"Feed your head."

It’s the most famous directive in psychedelic rock history. Grace Slick belts it out at the end of "White Rabbit" like a drill sergeant from a neon-soaked dimension. But if you actually go back to the source—Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland—you realize something weird. The Dormouse never actually says those words. Not exactly.

The Dormouse is a sleepy, marmalade-obsessed rodent. He’s stuck in a perpetual tea party with a Mad Hatter and a March Hare. Honestly, he’s basically the most relatable character in the book if you’ve ever had a Monday morning. People get the lyrics and the literature mixed up constantly, but that’s the beauty of how "What the Dormouse Said" became a cultural shorthand for the 1960s counterculture.

The Jefferson Airplane Twist

When Jefferson Airplane released Surrealistic Pillow in 1967, they weren't just making music. They were building a bridge between Victorian nonsense and the Haight-Ashbury drug scene. Grace Slick wrote "White Rabbit" after an acid trip while listening to Miles Davis’s Sketches of Spain. She wanted to point out that parents who read Alice in Wonderland to their kids were basically reading them a roadmap for hallucinogenic experimentation.

The song ends with that iconic repetition: "Remember what the dormouse said: Feed your head. Feed your head!"

But look at the text. In the book, the Dormouse mostly talks about three sisters living at the bottom of a treacle well. They were learning to draw everything that begins with an "M"—like mousetraps, and the moon, and memory, and muchness. He’s barely conscious. The "feed your head" line is Slick’s own invention, an interpretation of Alice’s journey where consuming things (mushrooms, cakes, potions) leads to an expansion of the mind. It’s a call to arms for intellectual and sensory curiosity.

🔗 Read more: Drunk on You Lyrics: What Luke Bryan Fans Still Get Wrong

What Actually Happened at the Tea Party

If we’re being factual—and we should be—the Dormouse is a bit of a tragic figure in Carroll’s narrative. He is constantly being used as a pillow or pushed into a teapot. During the Trial of the Knave of Hearts, the Dormouse does manage to speak up, but it's mostly to argue with Alice about whether she has a right to grow so fast.

"I wish you wouldn't squeeze so," said the Dormouse, who was sitting next to her. "I can hardly breathe."

Alice tells him she can’t help it, she’s growing.

"You've no right to grow here," said the Dormouse.

That’s a far cry from a psychedelic manifesto. It’s actually a very stuffy, conservative sentiment. The Dormouse represents the sleepy, stagnant part of society that hates change. It’s the ultimate irony that the 60s generation took the name of the most "asleep" character to represent "waking up."

💡 You might also like: Dragon Ball All Series: Why We Are Still Obsessed Forty Years Later

The Counterculture's Obsession with Wonderland

Why Lewis Carroll?

Because Carroll was a mathematician named Charles Dodgson who understood that logic, when pushed to its extreme, looks like insanity. The 1960s were a time when traditional logic—the logic of the Cold War and the Vietnam era—felt deeply insane to the youth.

The "White Rabbit" lyrics aren't just a song; they're a syllabus.

- The pills that make you small? A nod to the restrictive nature of 1950s social norms.

- The mushroom? Obviously a reference to psilocybin, though Carroll likely meant it as a literary device for scale.

- The Red Queen? The arbitrary nature of authority.

When Grace Slick sings about what the dormouse said, she’s actually referencing a specific moment in the book where the Dormouse tells a story that makes no sense. By doing this, she’s telling the listener that "sense" is a construct. If the "sensible" world is the one dropping bombs, then maybe the "nonsense" world of the tea party is actually the safer bet.

Misconceptions That Still Pop Up

You’ll hear people swear that the Dormouse gives Alice advice on which side of the mushroom to eat. He doesn't. That’s the Caterpillar. The Caterpillar is the one sitting on the mushroom, smoking a hookah, being incredibly condescending to a lost little girl.

📖 Related: Down On Me: Why This Janis Joplin Classic Still Hits So Hard

The Dormouse is usually just a bystander.

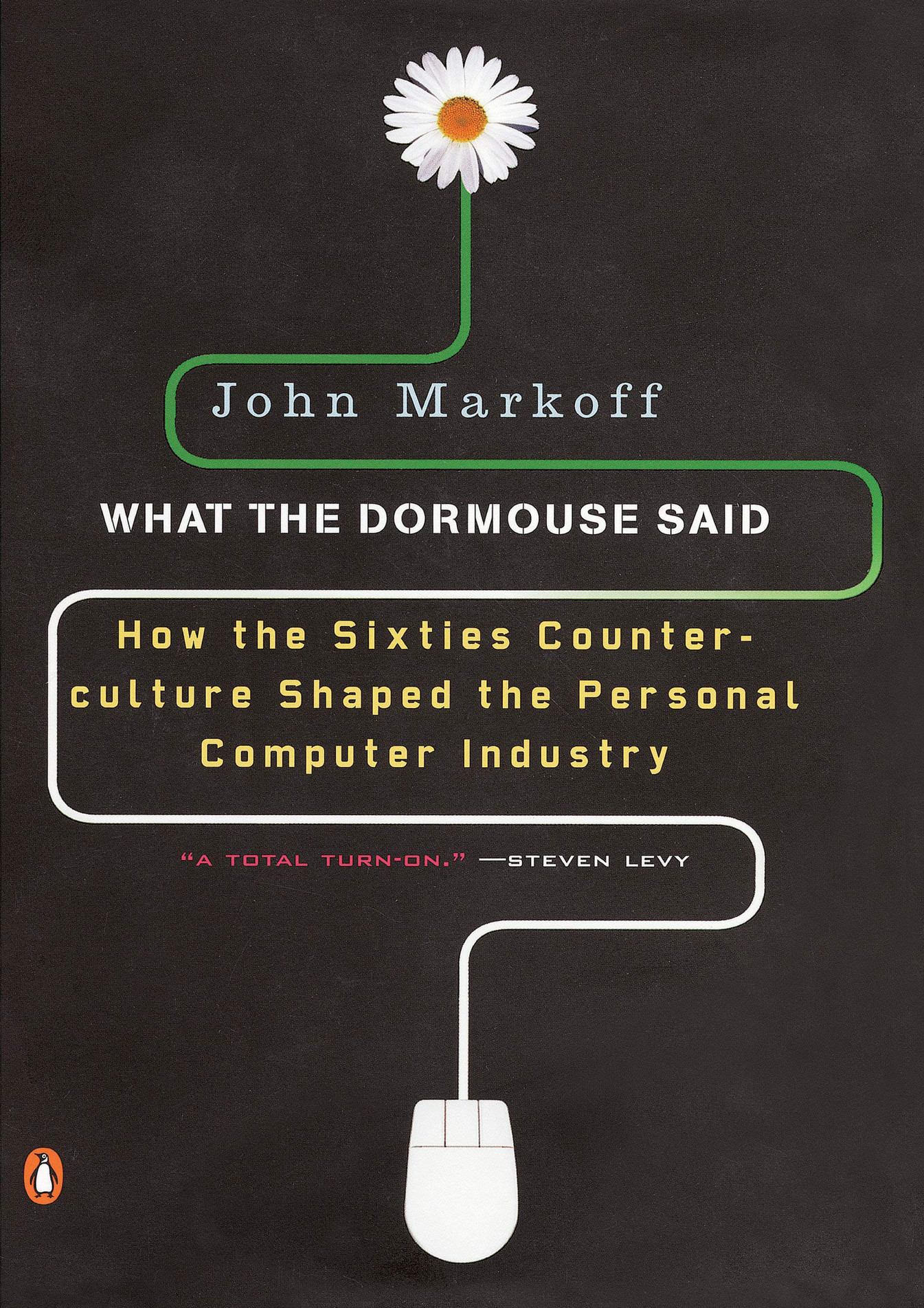

Another weird fact: the "What the Dormouse Said" phrase was so influential it even bled into the tech world. John Markoff wrote a famous book titled What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry. He argues that the guys who designed the first PCs (like those at Xerox PARC and early Apple) were deeply influenced by the "feed your head" philosophy. They saw computers as a way to expand human consciousness, not just calculate spreadsheets.

The Real-World Legacy of the Sleepy Rodent

It’s kinda wild how a minor character in a 19th-century children's book became a pillar of rock and roll and Silicon Valley history. It shows that words don’t really belong to the person who writes them once they hit the public consciousness. They belong to whoever uses them most effectively.

Lewis Carroll’s Dormouse was a sleepy Victorian gag.

Grace Slick’s Dormouse was a prophet of the lysergic revolution.

The tech industry’s Dormouse was a pioneer of the digital age.

When you hear that bassline kick in and those drums start building, you aren't thinking about a mouse in a teapot. You're thinking about the threshold of a new experience. That’s the power of a well-placed literary reference. It takes something old and dusty and makes it feel like it was written five minutes ago in a basement in San Francisco.

How to Actually Use This Information

If you want to sound like you know your stuff next time "White Rabbit" comes on the radio, or if you're writing about the intersection of literature and pop culture, keep these points in mind:

- Separate the Art from the Source: Acknowledge that "Feed your head" is a 1960s addition. It’s not in the book. If you claim it is, someone who actually reads Carroll will call you out.

- Look for the Logic: Carroll was a logic expert. Every "nonsense" thing the Dormouse says is usually a play on words or a linguistic puzzle. For example, the treacle well is likely a reference to "St. Margaret’s Well" in Binsey, which was known as a "treacle" (healing) well.

- Listen to the Delivery: Notice how Slick sings the line. It’s not a suggestion; it’s an ultimatum. That’s the key difference between the Victorian character and the 60s icon.

The next step for anyone interested in this weird overlap is to go read the "A Mad Tea-Party" chapter again. Don't look for drug metaphors. Look for how the characters use language to trap each other. It’s much more "meta" than the songs let on. Then, listen to the isolated vocal track of "White Rabbit." You’ll hear the grit in the performance that turned a sleepy rodent into a household name.