You're sitting there, maybe 30 weeks along, feeling a rhythmic thumping against your ribs and wondering if that’s a foot or a head. It’s a bit of a mind game. Most parents-to-be spend the third trimester obsessing over their baby’s orientation because, let’s be honest, the "breech" word carries a lot of weight in birth plans. So, when do babies turn head down, and more importantly, what happens if they just... don't?

The short answer is that most babies make the big flip by the 36-week mark. But biology isn't a Swiss watch. Some babies are overachievers and settle into the cephalic (head-down) position by 28 weeks, while others are the ultimate procrastinators, flipping literally hours before labor begins. It’s a tight squeeze in there. As the baby grows, the amniotic fluid ratio drops, and the uterus becomes a very cramped studio apartment where turning around becomes a major logistical feat.

The Timeline of the Big Flip

Typically, your healthcare provider will start checking the baby’s position manually—using what are called Leopold’s Maneuvers—around the 32-week mark. Before this, babies are basically Olympic gymnasts. They have plenty of room to do somersaults, and their position on Tuesday might be completely different by Thursday.

By 34 to 36 weeks, the statistics start to lean heavily toward a downward trend. According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), only about 3% to 4% of babies remain in a breech position at full term. That means the vast majority of "flipping" happens in that crucial window between months seven and nine. If you’re at 32 weeks and the head is still up by your heart, don't panic. There is still a massive amount of "room" relatively speaking for that rotation to occur naturally.

Why head down matters

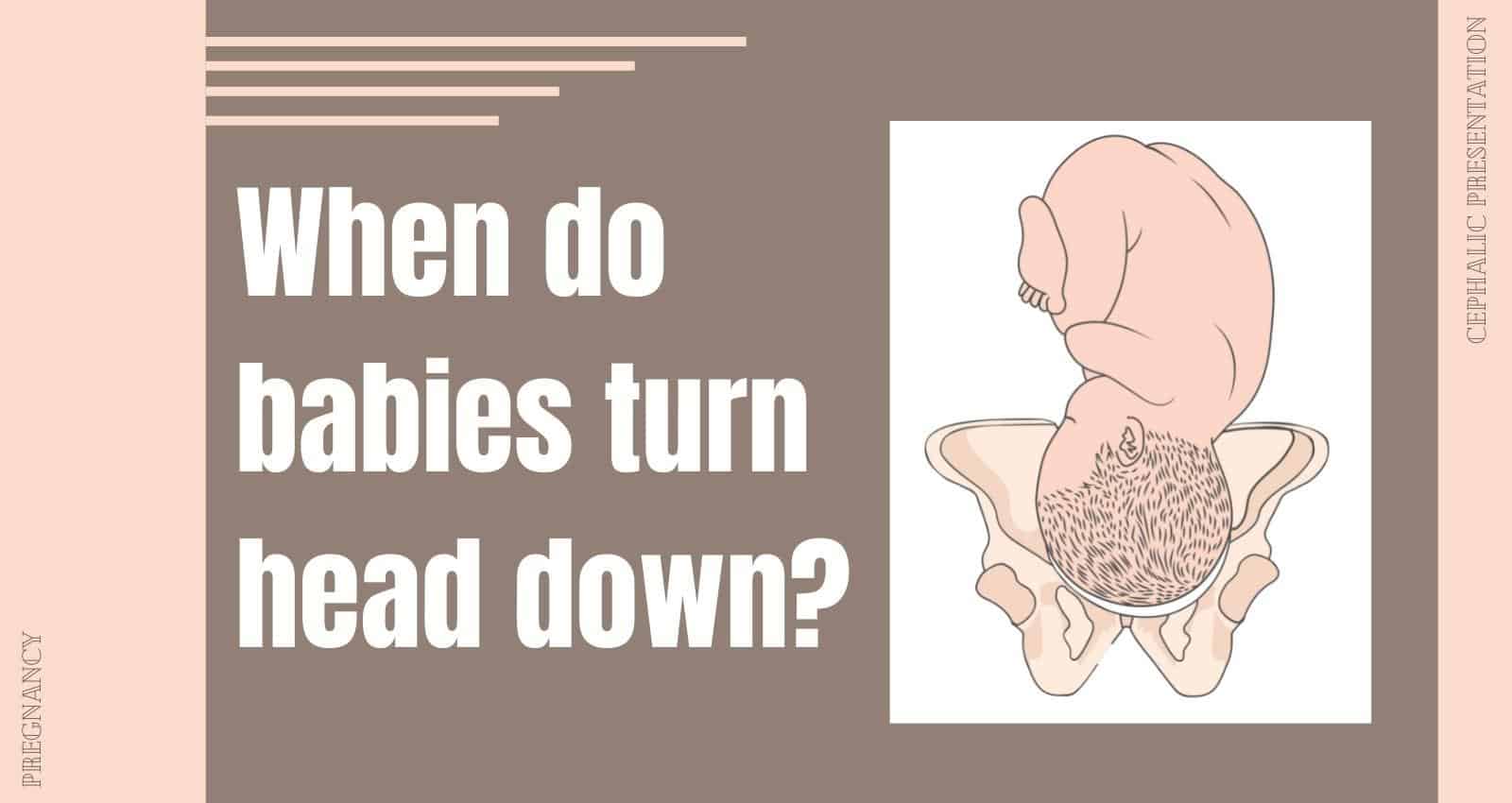

It isn't just about making delivery easier; it's about the mechanics of the pelvis. The baby's head is the largest and hardest part of their body. When the head leads the way, it acts like a natural dilator, applying even pressure to the cervix to help it open. It also fits most snugly into the curve of the pelvic bones. When a baby is breech—buttocks or feet first—the delivery becomes significantly more complex because the largest part of the baby comes out last, increasing the risk of the head getting stuck or the umbilical cord becoming compressed.

Factors That Keep a Baby From Turning

Sometimes, there's a physical reason why a baby stays upright. It isn't usually something the parent did or didn't do. For example, if the placenta is located low in the uterus (placenta previa), it might literally be blocking the baby's "parking spot" at the bottom.

Uterine fibroids can also act like internal speed bumps. If a fibroid is large enough or positioned awkwardly, the baby simply might not have the clearance to make the turn. Then there’s the "cord" factor. Sometimes the umbilical cord is a bit short, or it's looped in a way that creates tension when the baby tries to flip, essentially tethering them in place.

- Amniotic Fluid Levels: Too much fluid (polyhydramnios) means the baby might keep flipping back and forth because they have too much "swimming" room. Too little fluid (oligohydramnios) means they are "shrink-wrapped" and can't move easily.

- The Shape of Your Pelvis: Every body is built differently. Some pelvic shapes are more accommodating to a head-down baby than others.

- Multiple Pregnancies: If you're carrying twins, the sheer lack of real estate often results in at least one baby staying breech or transverse (sideways).

What Does it Feel Like When They Turn?

Honestly, it’s rarely subtle. Many people describe the sensation of the baby turning as a "rolling" or "shifting" feeling that can be quite intense, sometimes even a bit nauseating for a second. You might feel a sudden, sharp pressure in your bladder—the classic "lightning crotch"—as the heavy head settles onto your pelvic floor.

Once they are head down, the kicks will change. Instead of feeling those sharp jolts down low near your cervix or rectum, you’ll start getting "rib kicks." If you feel a hard, round mass right under your ribs, that’s likely the baby’s butt. If you feel small, fluttery movements low down, those are the hands.

When the Baby Stays Breech: The 37-Week Turning Point

If you hit 37 weeks and your little one is still stubborn, your doctor or midwife will likely bring up an ECV, or External Cephalic Version. This is a procedure where a doctor literally tries to roll the baby from the outside of your stomach.

It sounds intense. It kind of is.

Success rates for ECV hover around 58%, according to a study published in the British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. It’s usually done in a hospital setting so they can monitor the baby's heart rate, and sometimes they give you a medication to relax your uterus. It’s not a guarantee, but for many who are hoping for a vaginal birth, it’s a viable "last-ditch" effort before discussing a scheduled C-section.

Natural methods and "The Spinning Babies" approach

Many parents swear by the "Spinning Babies" techniques, which involve specific stretches and inversions to create more space in the pelvis. While clinical evidence on these is mixed, they are generally considered safe as long as you aren't doing anything extreme. The idea is to relax the ligaments supporting the uterus (the round ligaments and uterosacral ligaments) so the baby has the best possible path to turn on their own.

Moxibustion is another one people talk about. It’s a traditional Chinese medicine technique involving burning mugwort near a specific pressure point on the pinky toe. Sounds wild, right? But some studies, including research cited by the Cochrane Library, suggest it might actually help encourage breech babies to turn by increasing fetal activity.

Practical Steps for the Final Weeks

Don't spend your whole third trimester upside down on a couch cushion. Instead, focus on "optimal fetal positioning" by being mindful of how you sit. If you spend eight hours a day slumped back in a recliner or a bucket seat at a desk, your pelvis is tucked under, which can encourage the baby to settle into a "sunny-side-up" (posterior) or breech position.

💡 You might also like: My Dog Ate My Birth Control: Why You Probably Don't Need to Panic

Try sitting on an exercise ball. This keeps your knees lower than your hips and encourages your pelvis to open up. Lean forward when you’re watching TV. Spend a few minutes each day on all fours (the hands-and-knees position). Gravity is your friend here; it helps the heaviest part of the baby—the back and the back of the head—swing toward the front of your belly.

Key Actionable Takeaways:

- Monitor the kicks: Note where you feel the strongest movements. High-up kicks usually mean the baby is already head down.

- Ask for a check at 32-34 weeks: If your provider hasn't mentioned the position, ask them to feel for the head during your routine check-up.

- Use an exercise ball: Replace your office chair or sofa time with an anti-burst birth ball to keep your pelvis aligned.

- Stay hydrated: Amniotic fluid levels are crucial for baby's movement; keep those fluids up.

- Research ECV early: If your baby is breech at 35 weeks, read up on the risks and benefits of an External Cephalic Version so you aren't making a snap decision at 37 weeks.

- Trust the process: Remember that babies can flip even during early labor. Your body and your baby are a team, and they generally know the way out.

The wait for the "big flip" can be nerve-wracking, but it’s just one of the many ways your body prepares for the marathon of birth. Most babies get the memo eventually.