You probably haven't seen one in the wild. Most people haven't. If you walked into a local 7-Eleven today and tried to buy a Slurpee with a bill featuring Alexander Hamilton’s face—wait, no, that’s the ten. For the big one, we’re talking about Grover Cleveland. If you handed a clerk a $1,000 bill, they’d likely think you were playing with movie prop money or running a very high-stakes prank.

But it’s real. Or it was.

When people ask when was the 1000 dollar bill discontinued, they usually expect a single date, like a clean-cut retirement party. History is messier than that. The short answer is 1969, but the engines that stopped the printing presses actually cooled down decades earlier.

Money is weird. We think of it as this permanent, physical thing, but the U.S. Treasury treats denominations like software updates. Some get patched, some get deprecated, and some—like the $1,000 bill—get pulled from the shelf because they make it way too easy for the wrong people to move a lot of wealth in a very small briefcase.

The Slow Fade: 1945 to 1969

Technically, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing stopped physically printing the $1,000 bill in 1945. World War II was wrapping up. The economy was shifting. The government realized they had plenty of these high-value notes circulating between banks, and they didn't really need to crank out new ones.

For twenty-four years, the bills stayed in circulation. They were the ghosts of the financial system. You could go to a bank, ask for one, and if they had it in the vault, it was yours.

Then came July 14, 1969.

✨ Don't miss: Getting a Mortgage on a 300k Home Without Overpaying

That’s the "official" date most historians point to. The Federal Reserve issued a massive recall. It wasn't just the $1,000 bill getting the axe; they also scrapped the $500, the $5,000, and the legendary $10,000 note. The reason? Lack of use. Honestly, that was the public-facing excuse. The real reason was more about crime. By the late 60s, the "War on Drugs" was starting to simmer. Organized crime loved high-denomination bills. Think about it. You can fit $1 million in $1,000 bills into a standard envelope. Trying to do that with $20 bills requires a literal pallet and a forklift. The Treasury decided that making it harder to move large sums of cash was a solid way to trip up money launderers and tax evaders.

The Grover Cleveland Connection

Most people assume Benjamin Franklin is the highest-ranking face on American currency because of the "All about the Benjamins" culture. Nope. While Franklin sits on the $100, Grover Cleveland—the only president to serve two non-consecutive terms—landed the $1,000 spot.

There were earlier versions, too. Back in the late 1800s, you might have found Alexander Hamilton on a $1,000 bill. But the 1928 and 1934 series, which are the ones collectors mostly hunt today, feature Cleveland. He looks stern. He looks like a man who knows he represents a lot of purchasing power.

Why You Can't Find One (Even Though They Are Legal Tender)

Here is a fun fact to pull out at dinner: $1,000 bills are still legal tender.

If you find one in your grandma's attic, it is technically worth $1,000 at any grocery store. But please, for the love of all things holy, do not spend it at a grocery store. Because the Fed stopped issuing them in '69, they began a "destroy on sight" policy for banks.

Whenever a $1,000 bill hits a bank teller’s drawer, the bank isn't allowed to give it back out to the public. They have to send it back to the Federal Reserve to be shredded. This is why they’ve vanished. It’s a slow-motion extinction event.

🔗 Read more: Class A Berkshire Hathaway Stock Price: Why $740,000 Is Only Half the Story

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, there are still about 165,000 of these bills "in the wild." That sounds like a lot until you realize most of them are sitting in private collections, vacuum-sealed in plastic, or forgotten in safety deposit boxes.

What are they actually worth?

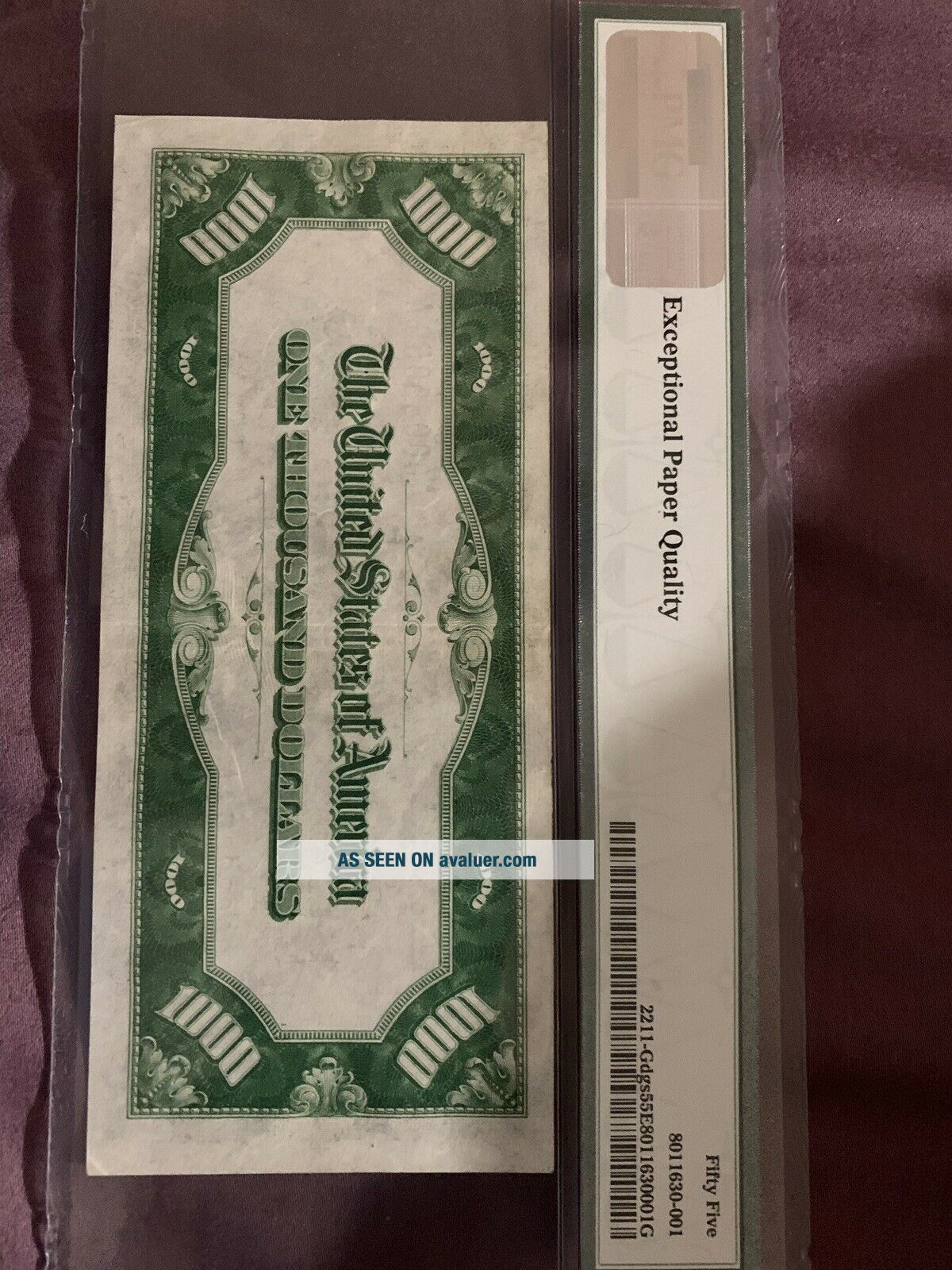

If you tried to sell a 1934 Grover Cleveland note today, you’d be looking at a minimum of $2,000 to $5,000 depending on the condition. If it’s "uncirculated"—meaning it looks like it was printed yesterday—the price rockets.

- Series 1928: These are rarer and often fetch a premium.

- Gold Certificates: Some $1,000 bills were backed by gold. These have bright orange-yellow backs. They are stunning. They are also worth a small fortune to numismatists (coin and paper money collectors).

- Star Notes: If there is a little star next to the serial number, it means it was a replacement bill. Collectors go nuts for these.

The "Secret" $100,000 Bill

While we are talking about high-stakes paper, we have to mention the $100,000 bill.

Most people don't even know it exists. It features Woodrow Wilson. It was never, ever intended for the public. These were "Gold Certificates" used strictly for transactions between Federal Reserve banks. They were printed in 1934 during the height of the Great Depression.

Why? Because back then, moving $100 million between banks involved a lot of paperwork and physical risk. Having a few $100,000 bills made the accounting easier. It is actually illegal for a private citizen to own one of these. If you have one, you’re either a museum curator or you’re about to have a very awkward conversation with the Secret Service.

Is the $1,000 Bill Coming Back?

Probably not.

💡 You might also like: Getting a music business degree online: What most people get wrong about the industry

In fact, there is more pressure to get rid of the $100 bill than there is to bring back the $1,000. Economists like Kenneth Rogoff have argued for years that we should move toward a "less cash" society. The logic remains the same as it was in 1969: big bills help bad guys.

Digital banking and cryptocurrency have basically replaced the need for high-value physical notes. If you need to move $50,000, you use a wire transfer or a digital ledger. You don't stuff your socks with Clevelands.

Plus, there’s the inflation argument. In 1945, $1,000 was equivalent to about **$16,000 today**. It was a massive amount of money. If we printed a bill today that had the same "weight" as the $1,000 bill did back then, it would have to be a $15,000 bill.

The Rarity Factor

What’s fascinating is how these bills have become a sort of "alternative asset." While the stock market zigzags, the value of discontinued currency tends to just... go up. It’s a finite supply. They aren't making any more. Every time one gets accidentally laundered in a pair of jeans or destroyed in a house fire, the remaining ones become more valuable.

Practical Steps if You Actually Find One

Let’s say you’re cleaning out a deceased relative’s belongings and a crisp $1,000 bill falls out of an old book. Do not go to the bank. I repeat: Stay away from the bank. 1. Don't Clean It. This is the biggest mistake beginners make. They think "Oh, this looks dirty, I'll use some soap." Stop. You will destroy the value. Collectors want the original patina, even the dirt.

2. Get a Sleeve. Go to a hobby shop and buy a PVC-free plastic currency sleeve. Protect it from the oils on your skin.

3. Check the "Seal." Is it a green seal? Blue? Red? Gold? The color of the Treasury seal tells you what kind of note it is (Federal Reserve Note, Silver Certificate, Gold Certificate). This drastically changes the price.

4. Find a Reputable Dealer. Look for someone affiliated with the Professional Currency Guilders Association (PCGS) or Paper Money Guaranty (PMG). These are the "gold standards" for grading paper money.

5. Auction vs. Direct Sale. If the bill is in rough shape, a direct sale to a dealer is fine. If it’s a high-grade "gem" note, you might want to send it to an auction house like Heritage Auctions.

The $1,000 bill is a relic of a time when the U.S. government was still figuring out how to balance convenience with security. It’s a piece of art, a piece of history, and a reminder of an era when you could carry a fortune in your vest pocket.

Even though it was discontinued in 1969, its legend has only grown. It represents a sort of "Forbidden Americana"—money that is still money, but isn't. If you ever hold one, take a second to appreciate the weight of it. It’s the closest thing to a financial unicorn we’ve got.

Check the serial numbers on your old family scrapbooks. You might be surprised at what's been hiding in the pages for the last sixty years. Collectors are currently paying top dollar for "fancy" serial numbers (like 00000001 or ladders like 12345678), which can turn a $2,000 bill into a $20,000 payday.