It was late. Most of the world was asleep while a crew of engineers at the Vladimir Ilyich Lenin Nuclear Power Plant—better known as Chernobyl—prepped for a safety test that should’ve been routine. But things went south fast. So, when did the Chernobyl nuclear accident happen? Exactly at 1:23:40 a.m. local time on April 26, 1986. That’s the precise moment Reactor 4 became a graveyard of twisted metal and radioactive dust.

It didn't just happen out of nowhere.

The disaster didn't start with a bang, but with a series of questionable decisions made during a night shift. If you've ever wondered why a simple test turned into the worst nuclear disaster in history, it’s basically because of a perfect storm of design flaws and human error. The operators were trying to see if the turbines could provide enough power to the cooling pumps during a blackout. Ironically, the "safety test" caused the explosion.

The Timeline of a Midnight Catastrophe

People often get the date right but miss the chaotic lead-up. The test was actually supposed to happen during the day on April 25. However, an electricity demand spike in Kiev meant the plant had to stay online. The day shift, who had been briefed on the test, went home. The evening shift took over, then eventually, the night shift. This meant the guys actually pushing the buttons at 1:23 a.m. weren't the ones who had prepared for it.

The power dropped too low. It became unstable.

Alexandr Akimov and Leonid Toptunov were in the control room. They were facing a "poisoned" reactor—an effect caused by a buildup of xenon-135 gas. Instead of shutting down, they pushed ahead. They pulled out almost all the control rods. This is like driving a car at 100 mph and realizing you've cut the brake lines. When they finally tried to hit the "AZ-5" button—the emergency shutdown—it was too late.

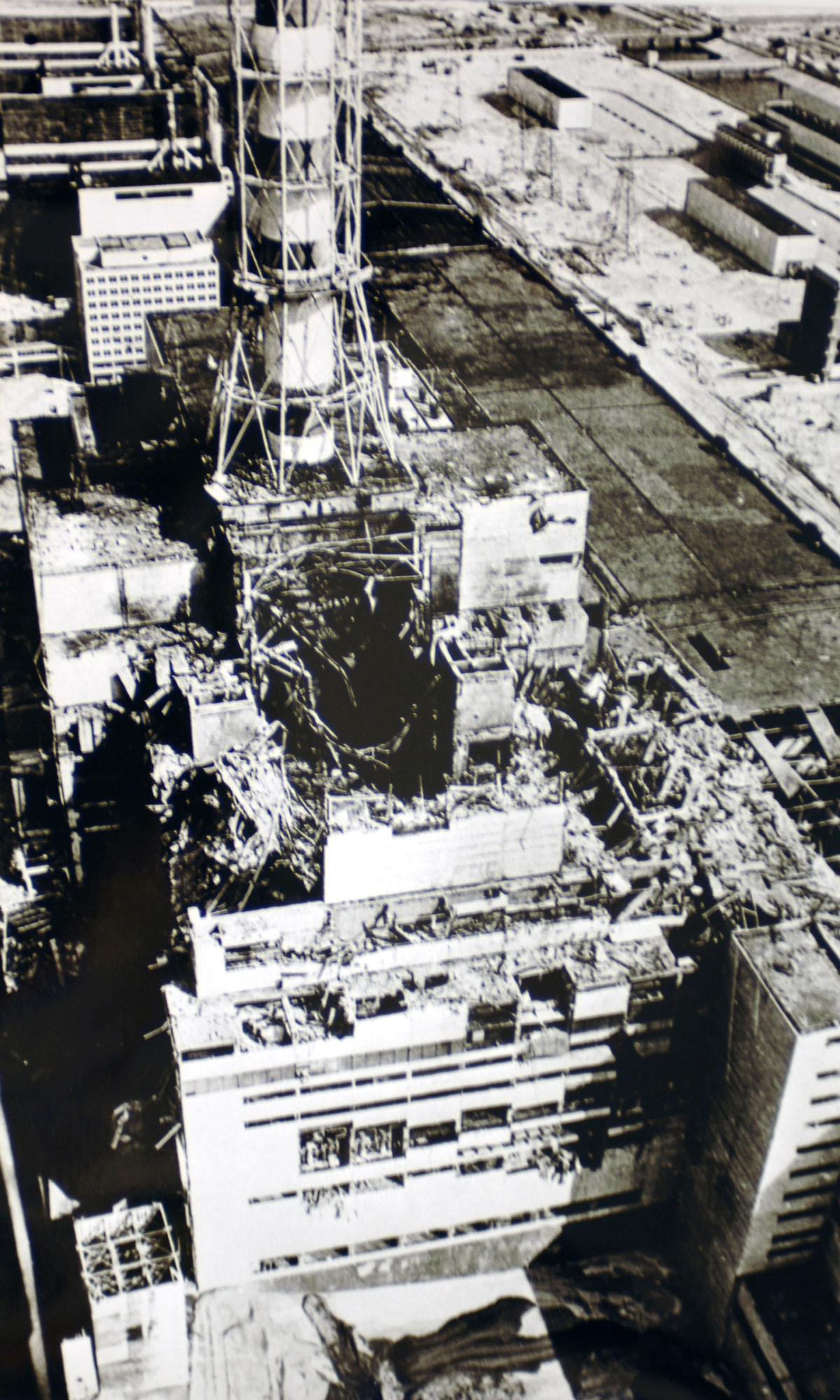

The graphite tips on the control rods actually caused a momentary increase in reactivity when they first entered the core. This is a design flaw unique to the RBMK reactor that the Soviet authorities knew about but hadn't fixed. Within seconds, the pressure built up. A steam explosion blew the 2,000-ton lid off the reactor. A second explosion followed shortly after.

Why the Soviet Response Was So Delayed

The world didn't find out immediately. Not even close.

The Soviet Union was a machine of secrecy. For the first few hours, even the guys in charge at the site didn't believe the core was gone. They thought it was just a fire. Firefighters like Vasily Ignatenko rushed to the roof of Reactor 3 to put out blazes, unaware they were standing in a lethal field of ionizing radiation.

Sweden was actually the one to tell the world something was wrong. On April 28, two days after the event, workers at the Forsmark Nuclear Power Plant in Sweden detected high levels of radiation on their shoes. They realized the leak wasn't coming from their plant; the wind was blowing it in from the USSR.

- April 26: The explosion occurs at 1:23 a.m.

- April 27: The nearby city of Pripyat is finally evacuated. 50,000 people are told to pack for three days. They never returned.

- April 28: The Soviet news agency TASS finally releases a short, five-sentence statement about an "accident" at Chernobyl.

- May 14: Mikhail Gorbachev gives a televised address to the nation, nearly three weeks late.

The delay was deadly. Because the government didn't immediately warn the public, children in the surrounding areas continued to play outside. They drank milk contaminated with radioactive iodine-131. This led to a massive spike in thyroid cancer cases in the following years. It's a grim reminder that when did the Chernobyl nuclear accident happen is only half the story; the silence after it happened was just as destructive.

The Liquidators: A Different Kind of War

You've probably heard of the "Liquidators." These were the roughly 600,000 people—soldiers, miners, and civilians—called in to clean up the mess. They were basically the world’s most desperate janitors.

Some had to shovel chunks of highly radioactive graphite off the roof of the reactor. They called themselves "bio-robots" because the actual electronic robots they tried to use kept frying due to the intense radiation. They could only stay on the roof for 40 to 90 seconds at a time. A few shovelfuls, and then your career—and sometimes your health—was over.

🔗 Read more: Sherrod Brown Polling: What Most People Get Wrong About the 2026 Ohio Senate Race

Valery Legasov, the lead scientist on the Chernobyl commission, fought an uphill battle to tell the truth about the design flaws. His tapes, recorded before his suicide in 1988, served as a whistleblowing account that eventually forced the Soviet Union to admit the RBMK reactors were dangerous. It’s heavy stuff. Honestly, the bravery of these people is the only reason the rest of Europe didn't become an uninhabitable wasteland.

Long-Term Health and the Exclusion Zone

What’s it like there now? The 30-kilometer Exclusion Zone is a weird time capsule.

Nature has reclaimed Pripyat. Wolves, bears, and wild horses roam the streets where Soviet parades used to happen. While the radiation has dropped significantly, some areas are still "hot" enough to be dangerous if you hang out too long. The "Elephant's Foot"—a mass of corium (melted fuel and concrete) in the basement—is still one of the most toxic things on Earth.

Health-wise, the numbers are still debated. The Chernobyl Forum, a group involving the WHO and IAEA, suggests a total death toll in the thousands due to long-term cancers. Other organizations like Greenpeace argue the number is much higher, potentially in the tens of thousands, when you factor in the broader European population. The psychological trauma of forced relocation is a whole other layer of the tragedy that experts say is often overlooked.

Lessons That Changed Nuclear Power Forever

Because of what happened on that April night in 1986, the nuclear industry underwent a massive cultural shift. It wasn't just about hardware; it was about "Safety Culture."

The RBMK design was overhauled. Western reactors, which mostly use containment buildings (something Chernobyl lacked), re-verified their safety protocols. We learned that you can't prioritize production quotas over safety margins. It’s a lesson that cost a lot of lives.

If you're looking to understand the timeline or the impact of this event, you have to look at it as a failure of systems, not just a failure of people. When did the Chernobyl nuclear accident happen? It happened when a culture of secrecy met a flawed machine.

Actionable Steps for Understanding the Context

To get a full grasp of the scope and history beyond the date, here are the most effective ways to research the nuanced details of the 1986 disaster:

- Read the Legasov Tapes: Search for the transcripts of Valery Legasov’s accounts. They provide the most direct insight into the technical and political failures that led to the explosion.

- Consult the UNSCEAR Reports: For the most scientifically accurate, non-sensationalized data on radiation health effects, the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) is the gold standard.

- Use Satellite Mapping: View the Exclusion Zone via Google Earth to see the "New Safe Confinement" structure. This massive silver arch was slid into place in 2016 to seal the reactor for at least the next 100 years.

- Study the RBMK Design: Look up the "positive void coefficient" flaw. Understanding this specific engineering quirk explains why the reactor accelerated when it should have slowed down.

- Explore Oral Histories: Svetlana Alexievich’s book Voices from Chernobyl offers a collection of first-hand accounts from survivors, providing the human perspective that technical reports often omit.

The events of April 26, 1986, remain the benchmark for industrial accidents. By looking at the specific timeline and the subsequent cover-up, it becomes clear that the disaster was not a single moment in time, but a cascading failure that began years before the first spark and continues to affect the landscape today.