly 8 months. It claimed over 40,000 civilian lives across the UK, half of them in London.

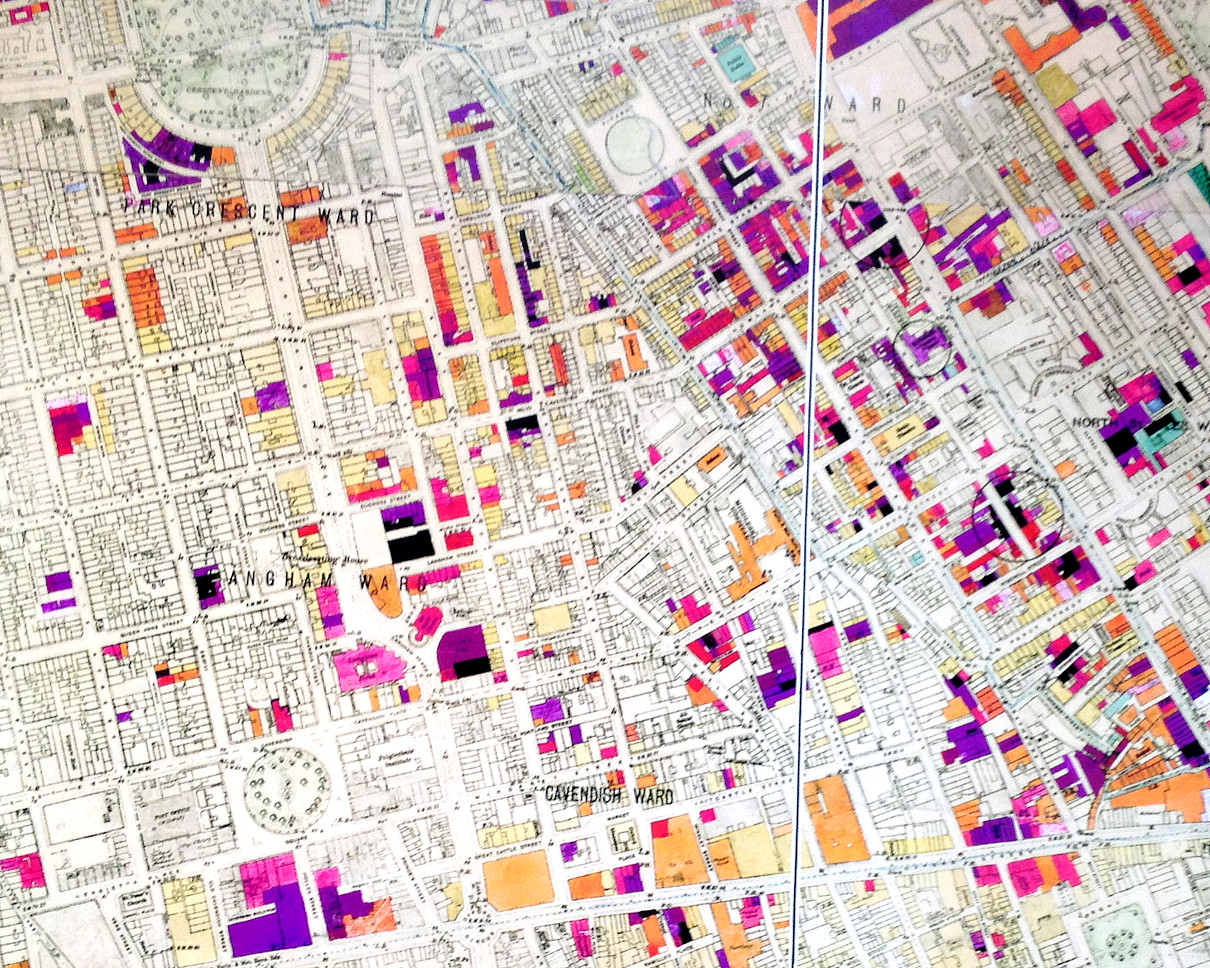

If you're researching family history or just curious about a specific street, the London Bomb Map (Bomb Sight project) is an incredible resource. It uses the digitised records of the Bomb Census to show exactly where every bomb fell between October 1940 and June 1941. You can zoom in on a specific house. It’s a sobering way to see how concentrated the destruction was.

To get a real feel for the atmosphere, read The Heat of the Day by Elizabeth Bowen or The Ministry of Fear by Graham Greene. They were written by people who lived through it and captured the weird, hallucinogenic feeling of a city that only lived at night.

Next time you're walking through London and see a weirdly modern gap in a historic street, check the date of the building. You're likely looking at the spot where the timeline of the Blitz intersected with someone’s living room seventy-five years ago.