You probably think you know the answer to when did the united states become independent. It’s July 4, 1776. We set off fireworks, grill burgers, and wear obnoxious red, white, and blue outfits to celebrate that specific date. But if you asked a lawyer in 1776, or a British soldier in 1781, or a diplomat in 1783, you’d get wildly different answers. History isn't a single shutter click. It's a long, messy, and often confusing exposure.

Independence didn't happen because someone signed a piece of paper and everyone suddenly agreed the King was out of a job. It was a slow-motion breakup. Honestly, the "birthday" of the United States is more of a birth process that spanned nearly a decade.

The July 2nd Versus July 4th Debate

John Adams, a man who was rarely wrong in his own mind, actually thought we’d celebrate independence on July 2nd. That was the day the Continental Congress actually voted for the resolution of independence. He wrote to his wife, Abigail, predicting that July 2nd would be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. He envisioned pomp, shows, games, and bonfires.

He was off by two days.

The Declaration of Independence—the actual document—wasn't approved until July 4th. Even then, most delegates didn't put pen to paper until August. If we’re being technical about when did the united states become independent in a legal sense, the vote on the 2nd was the "yes," but the document on the 4th was the "press release."

Then you have the actual signing. Imagine the logistics of getting dozens of men, many of whom were dodging British warships, into one room to sign a document that was effectively a death warrant if they lost. It took months. Some people didn't sign until 1777.

When the World Actually Cared

Declaring you’re independent is one thing. Having the guy you're breaking up with acknowledge it is another. For Great Britain, July 4, 1776, was basically a nuisance. It was a tantrum by some colonies that needed to be suppressed.

The real shift happened at Yorktown. In October 1781, General Cornwallis surrendered. This is a massive turning point. Even though the war technically dragged on for a bit, this was the moment the dream became a reality. Yet, even then, the United States wasn't "independent" in the eyes of international law.

The Treaty of Paris (1783)

If you’re a stickler for international law, the answer to when did the united states become independent is September 3, 1783. This is when the Treaty of Paris was signed.

This was the formal "divorce decree." Great Britain finally admitted, in writing, that the United States were "free sovereign and independent states." Without this piece of paper, the U.S. was just a collection of rebels. With it, they were a nation. It’s a boring answer compared to fireworks and hot dogs, but it’s the legally accurate one.

The Sovereignty Gap

There’s also the issue of the Articles of Confederation. Between 1776 and 1789, the U.S. was barely a country. It was more like a loose club of thirteen grumpy neighbors who didn't want to pay for anything.

We had a "president" under the Articles, but he had no power. We had no tax system. We had no real army. Did independence count if the government couldn't even pay its own light bill? Some historians argue that the U.S. didn't truly become a functional independent power until the Constitution was ratified and George Washington took the oath in 1789. That’s a thirteen-year gap from the Declaration!

Why the Date Matters for Your Taxes (Really)

It sounds academic, but these dates have real-world consequences. Take land claims. If the U.S. became independent in 1776, then any land grants given by the King after that date were void. If it was 1783, those grants might still be valid. Courts had to untangle this mess for decades.

The Lee Resolution: The Forgotten Birthday

Before the famous Declaration, there was the Lee Resolution. Richard Henry Lee of Virginia proposed it on June 7, 1776. It was simple. It said the colonies "are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States."

📖 Related: The Cuban Missile Crisis: What Actually Happened During Those 13 Days

That was the spark.

Everything else—the soaring prose of Thomas Jefferson, the edits by Benjamin Franklin, the printing by John Dunlap—was just marketing. Jefferson was the writer, but Lee was the guy who pulled the trigger. We don't talk about Lee much because his resolution doesn't look as good on a poster as Jefferson's "Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness."

Common Misconceptions About the Timeline

People often think the Liberty Bell rang on July 4th and everyone in Philadelphia cheered. Sorta. The bell probably didn't ring that day, and many people in the colonies were actually terrified. About a third of the population were Loyalists. They didn't want independence. They wanted to stay British.

To them, the question of when did the united states become independent wasn't a celebration; it was a tragedy. They saw it as a collapse of law and order. Many of them eventually fled to Canada. If you go to Nova Scotia today, you’ll find descendants of people who thought July 4th was the worst day in history.

Another weird fact? Thomas Jefferson and John Adams both died on July 4, 1826. Exactly fifty years to the day after the Declaration was adopted. You couldn't write a more cinematic ending if you tried. It cemented the 4th as the "official" date in the American psyche, regardless of what the legal treaties said.

Evolution of the Celebration

We didn't even celebrate the 4th much at first. It was too partisan. During the 1790s, the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans had different ideas about what independence meant. One side loved the Declaration; the other side thought it was too radical.

It wasn't until after the War of 1812 that the 4th of July became the unifying national holiday we know today. We needed a common myth to hold the country together. By then, the nuances of 1783 or 1789 were pushed aside for the simpler, more heroic narrative of 1776.

How to Verify the Dates Yourself

If you want to go down the rabbit hole, you don't have to take my word for it. You can look at the primary sources.

- The Dunlap Broadsides: These are the first printed copies of the Declaration. Check the date on the top.

- The Journals of the Continental Congress: These records show the actual votes on July 2nd.

- The Treaty of Paris (Original Document): Look for Article 1. It’s where the King gives up his claim.

History isn't a static thing. It's a series of arguments that eventually settle into a story. The story says 1776. The law says 1783. The reality says it was a long, hard-fought transition.

Final Insights on American Independence

Understanding the timeline of American independence helps you see the country as an evolving project rather than a finished product that appeared out of thin air. It was a process of trial, error, and immense risk.

Next Steps for History Buffs:

- Visit the National Archives: If you're ever in D.C., go see the "Charters of Freedom." Seeing the actual ink on the parchment changes how you feel about the dates.

- Read the Lee Resolution: Compare it to Jefferson’s Declaration. It’s fascinating to see how the raw idea was polished into a philosophical masterpiece.

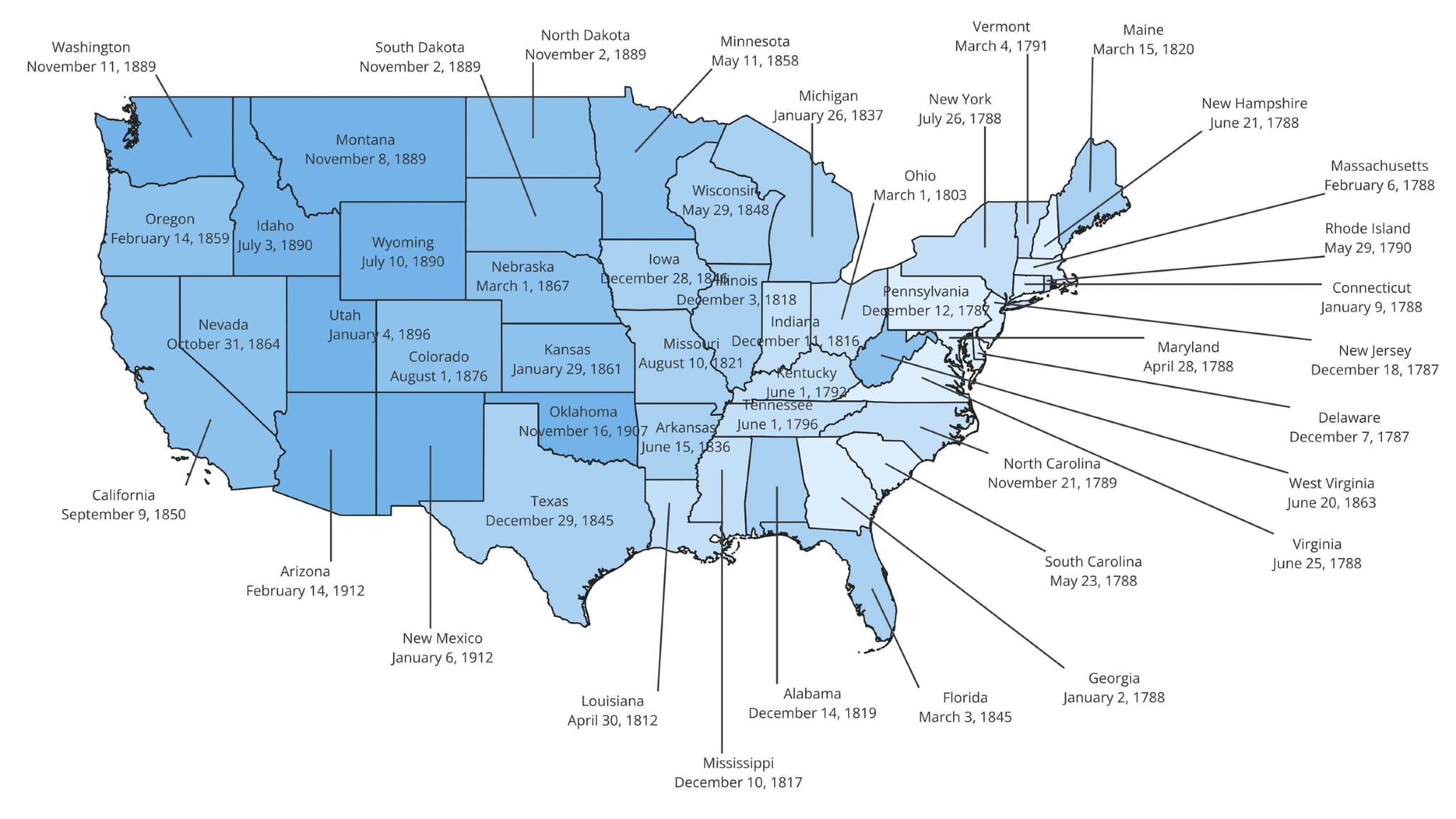

- Research the "State" Independence Dates: Remember, many colonies declared independence individually before the Continental Congress did. Rhode Island actually celebrates its own "Independence Day" on May 4th.

- Check the British Perspective: Look up the "Proclamation of Rebellion" issued by King George III in 1775. It shows that, in his mind, the war started way before we decided to write a document about it.

Independence is more than a day. It’s the result of years of debate, war, and eventual diplomatic recognition. While we’ll keep lighting fireworks on July 4th, knowing the full story makes the celebration a lot more meaningful.