If you walk into the Musée Picasso in Paris, you aren't just looking at paintings. You’re looking at a diary of a man who couldn't stop moving. Most people think of him as "the Cubist guy." That's a mistake. Honestly, calling Pablo Picasso a Cubist is like calling Prince a "guitar player"—it's technically true, but it misses the entire point of what was actually happening.

So, what type of artist was Picasso?

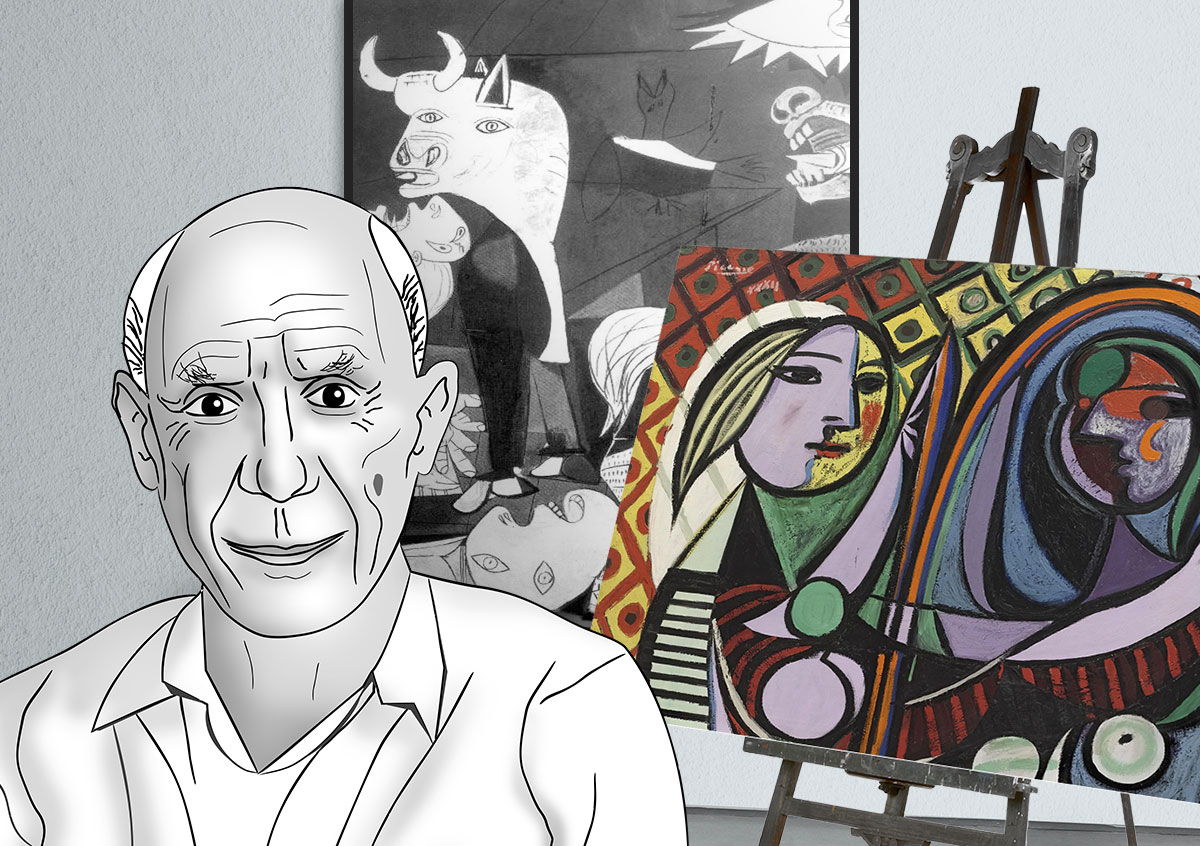

He was a shapeshifter. A restless, often problematic, and intensely prolific polymath who redefined the very idea of what an artist is supposed to do. He didn't just paint; he sculpted, he made ceramics, he wrote poetry, and he essentially invented the "artist as a celebrity" brand long before Andy Warhol ever touched a soup can.

The Stylistic Chameleon

The biggest misconception about Picasso is that he had one "look." He didn't. He had dozens.

If you look at his early work, like The First Communion, he was a traditionalist. He mastered the rules of classical realism by the time he was a teenager. His father, José Ruiz y Blasco, was a formal art teacher, and the young Pablo was so good so early that legend says his father gave up painting because his son had already surpassed him.

But Picasso got bored. He started moving through "periods" like most people move through outfits.

The Blues and the Roses

First, you've got the Blue Period (1901–1904). This wasn't just a color choice; it was a state of mind. Triggered by the suicide of his close friend Carles Casagemas, Picasso painted the outcasts of society—the blind, the poor, the lonely. Everything was soaked in monochromatic blues and greens. It was depressing, haunting, and notably, it didn't sell very well at the time.

Then things shifted. He met Fernande Olivier, he started feeling a bit better, and we got the Rose Period (1904–1906). The palette warmed up to oranges and pinks. He became obsessed with saltimbanques—circus performers. It was softer, sure, but it still felt distant.

👉 See also: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

Breaking the World with Cubism

Then 1907 happened. Les Demoiselles d'Avignon changed everything.

This is where the answer to what type of artist was Picasso gets complicated. Along with Georges Braque, he pioneered Cubism. They decided that the traditional perspective—the "window on the world" style used since the Renaissance—was a lie. Why should a painting only show one side of a face? Why not show the front, the side, and the back all at once?

They broke objects into geometric shards. It was radical. It was ugly to many. It was also the birth of modern art as we know it.

He Was a "Thief" of Genius

Picasso famously (or infamously) said that good artists borrow, but great artists steal. He wasn't talking about plagiarism; he was talking about influence.

He was a synthetic artist. He took inspiration from everywhere. He looked at African masks (which heavily influenced the distorted faces in his Cubist work), Iberian sculpture, and the Old Masters like Velázquez and Goya. He would take an idea, chew it up, and spit it out as something entirely "Picasso."

He was also a multimedia pioneer. While his contemporaries were sticking to oil on canvas, Picasso was gluing bits of newspaper and oilcloth onto his work. He basically invented collage as a fine art form. Later in life, he moved to Vallauris in the South of France and became a master of ceramics, producing thousands of plates, jugs, and tiles. He didn't believe in the hierarchy of art. To him, a clay pot was just as much a "Picasso" as a mural-sized canvas.

The Political Provocateur

For a long time, Picasso stayed out of politics. He lived through World War I without getting involved. But the Spanish Civil War changed him.

✨ Don't miss: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

When the Nazi-backed forces bombed the town of Guernica in 1937, Picasso didn't just write a letter of protest. He painted Guernica.

It’s a massive, monochrome nightmare of a painting. It doesn't show bombs or planes. Instead, it shows a screaming mother, a wounded horse, and a fallen soldier. It became the most powerful anti-war statement in history. When a Nazi officer allegedly saw a photo of the painting in Picasso’s Paris apartment and asked, "Did you do that?" Picasso reportedly replied, "No, you did."

He was an artist of engagement. He used his fame as a shield and a megaphone. Even during the Nazi occupation of Paris, he stayed in the city. He wasn't allowed to exhibit, but he kept working in his studio, a silent, stubborn symbol of resistance.

The Reality of the "Picasso Brand"

We have to be honest here. Picasso was a disruptor, but he was also a narcissist.

His personal life was a wrecking ball. He had two wives, many mistresses, and four children. His relationships were often characterized by a power dynamic that favored his creative needs over the mental health of the women in his life.

Art historians today, like Françoise Gilot (the only woman who ever left him) or biographers like John Richardson, highlight this complexity. You can't separate the artist from the man, but you also can't deny that his chaotic personal life fueled his creative output. Every time he changed women, he changed his style. The "Minotaur" became his alter ego—a beast that was both powerful and pathetic.

Prolific Beyond Belief

According to the Guinness World Records, Picasso was the most prolific painter in history.

🔗 Read more: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

- 13,500 paintings and designs

- 100,000 prints and engravings

- 34,000 book illustrations

- 300 sculptures and ceramics

He was a worker. He didn't wait for "inspiration" to strike. He went to the studio every single day. He once said, "Inspiration exists, but it has to find you working."

Why He Still Matters Today

So, really, what type of artist was Picasso? He was the first truly modern artist.

Before him, art was about representation. After him, art was about expression. He proved that an artist could be a brand, a political force, and a constant innovator. He taught us that "mastery" isn't a destination—it's just a tool you use until you find a better one.

If you’re trying to understand his impact, don't look for a specific technique. Look for the freedom. He gave every artist who followed him permission to change their minds. He made it okay to be inconsistent.

Actionable Insights for Art Lovers

If you want to truly "get" Picasso, stop trying to find the "hidden meaning" in his abstract shapes. Instead, try these steps:

- Look at the line work first. Even in his most distorted Cubist pieces, Picasso’s draftsmanship is incredible. Trace the lines with your eyes; you'll see the confidence of a man who knew exactly where the brush was going.

- Compare the periods. Pick a "Blue Period" work and a "Late Period" work side by side. Notice how he went from tight, controlled misery to loose, almost "childlike" scribbles. He famously said it took him four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.

- Visit the specific museums. Don't just go to the MoMA. Go to the Museu Picasso in Barcelona to see his early genius, or the Musée Picasso in Paris for his personal collection.

- Read "Life with Picasso" by Françoise Gilot. It’s the best way to understand the human being behind the myth, written by someone who actually lived with the "Minotaur."

- Acknowledge the evolution. Don't feel pressured to like everything he did. Many people love the Blue Period but find his late 1960s work messy and rushed. That's fine. The point of Picasso is the journey, not just the individual destination.

Picasso wasn't just a painter. He was a force of nature that happened to use a brush. He was an experimentalist who never stopped asking "What if?" and that, more than any specific style, is the definition of the type of artist he was.