You've been there. You pull a golden-brown drumstick out of the bubbling oil, it looks picture-perfect, but then you bite in and—oops. It’s raw at the bone. Or maybe it’s the opposite: the crust is dark, almost burnt, and the meat inside is basically sawdust. It’s frustrating. Honestly, the biggest mistake home cooks make isn't the seasoning or the flour blend. It's the heat. If you don't know what temp to fry chicken, you're basically gambling with your dinner.

Frying is a violent, high-energy process. You are literally forcing moisture out of the meat while simultaneously trying to polymerize fats and starches on the surface. It's a balancing act. If the oil is too cold, the chicken sits there and drinks grease like a sponge. If it's too hot, the outside chars before the inside even realizes it’s in a pan.

The magic number? It’s $350^{\circ}F$ ($177^{\circ}C$). But here is the thing: that number is a moving target.

The $350^{\circ}F$ Myth and Reality

Most recipes tell you to hit $350^{\circ}F$ and call it a day. That's a decent baseline, but it's also a bit of a lie. Why? Because physics doesn't care about your recipe. The second you drop a cold piece of bird into that hot oil, the temperature is going to plummet.

If you start at $350^{\circ}F$ and throw in four cold thighs, your oil temp might drop to $310^{\circ}F$ or even lower. Now you're simmering chicken in oil. That leads to the dreaded "greasy" chicken. Expert fryers like J. Kenji López-Alt have demonstrated through rigorous testing at Serious Eats that you actually want your oil to stay between $300^{\circ}F$ and $325^{\circ}F$ during the actual cooking process.

To achieve that, you usually need to preheat your oil to about $375^{\circ}F$. This gives you a "thermal buffer." When the chicken goes in, the drop brings you right into the sweet spot.

Why the 325-350 Range Matters

When you're hovering in that $325^{\circ}F$ to $350^{\circ}F$ range, something called the Maillard reaction is working overtime. This is the chemical reaction between amino acids and reducing sugars that gives browned food its distinctive flavor. Below $300^{\circ}F$, this happens too slowly. Above $400^{\circ}F$, you're heading straight toward carbonization.

Think about the moisture. Chicken is mostly water. As it fries, that water turns to steam and escapes. This steam creates a positive pressure barrier that actually prevents the oil from soaking into the meat. If your oil isn't hot enough, there’s not enough steam pressure. The oil wins. The chicken loses. You end up with a heavy, oily mess that makes you feel like you need a nap immediately after eating.

Deep Frying vs. Pan Frying: Does it Change?

It absolutely does. If you’re deep frying—meaning the chicken is totally submerged—you have more leeway because the heat is hitting every single millimeter of the surface area at once.

Pan frying (or shallow frying) is different. Usually, you’re using a cast-iron skillet with maybe an inch of oil. In this scenario, the temperature management is way harder. The bottom of the pan is a direct heat conductor. You have to be more vigilant. For a skillet, I usually aim for a slightly lower starting temp because the recovery time is faster on a heavy piece of iron.

I’ve found that with a cast iron, $335^{\circ}F$ is a safer "working" temperature. It prevents the breading that's touching the bottom of the pan from scorching.

The Type of Oil is the Unsung Hero

You can’t just use any oil. Olive oil? Forget it. Its smoke point is way too low for a sustained fry. You’ll fill your kitchen with acrid blue smoke before the chicken is even halfway done.

You need something with a high smoke point.

- Peanut Oil: The gold standard. It has a smoke point around $450^{\circ}F$ and adds a subtle richness.

- Canola or Vegetable Oil: The budget-friendly workhorses. They’re neutral and have smoke points around $400^{\circ}F$.

- Lard: If you want to go old-school Southern style. It has a lower smoke point (around $370^{\circ}F$), so you have to be incredibly careful not to overheat it, but the flavor is unmatched.

Don't Trust Your Eyes, Trust the Probe

One of the biggest lessons I learned from professional kitchens is that "eyeing it" is for people who like food poisoning or dry meat. You need two tools: an infrared thermometer (or a clip-on candy thermometer) for the oil, and an instant-read meat thermometer for the chicken itself.

The oil needs to stay consistent. But the chicken? That’s the real goal.

✨ Don't miss: The Henry Olson Fuhrman Funeral: Remembering a Life and the Legacy Left Behind

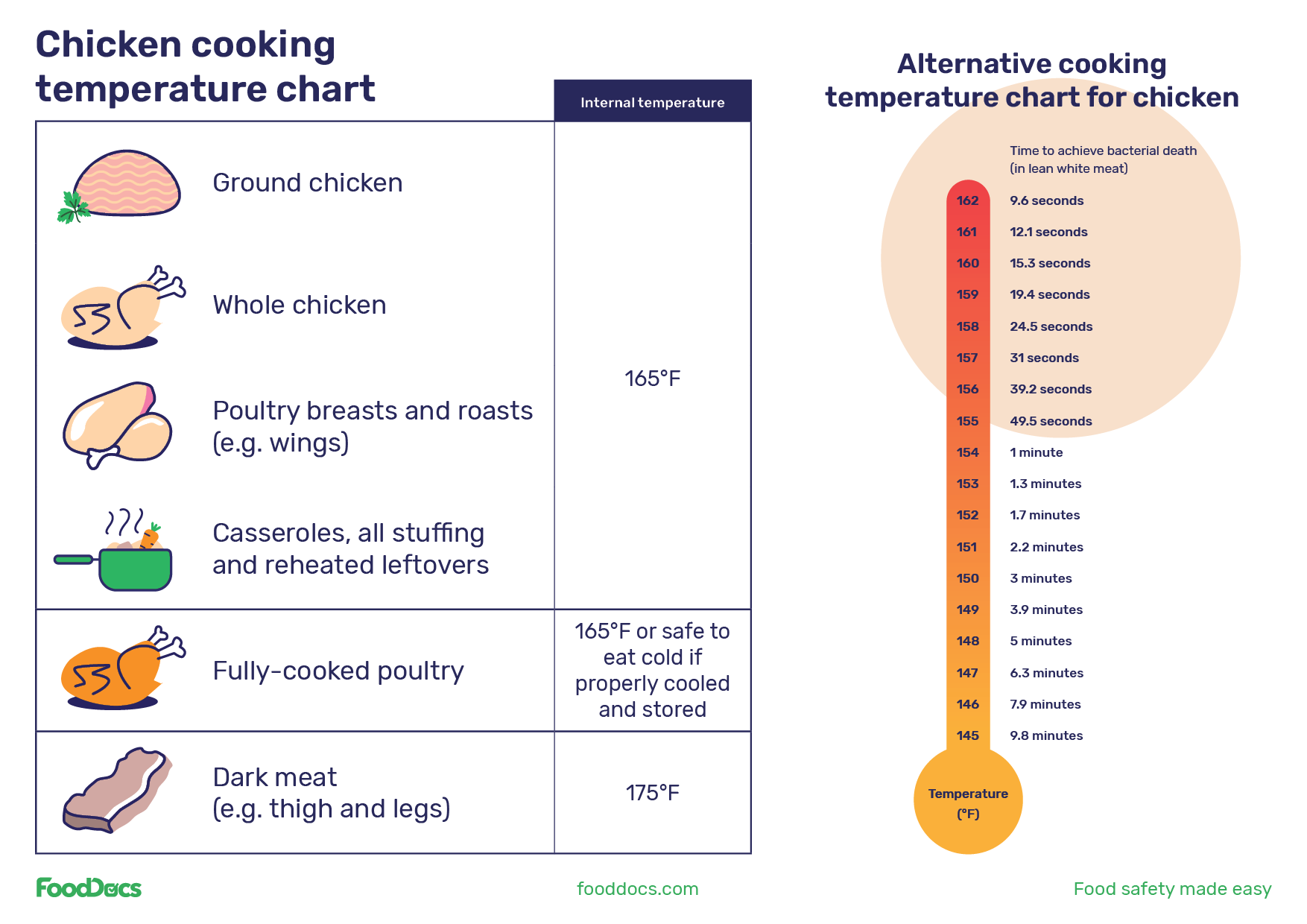

According to the USDA, chicken is safe at $165^{\circ}F$. However, if you're cooking dark meat like thighs or legs, $165^{\circ}F$ is actually kinda gross. It’s often still chewy and has a metallic taste near the bone. Dark meat has more connective tissue (collagen). That collagen doesn't really start to break down into silky gelatin until it hits about $175^{\circ}F$ or $180^{\circ}F$.

White meat—the breast—is the opposite. Hit $165^{\circ}F$ and pull it immediately. If you go to $170^{\circ}F$, you've basically made a desert in your mouth.

The Resting Phase

Here is a detail people often ignore: carryover cooking.

When you pull that chicken out of the $350^{\circ}F$ oil, the surface is much hotter than the center. Once it’s on the cooling rack, that residual heat continues to travel inward. The internal temperature will usually rise another 5 degrees.

I pull my breasts at $160^{\circ}F$ and my thighs at $175^{\circ}F$. Let them rest on a wire rack—not paper towels. Paper towels trap steam, and steam is the enemy of a crispy crust. If you put hot fried chicken on a flat paper towel, the bottom will be soggy within two minutes. Use a wire rack over a baking sheet. Airflow is your best friend.

Common Obstacles and How to Fix Them

"My breading is falling off."

This usually happens because the chicken was too wet when you floured it, or you didn't let the breaded chicken sit for a few minutes before frying. Let it rest for 10 minutes after coating; it helps the flour hydrate and "glue" itself to the skin. Also, don't crowd the pan. If the pieces touch, the steam gets trapped and the breading sloughs off.

👉 See also: The Air Jordan 1 Stealth: Why This Quiet Release Is Actually Getting Better With Age

"The oil is foaming like crazy."

This is usually a sign of two things: either your oil is old and broken down, or you have too much excess flour on the chicken. Shake off the extra. Every bit of loose flour that falls into the oil starts to burn and degrade the quality of your fat.

"The outside is dark but the inside is $140^{\circ}F$."

Your oil is too hot. Period. Turn the flame down. If this happens mid-fry, don't panic. Finish the chicken in a $325^{\circ}F$ oven. It’s a common restaurant trick to get the perfect crust without sacrificing the internal doneness.

Step-by-Step Thermal Mastery

- Dry the bird. Pat it down with paper towels. Moisture on the skin is the enemy of a fast sear.

- Standard Breading Procedure. Flour, then egg wash (or buttermilk), then flour again. This creates those "nooks and crannies" that get extra crispy.

- The Pre-Heat. Get your oil to $375^{\circ}F$. Use a large heavy-bottomed pot to minimize temp swings.

- The Drop. Place the chicken in away from you so you don't get splashed. Don't fill more than half the pot's surface area.

- Monitor. Adjust your burner constantly to keep that oil between $325^{\circ}F$ and $350^{\circ}F$.

- The Check. Use an instant-read thermometer. Aim for $160^{\circ}F$ for breasts and $175^{\circ}F$ for dark meat.

- The Rest. Minimum 5 minutes on a wire rack.

Frying chicken is as much about listening as it is about watching. You’ll notice the "sizzle" changes sound as the chicken gets closer to being done. It goes from a loud, aggressive bubbling (lots of water escaping) to a quieter, more refined hiss. That’s the sound of the moisture levels dropping and the crust setting.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Batch

To get the best results, stop guessing. Buy a digital clip-on thermometer for your pot; it's a $15 investment that changes everything. If you're using a shallow skillet, flip the chicken every 3-4 minutes to ensure even heat distribution, as the side facing the bottom of the pan will always cook faster.

Always salt your chicken immediately after it comes out of the oil. The residual surface oil will help the salt crystals stick. If you wait until it's dry, the salt just bounces off. Lastly, if you're frying in batches, let the oil return to $375^{\circ}F$ before starting the next round. Rushing the process is the fastest way to ruin a good meal.