Ever felt like the calendar is lying to you? It kinda is. We’re taught from kindergarten that every four years, we tack an extra day onto February to keep the seasons from drifting into chaos. Simple, right? Except it isn’t. If you think every year divisible by four is a leap year, you’re going to be very confused when the turn of the next century rolls around.

The truth is that what years are leap years depends on a set of rules established back in 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII. Before that, the Julian calendar—the one Julius Caesar championed—was making a mess of things. It assumed the earth takes exactly 365.25 days to orbit the sun. It doesn’t. It takes about 365.2422 days. That tiny difference of eleven minutes a year doesn't sound like much, but over centuries, the dates of the spring equinox started sliding backward. By the 1500s, Easter was happening at the wrong time. The Pope had to fix it, or the whole liturgical year would have collapsed into seasonal nonsense.

The Triple Rule for Identifying a Leap Year

Basically, you have to pass three tests to know if a year gets that extra 29th day in February. Most of us only know the first one.

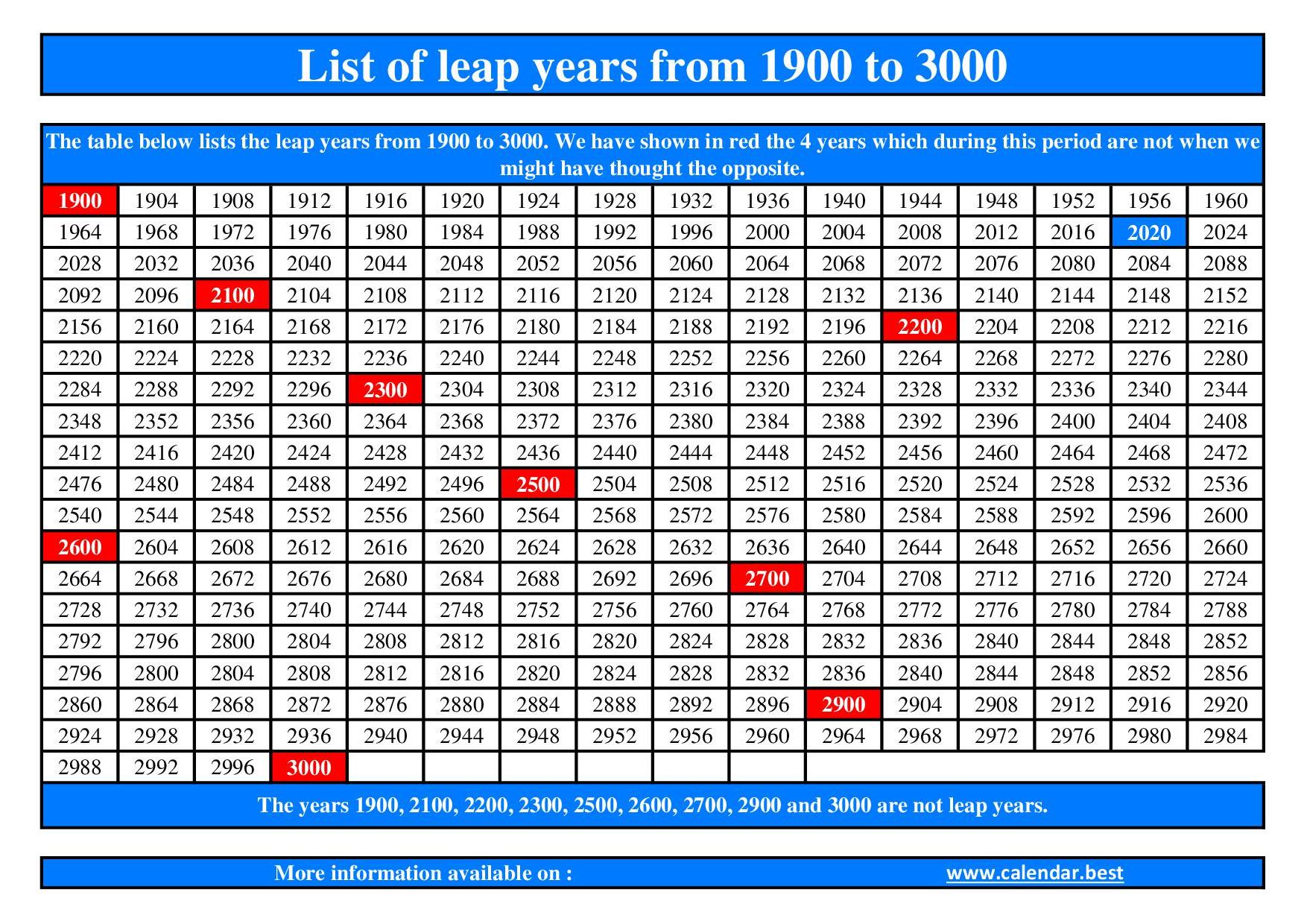

First, the year must be evenly divisible by four. This is the rule everyone remembers. 1996? Yes. 2020? Yes. 2024? Obviously. But here is where it gets weird. If a year is divisible by 100, it is not a leap year—unless it is also divisible by 400.

Think about that for a second. It means the year 1900 was not a leap year. The year 2100 won't be one either. However, the year 2000 was a leap year because it hit that "divisible by 400" exception. Most people living today only remember 2000, so they assume all century years are leap years. They aren't. We just happened to live through the one exception to the rule. If you're still around in 2100, you’ll notice February ends on the 28th, even though 2100 is divisible by four.

Why We Need an Intercalary Day Anyway

Space is messy. The universe doesn't care about our neat 24-hour cycles or our 365-day grids. Astronomers call the time it takes for Earth to complete one orbit a "tropical year." If we didn't add leap days, our calendar would drift by about 24 days every century.

Imagine July in the Northern Hemisphere slowly becoming a winter month. It would take about 700 years, but eventually, you'd be building snowmen in the middle of summer. Farmers would lose track of when to plant crops. The entire infrastructure of human civilization relies on the calendar matching the actual position of the sun.

We use the term "intercalary" to describe these inserted days. It’s a fancy word for a "gap-filler." Without that filler, the solar year and the calendar year would grow further apart until the names of the months meant nothing relative to the weather outside your window.

The 2000 vs. 2100 Confusion

I’ve talked to people who are convinced the "divisible by 100" rule is a myth. They point to the turn of the millennium. "I was there in 2000," they say, "and we definitely had a February 29th."

They’re right. But 2000 was a rare "Leap Century." Because 2000 is divisible by 400 ($2000 / 400 = 5$), it kept the leap day. The next time this happens is the year 2400. For anyone born after 2000, the first "skipped" leap year they will experience is 2100. It’s a long wait for a math correction.

Other Calendars Do It Differently

We aren't the only ones trying to solve the "messy orbit" problem. The Revised Julian Calendar, used by some Orthodox churches, is actually more accurate than the Gregorian one we use for secular business. It uses a cycle of 900 years instead of 400. In their system, a century year is only a leap year if the remainder is 2 or 6 when divided by 9. It’s significantly more complex but stays in sync with the sun for thousands of years longer.

Then you have the Iranian (Persian) calendar. It’s arguably the most beautiful system because it’s based on astronomical observations rather than mathematical rules. They check when the vernal equinox actually happens in Tehran. If the sun crosses the equator before noon, that day is New Year. It’s incredibly precise because it adjusts to the Earth's slightly fluctuating rotation speed in real-time.

The "Leap Second" Controversy

While we're talking about what years are leap years, we should probably mention leap seconds. The Earth's rotation is actually slowing down very gradually because of tidal friction caused by the moon. To keep our ultra-precise atomic clocks aligned with the Earth's physical rotation, scientists have been adding "leap seconds" since 1972.

Tech companies hate this.

When you add a second to a global network of computers, things break. Google, Meta, and Amazon have all pushed to get rid of the leap second because it causes "smearing" issues in databases and time-stamped transactions. In late 2022, international scientists actually voted to scrap the leap second by 2035. We’re going to let the gap grow for a while and then maybe add a "leap minute" later in the century. It’s a practical solution to a digital headache.

Practical Ways to Check Any Year

If you're ever in a trivia contest or just trying to program a spreadsheet, here is the mental flowchart you need.

👉 See also: Megachurch Pastor Private Jets: Why the Controversy Never Actually Ends

- Is the year divisible by 4? If no, it’s a common year.

- If yes, is it divisible by 100? If no, it’s a leap year.

- If yes, is it divisible by 400? If yes, it’s a leap year. If no, it’s a common year.

Let's test it on the year 1800. Divisible by 4? Yes ($450$). Divisible by 100? Yes ($18$). Divisible by 400? No ($4.5$). So, 1800 was not a leap year.

What about 2028? Divisible by 4? Yes ($507$). Divisible by 100? No. Boom. It’s a leap year.

Why February?

It seems cruel to give the shortest month the extra day. Why not give it to June? Or August?

Blame the Romans. In the original Roman calendar, the year started in March. February was the last month of the year. When you have to add an extra day to keep things balanced, you usually tack it onto the end. Even after the calendar was reorganized to start in January, February kept its status as the "adjustable" month.

Interestingly, for a long time, the leap day wasn't even February 29th. The Romans used to "double" the sixth day before the Kalends of March. They literally had two days with the same date. It wasn't until later that the modern 1-29 numbering became the standard.

The Cultural Weight of the Leap Day

There’s a lot of folklore attached to these years. You’ve probably heard the tradition that women are "allowed" to propose to men on February 29th. This supposedly traces back to an agreement between Saint Bridget and Saint Patrick in 5th-century Ireland, though most historians think it's a much later invention.

In some cultures, like in Greece, getting married in a leap year is actually considered bad luck. One in five engaged couples in Greece will reportedly avoid a leap year for their wedding date.

Then there are the "leaplings"—people born on February 29th. The odds of being born on a leap day are about 1 in 1,461. Famous leaplings include motivational speaker Tony Robbins and rapper Ja Rule. Legally, most countries consider their birthday to be February 28th or March 1st in non-leap years for things like driver's licenses and drinking ages.

Actionable Steps for Managing Leap Years

If you are a developer, business owner, or just a planner, you need to account for these calendar quirks.

Update Your Software Logic

Don't write custom code for leap years. Use standard library functions like DateTime.IsLeapYear in .NET or calendar.isleap() in Python. DIY date math is the number one cause of "Y2K-style" bugs in modern apps.

Review Long-term Contracts

If you have a contract that pays out "daily" or "monthly," check how the 366th day is handled. In banking, some interest calculations use a 360-day year (the "Banker's Year"), while others use the actual 365 or 366. This can actually change the amount of interest you owe or earn.

Check Your Anniversary or Birthdays

If you have an event on February 29th, decide now which day you celebrate on common years. Most people pick March 1st because they feel like they "weren't born yet" on the 28th. Whatever you choose, stay consistent for legal documentation.

The calendar is a human invention trying to map a chaotic celestial dance. Understanding what years are leap years is basically just acknowledging that our 24-hour clocks aren't quite in sync with the stars. We’re always just playing catch-up with the sun.

To keep your personal records accurate, ensure any recurring four-year tasks—like renewing certain professional certifications or long-term battery replacements in safety equipment—are scheduled by the number of days elapsed rather than just the date, especially when crossing a century year like 2100. For most of us, though, just remember: if it’s divisible by four, it’s probably a leap year, but if it ends in "00," you better double-check the math.