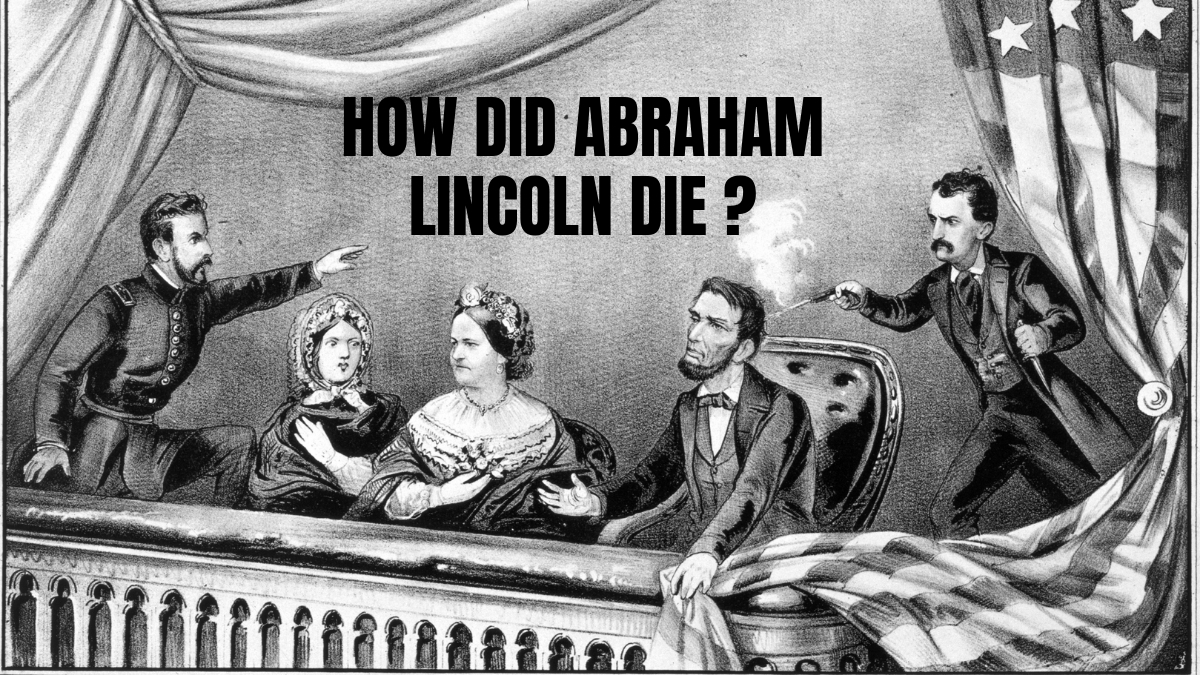

You’ve seen the grainy photos and the tall top hat. Most of us have the basic "history book" version of the story down: a theater, a gunshot, a tragic end. But honestly, the specific timeline of when did Lincoln die is a lot messier and more agonizing than a single date on a timeline suggests. It wasn't just a moment in time. It was a nine-hour medical battle that unfolded in a cramped, musty bedroom while a nation literally held its breath.

Abraham Lincoln died at 7:22 a.m. on Saturday, April 15, 1865.

That’s the hard fact. But the "when" of it actually starts the night before. On April 14, Good Friday, the Civil War was basically over. The mood in Washington was electric. People were celebrating. Lincoln, looking for a rare moment of peace, headed to Ford’s Theatre to see a comedy called Our American Cousin. He didn’t even want to go at first, but his wife, Mary, insisted because it had been advertised that the President would be there.

📖 Related: The Fall of Kabul: Why the World Was Caught So Off Guard

He was shot at approximately 10:15 p.m.

The Longest Night on 10th Street

The bullet from John Wilkes Booth's .44-caliber Derringer entered through Lincoln's left ear and lodged behind his right eye. He didn't die instantly. In fact, if you were in that theater, you might have thought he was already gone. He slumped forward, his breathing became labored, and the chaos began.

Doctors in the audience rushed to the state box. Dr. Charles Leale was the first on the scene. He realized quickly that the President wouldn't survive a carriage ride back to the White House. The roads were too bumpy, and the internal pressure in Lincoln's brain was too great. They needed a bed, and they needed it fast.

Soldiers and bystanders carried Lincoln’s unconscious body out of the theater and across 10th Street. A boarder at the Petersen House, a man named Henry Safford, stood on the front steps with a candle, shouting, "Bring him in here!"

They laid him in a small back bedroom on the first floor.

Here’s a detail that’s kinda heartbreaking: Lincoln was 6'4". The bed was too small. The soldiers actually had to lay him diagonally across the mattress just so his legs wouldn't hang off the end. For the next nine hours, that tiny room became the center of the American universe.

Medical Reality vs. Modern Myth

A common question people ask is whether modern medicine could have saved him. Honestly, probably not. The bullet had traveled through the brain's left hemisphere, crossed the midline, and caused massive hemorrhaging. Even today, a wound like that is a "mortal" injury.

Throughout the night, the doctors performed a gruesome but necessary task. They periodically cleared blood clots from the entry wound to relieve pressure on the brain. Every time they did, his breathing would become "as sweet and regular as an infant," according to Dr. Robert King Stone. But it was a temporary fix.

📖 Related: Wake Forest Police Scanner: Why Tuning In Still Matters for Town Safety

The room was packed. At one point, over 20 people were squeezed into that 9-by-17-foot space. Cabinet members, physicians, and Robert Lincoln (the President's eldest son) kept watch. Mary Todd Lincoln, however, spent most of the night in the front parlor, overwhelmed by grief. She was only brought in a few times, as her distress was so intense it was difficult for the doctors to work.

The Moment the Clock Stopped

As dawn broke on April 15, the President’s pulse began to fail. His breathing became a series of gasps.

At 7:22 a.m., the room went silent.

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton supposedly uttered the famous line: "Now he belongs to the ages." Some historians argue he actually said "angels," but "ages" is what stuck in the history books.

Vice President Andrew Johnson was sworn in as the 17th President just a few hours later, at 11:00 a.m., in his rooms at the Kirkwood House. The transition of power happened while the city was still draped in the flags that had been put up for the victory celebrations just days earlier.

Common Misconceptions About Lincoln's Death

You'd be surprised how many "facts" about Lincoln's passing are actually myths.

- The Lincoln Memorial Grave: A lot of people think Lincoln is buried under the Lincoln Memorial in D.C. He isn't. He’s buried in Springfield, Illinois, at Oak Ridge Cemetery. The memorial is just that—a memorial.

- The "Instantly Dead" Theory: Because he never regained consciousness, people often think he died at the theater. He didn't. He survived for over nine hours after being shot.

- The Funeral Train: People sometimes forget that the mourning period lasted for weeks. His body traveled 1,600 miles through 180 cities on a funeral train so the public could pay their respects.

Why the Timing Mattered

The fact that Lincoln died when he did—on the heels of the Union victory and at the very start of Reconstruction—changed everything. He had a plan for "charity for all" to bring the South back into the fold. His successor, Andrew Johnson, didn't have the same political capital or temperament.

Basically, the timing of when did Lincoln die created a massive power vacuum that arguably led to decades of additional strife during the Reconstruction era.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you want to experience this history beyond a textbook, there are a few things you should actually do:

👉 See also: Lake Placid Police Department FL: What Residents and Visitors Actually Need to Know

- Visit the Petersen House: It’s still there in D.C., across from Ford’s Theatre. You can stand in the very room where he died. It’s hauntingly small and gives you a real sense of the claustrophobia of that night.

- Check the National Museum of Health and Medicine: They actually have the lead ball (the bullet) that killed him, along with fragments of his skull. It’s in Silver Spring, Maryland.

- Read the Eyewitness Accounts: Look up the diary of Gideon Welles, the Secretary of the Navy. His description of the night is incredibly vivid and far more personal than any Wikipedia entry.

The story of Lincoln's death isn't just about a date in 1865. It's about a man who lived just long enough to see his country survive, but not long enough to help it heal. Understanding the "when" helps us understand the "why" of the century that followed.