Ask a historian when the British Industrial Revolution happened, and you'll likely get a heavy sigh.

Most textbooks give you a neat, tidy window. They usually point to 1760 through 1840. But history is rarely that polite. If you were a weaver in Lancashire in 1750, or a coal miner in Durham in 1860, your "revolution" didn't start or stop because a textbook said so. It was a messy, loud, and often painful transition that stretched across generations.

The truth is, pinpointing exactly when was the British Industrial Revolution depends entirely on what you’re looking at. Is it the technology? The social shifts? The economic data? Honestly, it’s all of the above, but the timeline is way more elastic than you think.

The 1760 Starting Gun: Why We Pick This Date

The 1760 date isn't just a random number someone plucked out of the air. It’s tied to the accession of King George III, but more importantly, it marks the moment when several disconnected inventions started to "click" together.

🔗 Read more: Is This Is a Call Foo Still a Real Thing? What Most People Get Wrong

Before 1760, Britain was already changing. We call this the "proto-industrial" phase. People were making things in their cottages—the "putting-out system"—but it was slow. Then came the big hitters. You’ve got James Watt tinkering with Newcomen’s clunky steam engine. You’ve got James Hargreaves coming up with the Spinning Jenny.

These weren't just "cool gadgets." They were the first signs of a fundamental shift in how humans interacted with the world.

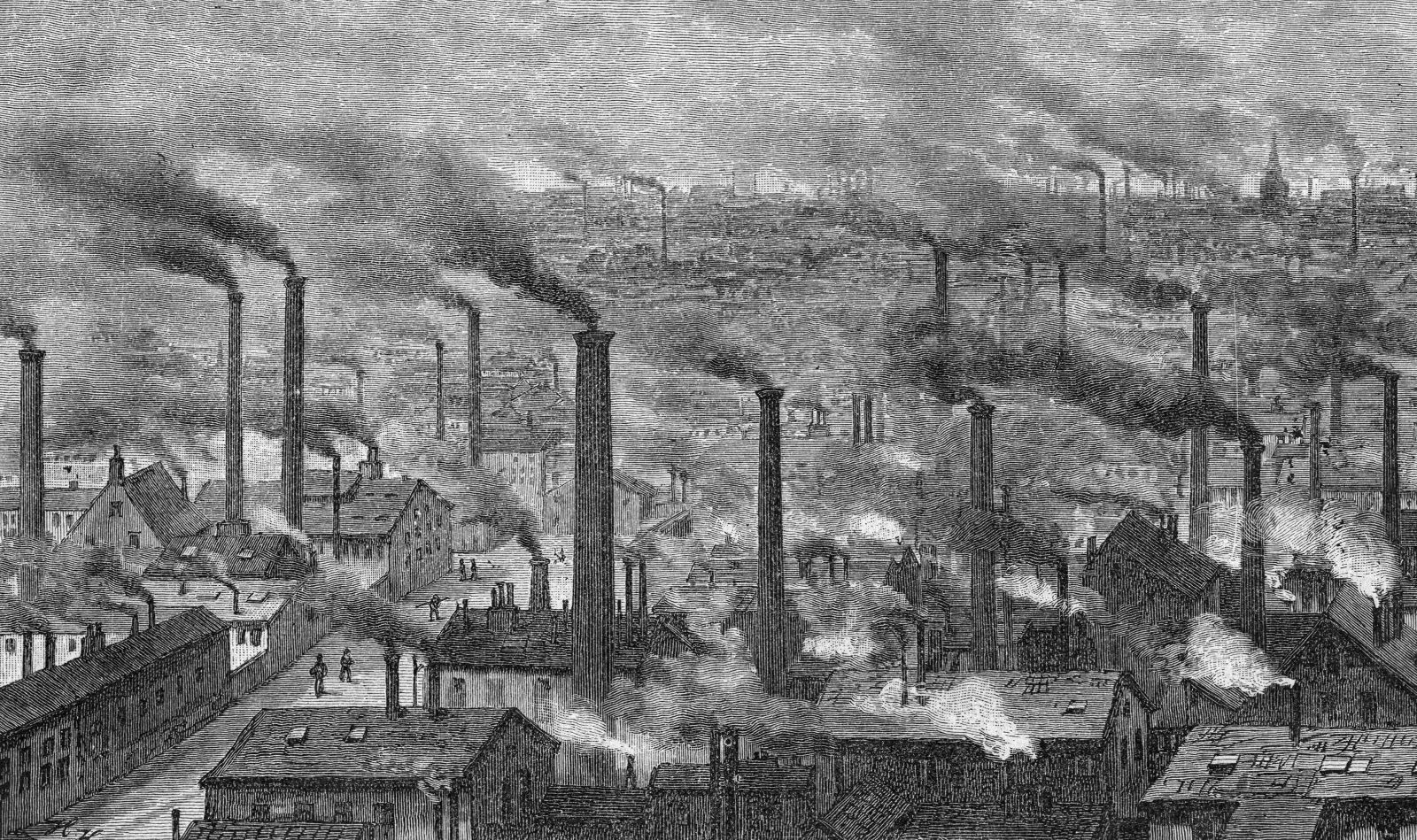

Think about it. For thousands of years, if you wanted to move something or make something, you used muscles—human or animal—or maybe a bit of wind and water. Suddenly, we were burning rocks to create motion. That's a massive leap. Historian T.S. Ashton, who wrote the definitive (though now slightly debated) text The Industrial Revolution, famously argued that the "revolution" was a wave of gadgets that broke over England. He wasn't wrong, but the "when" of it started long before the smoke cleared.

The Mid-Point Surge and the Great Exhibition

By the 1820s, the revolution was in its "awkward teenage years." It was growing fast, it was volatile, and it was changing the landscape literally and figuratively. This is when the "when" becomes undeniable.

The 1830s saw the railway mania. Before this, "fast" meant a horse. After this, the world shrank. If you're looking for the peak of the British Industrial Revolution, many look at 1851. That was the year of the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in London.

Britain was essentially bragging.

The country showed off its steam hammers, its high-pressure engines, and its massive looms. At that specific moment, Britain produced about half of the world's iron and coal. It was the "workshop of the world." If you had to put a pin in a map of time and say, "This is it, this is the height," 1851 is your best bet.

But here’s where it gets tricky.

While the "first" Industrial Revolution—the one based on textiles, coal, and iron—was peaking, the "second" one was already simmering. This later phase moved into chemicals, electricity, and steel. So, did the revolution end in 1840? Not really. It just evolved.

The Arnold Toynbee Effect: Why We Call It a Revolution

We actually owe the term "Industrial Revolution" to a guy named Arnold Toynbee. No, not the historian from the 1900s, but his uncle, who gave a series of lectures in 1881.

Toynbee was the one who popularized the idea that this period was a sudden, violent break from the past. He saw the misery in the slums and the massive wealth of the factory owners and thought, "This is a revolution."

However, modern "cliometricians"—historians who use hardcore data and math—sorta disagree.

The Great Divergence Debate

Economic historians like Nicholas Crafts have looked at the GDP growth during the 1700s and 1800s. Their findings were a bit of a shock. They found that growth was actually quite slow. It wasn't a sudden explosion; it was more like a slow, steady burn.

- 1700-1760: Growth was about 0.7% per year.

- 1780-1830: It crept up to about 1.3%.

That doesn't sound like a "revolution," does it? It sounds like a slow grind. This has led many experts to argue that the British Industrial Revolution wasn't an event, but a process that started as early as the 1600s with the expansion of trade and the Scientific Revolution.

Regional Timelines: Not Everywhere Changed at Once

When we ask when was the British Industrial Revolution, we often talk about Britain as a single unit. It wasn't.

Manchester was the "Shock City." It transformed almost overnight. But if you went to the South of England, to places like Dorset or Somerset, life in 1840 looked remarkably similar to life in 1740. They were still farming. They were still tied to the seasons.

Scotland had its own timeline. The "Scottish Enlightenment" fueled a massive industrial boom in Glasgow and the Clyde Valley, but it started slightly later and focused heavily on heavy engineering and shipbuilding. Wales became the coal mining powerhouse, but its peak came much later in the 19th century.

It’s better to think of it as a series of fires starting in different parts of a forest. Some caught early and burned bright; others took decades to ignite.

The Human Cost: A Different Way to Measure Time

If you measure the revolution by human height and health, the timeline looks even grimmer.

Interestingly, as the British economy grew, the physical well-being of the working class actually declined for a while. This is known as the "Antebellum Puzzle" (though that's usually a US term, it applies here too). Between 1780 and 1850, the average height of British workers actually dropped.

Why? Because city life was toxic.

Cholera, typhus, and poor nutrition took their toll. So, if you're asking when the revolution happened for the average person, the answer is: it happened when their lives were turned upside down, often for the worse, before the "Standard of Living" finally started to climb in the late 1800s.

The "When" for a child factory worker in 1810 was a 14-hour workday. The "When" for a wealthy merchant in 1850 was a mansion in the suburbs and a railway ticket to the coast.

Was it over by 1900?

Technically, by the time Queen Victoria died in 1901, the "British" part of the Industrial Revolution was yesterday's news. The United States and Germany had already started to overtake Britain in steel and chemical production.

But the infrastructure stayed. The canals, the rail lines, the soot-stained brick factories—they defined Britain for the next century.

In some ways, the British Industrial Revolution didn't "end" until the deindustrialization of the 1970s and 80s. That’s when the last of the great coal mines and steel mills—the direct descendants of those 18th-century inventions—started to close their doors.

Mapping the Real Timeline

If you really want to understand the flow, don't look for a single date. Look for these phases:

- The Preparation (1660-1760): The rise of the merchant class, the Bank of England, and early coal mining.

- The Take-off (1760-1790): Water frames, spinning jennies, and Watt's steam engine.

- The Consolidation (1790-1830): The Napoleonic Wars actually pushed innovation in iron production and standardizing parts.

- The Railway Age (1830-1850): The total annihilation of distance.

- The High Victorian Era (1850-1870): Peak dominance and the shift toward global finance.

The Verdict on the "When"

So, when was the British Industrial Revolution?

If you're taking a history test: 1760 to 1840.

If you're looking at the data: 1780 to 1850.

If you're looking at the world it created: It hasn't ended yet.

We are still living in the tail end of the carbon-based economy that those early engineers built. Every time you flip a switch or get on a plane, you're using a descendant of a machine built in a drafty British workshop three centuries ago.

To truly grasp this period, you should look beyond the dates. Look at the shift in mindset. It was the moment humanity stopped being a passenger on the planet and started trying to drive the bus.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you want to dive deeper into this era beyond just the dates, here is how you can actually "see" the revolution today:

- Visit the Iron Bridge: Go to Shropshire. The bridge built in 1779 is still there. It’s the first major structure in the world made of cast iron. Standing on it is the closest you’ll get to a time machine.

- Read the Primary Sources: Skip the textbooks for a second. Look at the Report from the Select Committee on the Bill for the Regulation of the Factories (1832). It’s heartbreaking, but it’s the real, unvarnished history of the "When."

- Track Your Own Ancestry: Use sites like Ancestry or FamilySearch. If you have British roots, you can literally watch your family move from "Agricultural Laborer" in 1790 to "Cotton Spinner" in 1820. That is the revolution in a nutshell.

- Explore the Geography: Look at a map of England's "Black Country." See how the towns are clustered around coal seams. The geography dictated the "when" as much as the inventors did.

Understanding the timing of this era isn't about memorizing a year. It's about recognizing a massive, tectonic shift in the human story—one that started with a few curious people in the English Midlands and ended up changing every single life on Earth.