Everyone thinks they know the story. Two guys from Ohio who owned a bike shop, a windy hill in North Carolina, and suddenly, humanity is flying. It sounds like a fable. But honestly, if you look at what the Wright brothers did, the "flying" part was almost the least interesting thing about their work.

They weren't just lucky tinkerers. They were obsessed.

Before Orville and Wilbur ever touched the sand at Kitty Hawk, the world was full of "aviators" who were essentially jumping off cliffs with giant umbrellas. Most of them died. Or they crashed immediately. The Wrights didn't want to just get into the air; they wanted to stay there. They figured out that the secret to flight wasn't actually wings. It was control.

The Myth of the Engine

Most people assume the big breakthrough was the engine. It makes sense, right? You need power to push a heavy machine into the sky. But the truth is much grittier. In 1903, nobody could build an engine light enough and powerful enough for what they needed. So, they didn't wait. They built their own.

Their mechanic, Charlie Taylor, is the unsung hero here. Together, they hammered out a four-cylinder aluminum block engine in about six weeks. It was crude. It vibrated like crazy. But it worked.

💡 You might also like: Why Does Wikipedia Ask For Money? The Real Reason Your Screen Is Full Of Banners

However, even with that engine, they would have crashed and burned—literally—if they hadn't solved the three-axis control problem. This is the absolute core of what the Wright brothers did that changed everything. Think about a bird. A bird doesn't just flap its wings to go up; it twists them. It tilts. Wilbur realized this while fiddling with a cardboard inner tube box in their bicycle shop in Dayton. He twisted the box, and the "wing warping" concept was born.

Why the Wind Tunnel Changed Everything

By 1901, the brothers were actually ready to quit. They had followed the "expert" data of the time—specifically the lift tables created by German pioneer Otto Lilienthal—and their gliders kept failing. They were frustrated. They felt like the math was lying to them.

"Man will not fly for fifty years," Wilbur famously said in a fit of pique.

He was wrong, but only because they decided to stop trusting everyone else. They built a six-foot-long wooden box with a fan—one of the first wind tunnels. They tested hundreds of miniature wing shapes (airfoils). They discovered that the existing scientific data was deeply flawed. By measuring the lift and drag of different shapes themselves, they became the first true aeronautical engineers in history. They stopped guessing.

December 17, 1903: 12 Seconds That Mattered

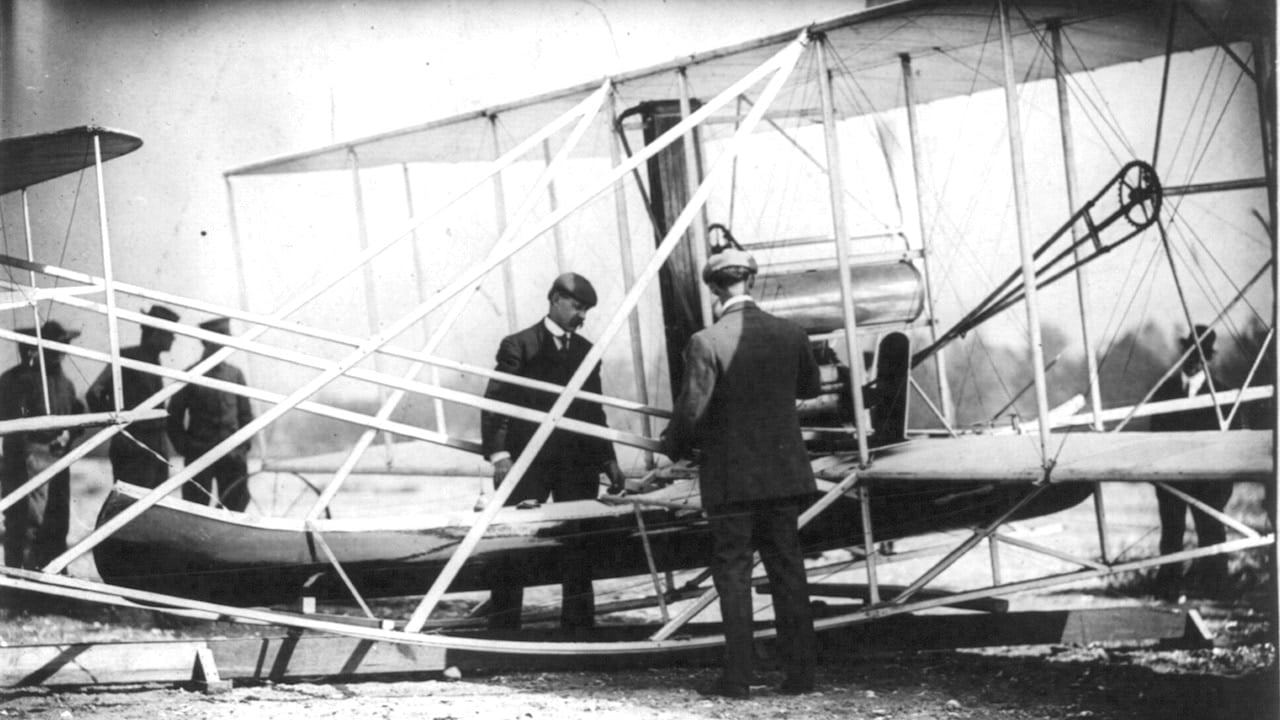

Kitty Hawk was miserable. It was cold. The sand got into everything. They lived in a shack that leaked. On the morning of December 17, it was freezing, and the wind was howling at over 20 miles per hour.

Orville took the first turn.

The Flyer moved down the rail. It took off. It lasted 12 seconds and covered 120 feet. It wasn't a majestic soar; it was a jerky, terrifying hop. But it was sustained. It was powered. It was controlled. By the end of the day, Wilbur managed a flight of 59 seconds, covering 852 feet.

📖 Related: Alexandr Wang and Scale AI: Why Data Labeling Became a National Security Asset

Imagine being there. There were only a few witnesses—mostly local men from the Kill Devil Hills Life-Saving Station. They weren't seeing a miracle; they were seeing the result of three years of grueling, mathematical failure.

The Bicycle Connection

You can't talk about what the Wright brothers did without talking about bikes. It sounds like a fun piece of trivia, but it’s the reason they succeeded where wealthy, government-funded scientists like Samuel Langley failed.

Bicycles are inherently unstable.

If you stop pedaling a bike, you fall over. You have to constantly balance it. This was their "Aha!" moment. Other inventors were trying to build "inherently stable" planes that would fly like a boat on water. The Wrights realized a plane should be like a bicycle—unstable by design, but controlled by the pilot. This shift in philosophy is why we have modern aviation. We don't want planes that just float; we want planes we can steer.

The Patent Wars and the Dark Side of Innovation

Success wasn't all parades and medals. Actually, it was mostly lawsuits.

📖 Related: Head Up Display HUD Technology: Why Most Drivers Are Still Using It Wrong

The Wrights became incredibly protective—some would say paranoid—about their wing-warping patent. They spent years suing other aviators like Glenn Curtiss. While the rest of the world (especially France) was taking their ideas and rapidly improving them, the Wrights were stuck in courtrooms.

It’s a bit of a tragedy. The very thing that made them great—their singular, obsessive focus—eventually slowed down their own innovation. By the time World War I rolled around, American aircraft design was actually lagging behind Europe because the legal battles had stifled collaboration.

Why Kitty Hawk Still Matters Today

When you look at a Boeing 787 or a fighter jet, you are looking at the direct descendants of that 1903 Flyer. The three axes of flight—pitch, roll, and yaw—are exactly the same principles the Wrights mapped out in their Dayton shop.

They didn't just "invent the airplane." They invented the science of flight.

They proved that systematic experimentation beats raw intuition every single time. They didn't have a college degree between them, but they out-thought the Smithsonian.

How to Apply the Wright Brothers' Mindset to Your Life:

- Question the "Proven" Data: If your project isn't working, don't assume you're the problem. The "industry standards" or "expert tables" you’re following might be wrong. Build your own wind tunnel. Test your own assumptions.

- Embrace Instability: Don't try to make your business or project perfectly safe and "stable" from day one. Build in mechanisms for control and adjustment instead.

- Focus on the Invisible: The engine is flashy, but the control system is what keeps you in the air. Focus on the underlying architecture of your work, not just the "power" behind it.

- Iterate in Small Steps: The Wrights didn't start with an engine. They started with kites. Then gliders. Then powered flight. Master the balance before you add the motor.

If you want to see the real deal, don't just look at photos. If you ever find yourself in Washington D.C., go to the National Air and Space Museum. Stand under the 1903 Flyer. It’s bigger than you think, made of wood and muslin, and it looks incredibly fragile. But it’s the most solid piece of history we have.

Next Steps for History Buffs:

Check out the Library of Congress digital archives for the Wright Brothers' actual diaries and telegrams. Reading Wilbur's handwritten notes about the 1903 flight provides a raw, unedited look at the moment the world changed. You can also visit the Wright Brothers National Memorial in Kill Devil Hills, NC, to walk the actual distance of those first four flights—it puts the scale of their achievement into a perspective that books simply can't capture.