History isn't usually a single date on a calendar. When people ask when was the Trail of Tears, they’re often looking for a specific year, like 1838. But honestly? It’s way more complicated than just one winter or one march. It was a decade-long grind of legal battles, state-sponsored harassment, and several waves of forced migration that didn't just affect one group of people.

We’re talking about a massive, state-sanctioned relocation of roughly 60,000 Native Americans from the "Five Civilized Tribes"—the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw. It started in the 1830s. It ended, loosely, in 1850. But the trauma? That never really ended.

The Actual Timeline of When Was the Trail of Tears

To understand the timing, you have to look at the Indian Removal Act of 1830. President Andrew Jackson pushed this through, and it basically gave the federal government the "legal" power to trade land in the East for land west of the Mississippi River. Most people think the Cherokee were the only ones involved, but the Choctaw were actually the first to go.

Their "trail" started around 1831. It was brutal.

Imagine being told your home isn't yours anymore because someone found gold or just wanted to plant cotton. That’s what happened in Georgia. The state started holding lotteries to give away Cherokee land while the Cherokee were still living on it. Talk about awkward and terrifying. By 1832, the Seminoles were being pressured in Florida, leading to years of actual warfare. The Creek were forced out in 1834. The Chickasaw followed in 1837.

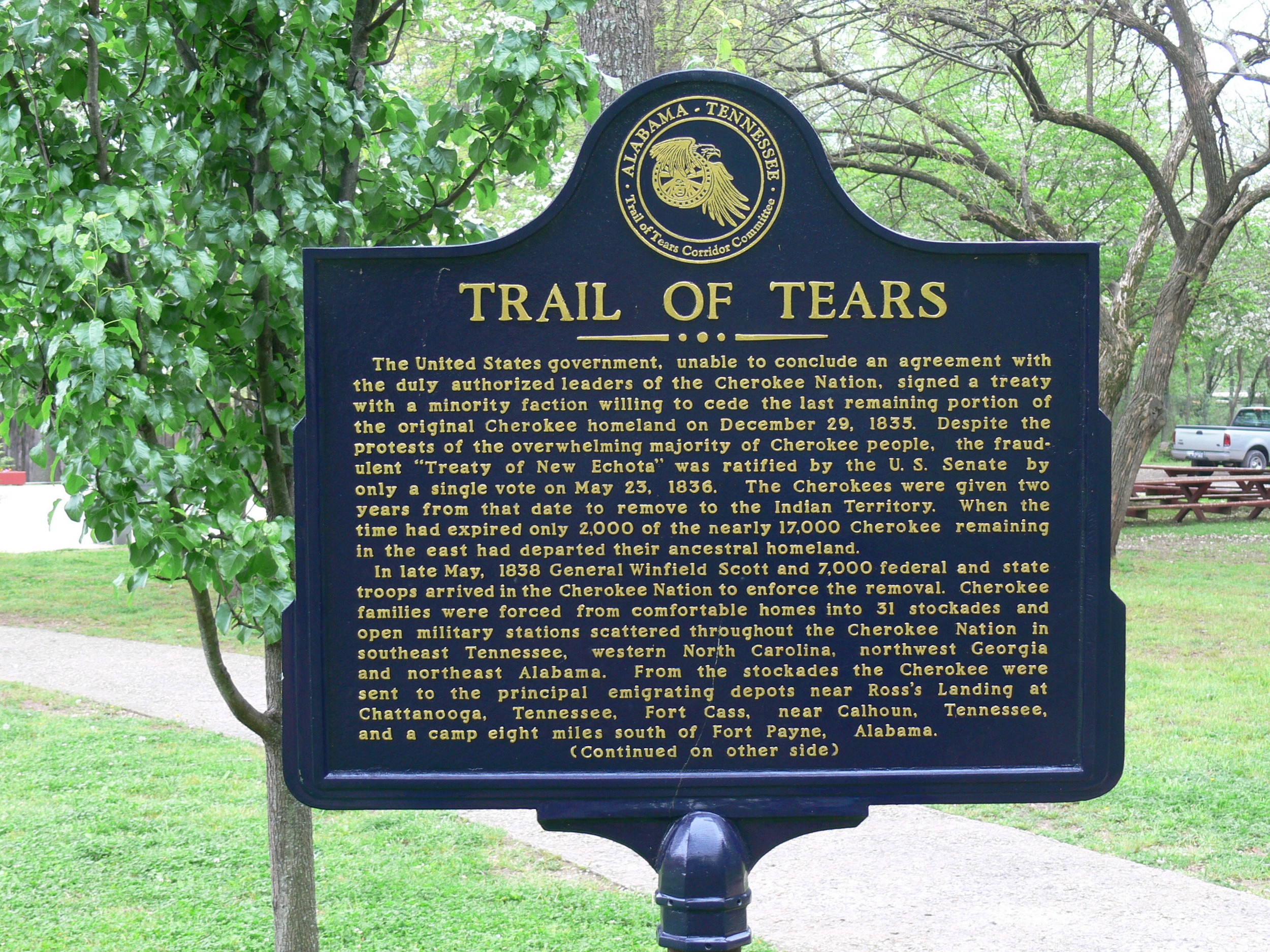

Then came 1838. This is the year most history books focus on because it’s when the "main" Cherokee removal happened under the command of General Winfield Scott. He showed up with 7,000 troops. They rounded people up at bayonet point. People were forced into stockades with nothing but the clothes on their backs.

👉 See also: What Really Happened With the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz

Why the Winter of 1838-1839 is the Most Famous Part

The Cherokee were split into several detachments. Some went by water, which sounds easier but was actually a nightmare of disease and cramped boats. Most went by land.

They walked.

They walked through Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas. The weather was horrific. It was one of the coldest winters on record. One traveler, a man named "Cannon" who led a group, noted in his journals how they had to wait for the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers to thaw just enough to cross, but the ice was still thick enough to crush boats.

It’s estimated that 4,000 Cherokee died. That’s one out of every four people. They died of dysentery, exhaustion, and exposure. If you’ve ever been to the Ozarks in January, you know it’s no joke. Now imagine doing it in thin moccasins or barefoot.

The Legal Battles You Didn't Learn in School

A lot of folks think the Native Americans just took it lying down. They didn't. The Cherokee, specifically, fought this in the Supreme Court. There’s a famous case from 1832 called Worcester v. Georgia. Chief Justice John Marshall actually ruled that Georgia had no right to enforce its laws on Cherokee territory.

✨ Don't miss: How Much Did Trump Add to the National Debt Explained (Simply)

It was a win. On paper.

But Andrew Jackson reportedly said, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it." Jackson just ignored the highest court in the land. It’s one of those "what if" moments in history. If the President had followed the law, when was the Trail of Tears might have been a question we never had to ask because it might not have happened.

Instead, a small, unauthorized group of Cherokee signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835. They weren't the elected leaders. Chief John Ross, who represented the majority, fought the treaty until the very end. He even delivered a petition with over 15,000 signatures to Congress. They ignored him.

The Different Routes Taken

Not everyone took the same path to what is now Oklahoma.

- The Northern Route: This is the famous one through Missouri and Illinois. It was used by the largest groups.

- The Water Route: Utilizing the Tennessee, Ohio, and Mississippi Rivers.

- The Bell Route: A specific path taken by a smaller group of 660 people.

- The Benge Route: A 700-mile trek starting in Alabama.

The variety of paths meant that the suffering was spread across half the country. People in small towns in Illinois watched thousands of starving, freezing people walk past their front doors. Some locals tried to help; others charged them triple price for food and supplies. It was a mess of human nature—the best and the worst of it.

🔗 Read more: The Galveston Hurricane 1900 Orphanage Story Is More Tragic Than You Realized

The Long-Term Impact on Oklahoma

When they finally arrived in "Indian Territory," it wasn't a land of milk and honey. It was unfamiliar territory where they had to start from zero. The Chickasaw, who were arguably the best prepared financially, still struggled with the psychological toll. The Creek arrived to find their designated lands were already being encroached upon.

By 1850, the initial "removal" phase was largely over, but the fallout lasted decades. The tribes had to rewrite their constitutions, build new capitals (like Tahlequah for the Cherokee), and try to heal from the fact that they’d lost an entire generation of elders and children on the road.

Honestly, the sheer scale of the logistical failure—or perhaps the intentional cruelty—is hard to wrap your head around. The government knew they didn't have enough blankets. They knew the food was spoiled. They did it anyway.

Essential Facts to Remember

- Total Distance: Many groups walked over 1,000 miles.

- Death Toll: Estimates vary, but 10,000+ across all tribes is a conservative guess.

- The Term: The phrase "Trail of Tears" actually comes from a Cherokee phrase Nunna daul Isunyi—"The Trail Where They Cried."

- Modern Day: Today, the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail covers over 5,000 miles of land and water routes across nine states.

Where to Go From Here

If you really want to understand the gravity of when was the Trail of Tears, you shouldn't just read about it. You need to see the maps and the primary documents.

- Visit the National Historic Trail sites: There are markers in places like Port Royal State Park in Tennessee or the Trail of Tears State Park in Missouri. Standing on the ground where it happened changes your perspective.

- Read Chief John Ross’s letters: You can find these in many university archives or online through the Library of Congress. Seeing his desperate pleas to the U.S. government makes the history feel much more "real" and less like a textbook entry.

- Support Native-led historical preservation: The Cherokee Nation and other tribes have their own museums and historical societies. They are the best sources for the nuances of their own history.

- Check out the "Database of Indigenous Slavery": Often overlooked, the Trail of Tears also involved enslaved African Americans who were owned by members of the tribes. Understanding the intersectionality of that era is key to a full historical picture.

History isn't just about dates. It's about the people who lived through the "when." The 1830s were a period of massive expansion for some and total devastation for others. Recognizing that duality is the first step toward actually learning from it.

Next Steps for Research:

Start by looking up the Treaty of New Echota text. It's the document that legally "justified" the Cherokee removal despite being signed by a minority group. From there, trace the route of the Choctaw in 1831 to see how the pattern was established long before 1838. If you're near the Southeast, visit the New Echota State Historic Site in Georgia to see where the Cherokee capital stood before everything changed.

The story of the Trail of Tears isn't just a "Native American story"—it's an American story that shaped the borders, the economy, and the moral landscape of the entire country. Understanding the timeline is just the beginning of understanding the cost of that growth.