If you ask most people when did the slaves get freed, you’ll usually get a one-word answer: 1863. Or maybe 1865. People like clean dates. We want history to have a "start" button and a "stop" button, but history is rarely that polite. Honestly, the end of slavery in the United States wasn't a single moment. It was a chaotic, bloody, and frustratingly slow grind that took years—decades, really—to actually take hold across the map.

It didn't just happen because a pen hit a piece of paper. It happened in fits and starts.

The Emancipation Proclamation was just the beginning

Let's talk about January 1, 1863. That’s the big one. Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, and on paper, it "freed" three million people. But there’s a massive "but" here. The Proclamation only applied to states that were currently in rebellion against the Union. Basically, if you were an enslaved person in a "Border State" like Kentucky, Delaware, Maryland, or Missouri—states that stayed with the North—Lincoln’s order didn't apply to you. You were still legally enslaved.

It’s kind of wild to think about. The very document we celebrate as the death knell of slavery actually left thousands of people in bondage because of political maneuvering. Lincoln needed those border states to win the war. He couldn't risk them flipping to the Confederacy. So, he made a deal.

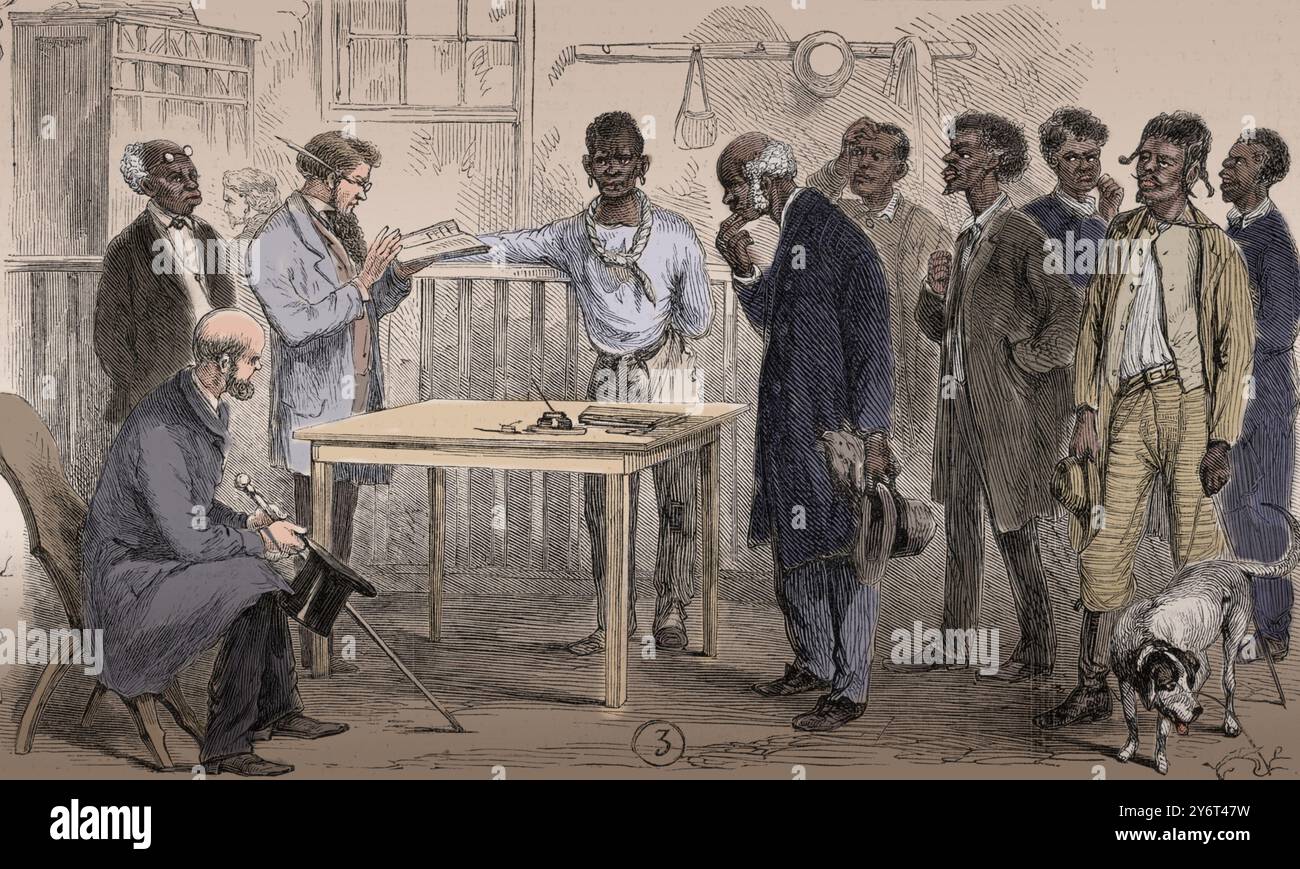

And even in the South? The Proclamation was mostly a piece of paper until a Union soldier showed up with a rifle to enforce it. For a lot of people, freedom didn't come in 1863. It came whenever the Northern army marched into their town. Sometimes that was months later. Sometimes years.

Juneteenth and the Texas delay

You’ve probably heard of Juneteenth by now. It’s finally a federal holiday, but for a long time, it was a piece of history that a lot of textbooks just skipped over.

On June 19, 1865, Union General Gordon Granger stood in Galveston, Texas, and read General Order No. 3. This was more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation. Two years. Imagine being legally "free" but working in a field for two extra years because nobody told you the rules had changed. Texas was the edge of the Confederacy, a place where many slaveholders moved specifically to get away from the Union army.

When Granger arrived, he basically told the people of Texas that the war was over and everyone was free. But even then, it wasn't like a switch flipped. Many plantation owners waited until after the harvest to tell their workers. Some didn't tell them at all until they were forced to by military patrols. Freedom was a rumor before it was a reality.

👉 See also: What Really Happened With the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz

The 13th Amendment: Closing the legal loopholes

If we're looking for the absolute legal answer to when did the slaves get freed, the real date is December 6, 1865. That’s when the 13th Amendment was officially ratified.

The Emancipation Proclamation was a wartime measure. There was a very real fear that once the war ended, the courts would rule it unconstitutional and everyone would be forced back into slavery. The 13th Amendment was meant to be the permanent fix. It abolished "slavery or involuntary servitude," except—and this is a huge exception—as punishment for a crime.

That "punishment for a crime" clause is something historians like Douglas A. Blackmon have written about extensively. It basically paved the way for "convict leasing," where Black men were arrested for things like "vagrancy" (basically being unemployed) and then sold back into forced labor for private companies. It’s a dark chapter that shows how "freedom" wasn't always what it seemed.

Why did it take so long?

It’s easy to look back and wonder why it was such a mess. Why didn't everyone just stop on one day?

Logistics. That’s the boring but honest answer. In the 1860s, news traveled at the speed of a horse. If you were on a remote plantation in Mississippi or Louisiana, you might not see a newspaper for weeks. And your "owner" certainly wasn't going to tell you that you were free to walk away.

There was also the sheer resistance of the Southern economy. The South was built on free labor. Taking that away meant a total collapse of their financial system. They fought it every inch of the way. Even after the 13th Amendment passed, many Black families found themselves trapped in "sharecropping" cycles that looked and felt a lot like the slavery they had supposedly escaped. They were "free," but they were in debt, they couldn't leave the land, and they had no political rights.

The role of Black soldiers in their own liberation

We can't talk about when did the slaves get freed without mentioning the people who actually did the freeing. It wasn't just white politicians in Washington.

✨ Don't miss: How Much Did Trump Add to the National Debt Explained (Simply)

By the end of the Civil War, nearly 200,000 Black men had served in the Union Army and Navy. When Black regiments marched into Southern towns, the message was clear. They were the physical embodiment of emancipation. For many enslaved people, seeing a Black man in a Union uniform with a gun was the first time they realized the world had actually changed.

Frederick Douglass famously argued that once a Black man had fought for his country, there was no way he could be denied his status as a citizen. He was right, eventually, but it was a long road to get there.

Freedom didn't mean equality

Here is the thing that’s hard to wrap your head around: being "freed" is not the same as being "free."

In 1865, four million people were suddenly no longer property. That’s incredible. It’s one of the greatest shifts in human history. But they were freed into a country that had no plan for them. No land. No money. No education. Most had nothing but the clothes on their backs.

The "Freedmen’s Bureau" was set up to help, but it was underfunded and constantly attacked by Southern politicians. Then came the "Black Codes"—laws specifically designed to restrict Black movement and labor. So, while the legal status of slavery ended in 1865, the struggle for actual, lived freedom continued through the Reconstruction era, the Jim Crow era, and right into the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s.

The specific timeline of emancipation

To make it easier to visualize, here is how the rollout actually looked on the ground. It wasn't a straight line.

In April 1862, slavery was abolished in Washington D.C. This was a huge deal. The government paid the slaveholders to let people go (compensation for the "loss of property"). It’s the only place in the U.S. where that happened.

🔗 Read more: The Galveston Hurricane 1900 Orphanage Story Is More Tragic Than You Realized

Then came the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863. It freed people in the "states in rebellion."

In 1864 and 1865, individual states started changing their own constitutions. Maryland freed its enslaved population in November 1864. Missouri followed in January 1865.

Then, the surrender at Appomattox happened in April 1865. The war was over, but the law hadn't caught up.

Finally, Juneteenth happened in Texas in June 1865, and the 13th Amendment was ratified in December 1865.

It was a three-year process of dismantling an institution that had existed for centuries. It was messy, it was violent, and it was incomplete.

What you can do with this history

Understanding when did the slaves get freed is about more than just memorizing a date for a history quiz. It’s about understanding the "how" and the "why." If you want to dive deeper, here are a few things you can actually do to engage with this history in a real way:

- Visit a Reconstruction site. Places like the Reconstruction Era National Historical Park in South Carolina show what life was like for the first generation of freed people. It’s eye-opening.

- Read the actual narratives. The Library of Congress has a massive collection of "Slave Narratives" recorded in the 1930s. These are first-hand accounts from people who were children when the war ended. Hearing them describe the day they "got free" is haunting and necessary.

- Research your local history. Slavery wasn't just a "Southern thing." Northern states had gradual emancipation laws that lasted well into the 1800s. Look up when the last enslaved person was legally freed in your specific state. You might be surprised.

- Follow the legal thread. Look into the 14th and 15th Amendments. Freedom was the first step, but citizenship and voting rights were the next battles. Understanding how those rights were given—and then systematically taken away—is key to understanding the U.S. today.

The end of slavery wasn't a gift. It was a hard-fought victory that took the lives of 600,000 soldiers and the courage of millions of enslaved people who risked everything to run toward the Union lines. When we ask when they were freed, the answer is that they started freeing themselves the moment the war began, and the law finally caught up in late 1865.