Ask most people when was the industrial revolution, and they’ll probably reflexively mutter something about the mid-1700s. They aren't wrong. But they aren't exactly right, either. History isn't a light switch. You don't just wake up one Tuesday in 1760 and realize you've swapped your hand-plow for a steam engine.

It was messy. It was slow.

Actually, the "when" of it all is a bit of a moving target depending on who you ask. Most historians, like the late Eric Hobsbawm, tend to argue that it "broke out" in the 1780s. But if you're looking at the technological seeds, you have to go back way further, into the soggy coal mines of the late 1600s. It's a massive, sprawling transition that fundamentally reshaped how humans exist on this planet. We went from living by the sun to living by the clock.

The First Wave: 1760 to 1840

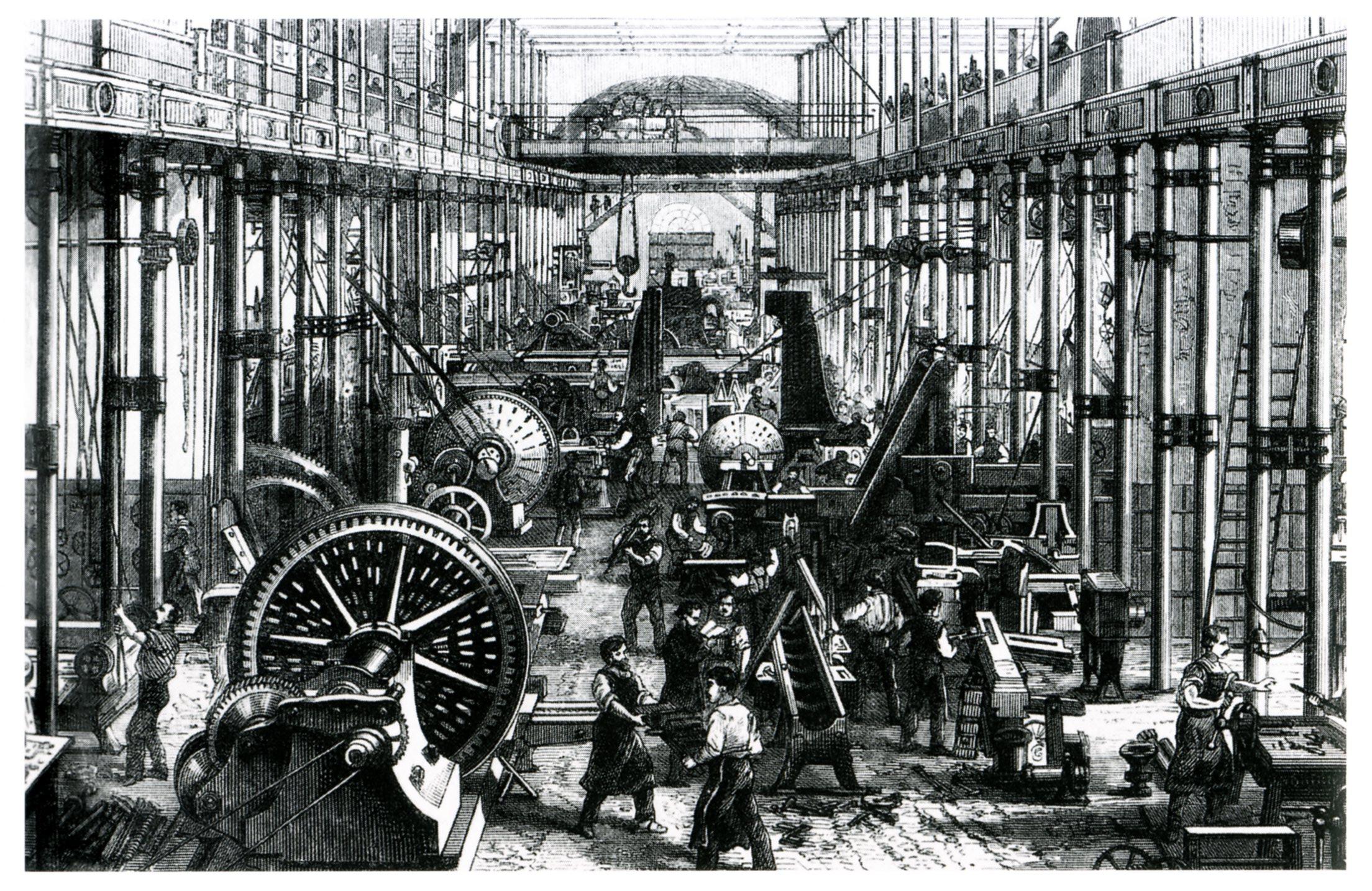

The "First" Industrial Revolution is the one you see in the movies. Chimneys. Smog. Dickensian orphans. It basically kicked off in Great Britain around 1760. Why then? A mix of stable politics, colonial wealth, and a lot of very accessible coal.

James Watt gets all the credit for the steam engine, but honestly, Thomas Newcomen had a clunky version working back in 1712. Watt just made it so it didn't suck. By the 1770s, Watt’s engine was actually efficient enough to be used in factories, not just for pumping water out of mines. This shifted the "when" from a slow crawl to a sprint.

Textiles led the charge. Before this, making a shirt was a nightmare of manual labor. Then came the Flying Shuttle and the Spinning Jenny. Suddenly, you had a "factory system." People stopped working at home and started commuting. That’s a huge psychological shift. Imagine being a weaver in 1750 who works when they feel like it, and by 1790, you’re being screamed at by a foreman because you’re two minutes late to a 14-hour shift.

Why the British?

It wasn't just about being smart. The Dutch were arguably more "advanced" in some ways, but they lacked the specific combination of cheap coal and expensive labor. In Britain, people were pricey. Machines were a way to cut costs. In places like India or China at the time, labor was so cheap that there was no real financial incentive to build a massive, expensive machine to do what fifty people could do for pennies.

The Second Wave: 1870 to 1914

If the first revolution was about steam and iron, the second was about steel, chemicals, and electricity. This is often called the Technological Revolution. It’s a completely different beast.

By 1870, the world was already "industrialized" in patches, but this second burst turned it into a global phenomenon. This is when the United States and Germany really started to flex. You get the Bessemer process, which made steel cheap and ubiquitous. Before this, steel was a luxury. Afterward? It’s the skeleton of every skyscraper in New York.

Then there’s the oil.

John D. Rockefeller didn't just get rich by accident; he arrived exactly when the world needed a way to light its lamps and, eventually, fuel its internal combustion engines. This period ended abruptly with the start of World War I in 1914. It’s kind of tragic. All that incredible innovation in chemistry and engineering was immediately pivoted toward creating more efficient ways to kill people on a mass scale.

The "Long" Industrial Revolution

Some historians, like Jan de Vries, argue for something called the "Industrious Revolution." This theory suggests that people started working harder and longer before the machines arrived. They wanted stuff. They wanted tea, sugar, and tobacco. To get those things, they had to produce more goods to sell.

✨ Don't miss: The Truth About Buying a 2 Person Electric Scooter Without Getting Scammed

So, if you’re asking when was the industrial revolution because you want to know when the human mindset changed, you might be looking at the late 1600s.

It’s also worth noting that it didn't happen everywhere at once. While Britain was building railroads in the 1830s, most of the world was still farming exactly how their ancestors did in the Middle Ages. Russia didn't really get its act together until the very end of the 19th century. Japan pulled off a miraculous "speedrun" of industrialization during the Meiji Restoration starting in 1868, doing in 40 years what took Europe 150.

Major Milestones and Their Timings

- 1712: Newcomen’s atmospheric engine (the prototype).

- 1764: The Spinning Jenny (making yarn fast).

- 1769: James Watt patents the improved steam engine.

- 1807: Robert Fulton’s steamboat makes its first trip.

- 1830: The Liverpool and Manchester Railway opens (the birth of the rail age).

- 1856: The Bessemer Process (cheap steel).

- 1879: Edison’s light bulb (the end of the dark).

- 1903: Wright Brothers fly (the world gets smaller).

- 1908: Ford’s Model T (mass production perfected).

The Dark Side of the Timeline

We can't talk about the timing without talking about the cost. The "when" of the Industrial Revolution is also the "when" of massive environmental degradation and systemic exploitation.

Child labor wasn't a glitch; it was a feature of the early timeline. In the 1830s, about a third of the workers in British cotton mills were children. The legal pushback didn't really gain teeth until the Factory Act of 1833, and even then, it was slow going.

And then there's the carbon.

Scientists generally point to the mid-18th century as the baseline for when we started pumping CO2 into the atmosphere at unnatural rates. If you look at an ice core sample, the spike begins right around 1750-1760. Our modern climate crisis is literally a legacy of the timing of the Industrial Revolution. It’s the bill that’s finally coming due.

Was there a Third or Fourth?

You’ll hear economists talk about the Third Industrial Revolution (the Digital Revolution) starting in the 1950s with computers. And now, the "Fourth Industrial Revolution" (Industry 4.0), involving AI and gene editing.

It’s all a bit of a marketing term, honestly.

But it helps to see industrialization not as a finished event in a history book, but as a continuous process of acceleration. We are still in it. The "when" is "now."

Summary of Practical Takeaways

Understanding the timeline helps make sense of the modern world. If you're looking for actionable insights from this history, consider these:

- Technology isn't enough: The steam engine existed for decades before it changed the world. It required the right economic conditions (expensive labor, cheap fuel) to actually take off.

- Infrastructure is the multiplier: The First Revolution was limited until the railroads of the 1830s connected everything. Innovation without distribution stays local.

- Social lag is real: Technology always moves faster than the law. We saw it with 19th-century child labor, and we see it now with data privacy and AI.

- Energy transitions take time: We didn't move from wood to coal overnight. It took 100 years. Our current shift from fossil fuels to renewables is following a similar, frustratingly slow trajectory.

If you're researching this for a project or just out of curiosity, stop looking for a single date. Look for the overlaps. Look at how a boring improvement in a water pump in 1712 led to you being able to order a pizza on a smartphone in 2026. Everything is connected.

To dig deeper into the specific data of this era, you should look into the "Maddison Project Database," which tracks historical GDP and population shifts. It’s the gold standard for seeing exactly how the needle moved during the 18th and 19th centuries. For a more narrative approach, "The Lever of Riches" by Joel Mokyr is probably the best deep dive on why the timing worked out the way it did.