History is messy. If you ask a quick search engine when was the 14th amendment passed, you might get a single date like July 9, 1868. But that's just the day it was ratified. Honestly, the "passing" of this amendment was a multi-year political brawl that almost tore the country apart—again—just as the smoke was clearing from the Civil War.

It wasn't a simple vote. It was a transformation.

The 14th Amendment is basically the most important part of the Constitution that most people can't recite. It’s the "Equal Protection" one. It’s the "Due Process" one. It’s the reason why, legally speaking, the United States became a modern democracy instead of a loose collection of states with their own rules on who counts as a person.

The Long Road to 1866

To understand when this actually happened, we have to look at the winter of 1865. The war was over. Lincoln was gone. Andrew Johnson, a guy who was—to put it mildly—not a fan of civil rights for formerly enslaved people, was in the White House. Southern states were already passing "Black Codes." These were basically slavery by another name, keeping people in a state of permanent servitude.

✨ Don't miss: The Presidency of John Adams: Why Everyone Remembers the Mistakes and Misses the Genius

Congress had enough.

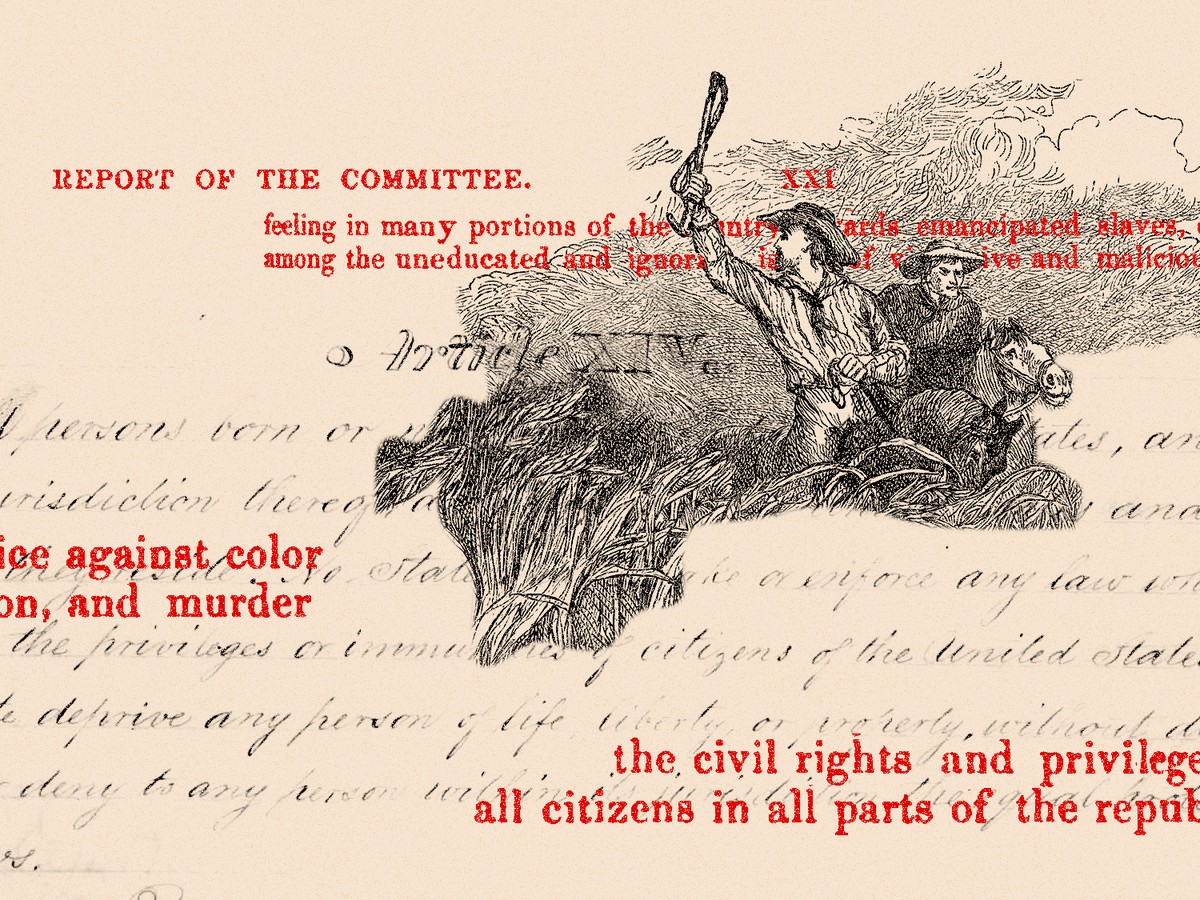

In early 1866, the Joint Committee on Reconstruction started drafting what would become the 14th Amendment. They didn't just want a law; they wanted something permanent. Laws can be repealed. Amendments stay.

The House of Representatives actually passed the resolution on May 10, 1866. The Senate followed on June 8. It was a tense summer in D.C. If you were walking the streets back then, the air was thick with the realization that the country was being legally rewired. Finally, on June 16, 1866, the amendment was officially proposed to the states.

The Ratification War (1866-1868)

Passing it in Congress was the easy part. Ratification was a nightmare.

You need three-fourths of the states to agree. In 1866, that was a tall order because the Southern states flat-out refused. Tennessee was the outlier; they ratified it pretty quickly in July 1866 and got readmitted to the Union. But the rest of the former Confederacy? They said no.

This created a massive constitutional crisis.

🔗 Read more: Major Events in the 90s That Actually Changed the Way We Live

Congress responded with the Reconstruction Acts of 1867. This was basically a "pay to play" system. If a Southern state wanted to have representatives in Congress again, they had to ratify the 14th Amendment. Critics called it "ratification at the point of a bayonet." Maybe it was. But without it, the amendment would have died right there in the late 1860s.

The Final Count

By 1868, the momentum became unstoppable.

- Florida signed on in June.

- North Carolina and Louisiana followed in early July.

- South Carolina jumped in on July 9, 1868.

That was it. That was the magic number. South Carolina’s vote provided the 28th state needed out of the 37 states then in the Union.

But even then, it wasn't smooth. Ohio and New Jersey actually tried to "withdraw" their ratification. Secretary of State William Seward was in a weird spot. He basically issued a proclamation saying, "Well, if these withdrawals don't count, then it's part of the Constitution." Congress eventually passed a concurrent resolution on July 21, 1868, declaring the 14th Amendment the law of the land, and Seward issued the final certification on July 28.

So, if you're looking for the specific date when was the 14th amendment passed, July 9, 1868, is your winner for ratification, but July 28 is when the paperwork was finally, officially finished.

Why the Timing Matters Today

If the 14th Amendment hadn't passed exactly when it did, the 20th century would have looked unrecognizable. We often think of "The Bill of Rights" protecting us from the states, but originally, it didn't. Before the 14th Amendment, a state could technically censor your speech or take your property without much federal recourse.

Section 1 changed everything:

"All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside."

That single sentence created birthright citizenship. It wiped out the horrific legacy of the Dred Scott decision. It ensured that "Due Process" wasn't just a federal concept, but a state obligation.

Common Misconceptions About 1868

People often think the 14th Amendment gave Black men the right to vote. It didn't. Not exactly. It actually penalized states that denied the vote by reducing their representation in Congress, but it didn't explicitly guarantee the franchise. That didn't happen until the 15th Amendment was ratified in 1870.

💡 You might also like: JD Vance and the Little Miami River: What Really Happened

Another weird quirk? The amendment also dealt with the national debt. It made sure the U.S. would pay its debts from the war but forbade paying any debts incurred by the Confederacy. It also barred former rebels from holding office—a clause that has seen a massive resurgence in legal discussions recently regarding the 14th Amendment's Section 3.

How to Use This Knowledge

Understanding the timeline of the 14th Amendment isn't just for history buffs or trivia nights. It's about knowing the "Second Founding" of America.

If you want to dive deeper into how this affects your life today, start by looking at Incorporation Doctrine. This is the legal process where the Supreme Court uses the 14th Amendment to apply the Bill of Rights to the states. Without the events of 1866-1868, most of the rights you enjoy against local government overreach simply wouldn't exist in federal court.

Next Steps for the Curious:

- Read the Five Sections: Don't just look at Section 1. Read Section 3 (the disqualification clause) and Section 4 (the public debt clause) to see how the framers were trying to prevent another war.

- Research the Slaughter-House Cases (1873): This was the first major Supreme Court test of the amendment. It actually gutted much of the amendment's power for decades, showing that passing an amendment is only half the battle—interpretation is the other half.

- Visit the National Archives Online: You can view high-resolution scans of the original 1866 joint resolution to see the actual handwriting of the men who tried to rebuild a broken nation.