It wasn't just about the soup lines. When people ask what was unemployment in the great depression, they usually expect a single number, like 25%. But that number is a sanitized version of a much messier, more terrifying reality. It wasn't just a "bad job market." It was the total collapse of the American idea that if you worked hard, you could eat.

The ground basically fell out from under everyone.

Honestly, we talk about the 1929 stock market crash like it was the start of the unemployment crisis, but that’s not quite right. The crash was the spark, but the fire took years to grow. By 1933, things were so bleak that nearly 13 million people were out of work. In some cities, the situation was even weirder and worse than the national average. If you lived in Toledo, Ohio, in 1932, your chances of being unemployed weren't one in four—they were eight in ten. 80% unemployment. Imagine that. You walk down a street and almost nobody has a job.

The Number Nobody Can Agree On

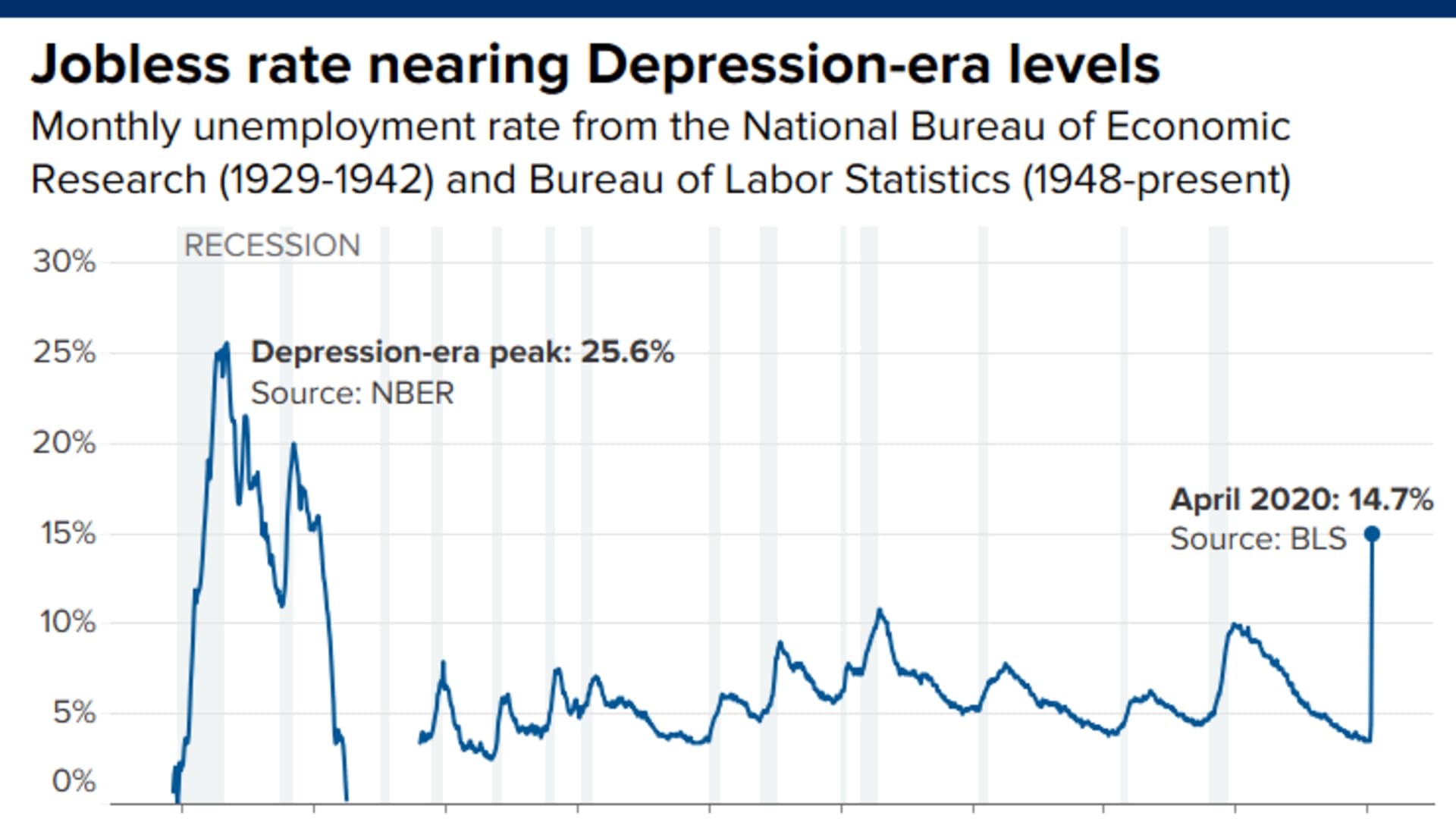

Economists today still argue about the exact statistics because, frankly, the government wasn't great at keeping track back then. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) didn't have the sophisticated monthly surveys we use now. Most historians, like David Kennedy in his Pulitzer-winning Freedom from Fear, point to the 24.9% peak in 1933 as the gold standard for what was unemployment in the great depression.

But even that 25% figure is sort of misleading.

It doesn't account for "underemployment." Millions of people were technically "employed" but were only working three hours a week for pennies. Or they were farmers who were working 14-hour days but losing money on every bushel of wheat they grew because prices had cratered. If you factor in those people—the ones whose jobs didn't actually provide a living—some experts suggest the "real" struggle affected closer to 50% of the population.

📖 Related: Saudi Dinar to INR: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the Jobs Just Vanished

The cycle was vicious. It's called a deflationary spiral. Businesses saw demand drop, so they laid off workers. Because those workers now had zero income, they stopped buying stuff. Because they stopped buying stuff, more businesses went bust.

It was a domino effect that nobody knew how to stop.

The manufacturing sector took the hardest hit. If you were making "durable goods"—cars, refrigerators, furniture—you were toast. People can skip buying a new Ford, but they can't skip eating. Consequently, heavy industry employment plummeted. Between 1929 and 1932, the payrolls at United States Steel dropped from 225,000 full-time workers to literally zero. They kept people on part-time just to maintain the equipment, but the actual production jobs evaporated.

The Myth of the "Lazy" Unemployed

There's this weird misconception that people just sat around waiting for handouts. That couldn't be further from the truth. Men—and it was mostly men considered in the "official" stats back then—would walk miles just on a rumor of a job.

You've probably seen the photos of "Hoovervilles." These were shanty towns made of cardboard and scrap metal. They weren't just for "hobos." They were filled with former bank tellers, architects, and skilled mechanics. People sold apples on street corners for five cents not because it was a good business, but because it was the only thing left to do.

The psychological toll was massive. Sociologists at the time, like E. Wight Bakke, studied unemployed men and found a consistent pattern: first came anxiety, then a frantic search for work, then a deep, soul-crushing shame. Society told these men they were providers. When they couldn't provide, they felt like they didn't exist.

The Relief Effort That Wasn't

For the first few years, the government basically did nothing. President Herbert Hoover believed in "rugged individualism." He thought private charity should handle it.

The problem?

Charity ran out of money in about five minutes. New York City's relief fund was exhausted by 1931. In Chicago, teachers weren't paid for months, yet they kept showing up because they knew their students were starving. By the time Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in 1933, the nation was at a breaking point.

Roosevelt's "New Deal" changed the definition of what was unemployment in the great depression by introducing "work relief." Instead of just giving people a check (which many thought was degrading), the government created jobs.

🔗 Read more: Can Employers Still Require COVID Vaccines 2024: The Real Story

- The CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps): Put young men to work planting billions of trees and building state parks.

- The WPA (Works Progress Administration): This was the big one. It hired everyone from construction workers to actors and historians.

Wait, historians? Yeah. The government paid people to interview former slaves and write local guidebooks. It was a recognition that "unemployment" applied to the mind as well as the muscles.

Regional Disasters and the Dust Bowl

It's impossible to talk about the job market without mentioning the weather. While the banks were failing in the East, the dirt was flying in the Midwest. The Dust Bowl created a class of "migrant" unemployed.

These weren't people looking for a career change; they were refugees in their own country.

When the crops died and the banks foreclosed on the farms, hundreds of thousands of "Okies" packed their lives into jalopies and headed to California. But California didn't want them. Local police sometimes set up "bum blockades" at the state border to turn back anyone who didn't have money. This was the most desperate face of unemployment—being homeless and unwanted in a land that was supposed to be yours.

Women and Minorities: The Forgotten Stats

If you were Black or a woman during the Depression, the official unemployment numbers didn't even begin to cover your struggle.

The rule for Black workers was "last hired, first fired." In many Northern cities, the unemployment rate for African Americans was double or triple that of white workers. In the South, Black sharecroppers were often kicked off their land so the owners could claim government subsidies meant for "not planting" crops.

For women, there was actually a push to ban them from working. People argued that women were "stealing" jobs from men who needed to support families. Some states even passed laws making it illegal for a husband and wife to both work for the government. Despite this, women's employment actually stayed more stable in some sectors—like nursing and teaching—because those "pink collar" jobs didn't collapse as hard as steel or coal.

When Did It Actually End?

People think the New Deal fixed everything. It didn't.

💡 You might also like: What Is the Dow Jones Average Today: Why the Market is Acting So Weird

While the New Deal kept people from starving, it didn't solve the unemployment problem entirely. In 1937, there was a "recession within the depression," and unemployment spiked back up to 19%. It took a literal world war to end the crisis.

When the U.S. started building planes, tanks, and ships for World War II, the labor surplus vanished overnight. By 1944, unemployment was down to 1.2%. We went from having too many workers to not enough.

Lessons for Today

Looking back at what was unemployment in the great depression offers more than just a history lesson. It shows us the fragility of the "system."

If you want to apply these historical insights to your own financial resilience, consider these moves:

- Diversify Skills, Not Just Investments: The people who survived best were those who could pivot. In the 1930s, a mechanic who could also fix a radio survived better than a specialist. Today, that means having a "side stack" of skills outside your primary industry.

- Emergency Funds are Non-Negotiable: During the Depression, people lost their life savings when banks folded. While we have FDIC insurance now, the "cash is king" rule still applies during market contractions. Aim for six months of actual living expenses.

- Watch the "Underemployment" Metric: Don't just look at the headline unemployment rate in the news. Look at the U-6 rate, which includes people who have given up looking or are working part-time involuntarily. It’s a much more accurate pulse of the economy’s health.

- Understand the Deflationary Risk: Most of us fear inflation, but the Depression was a lesson in the horror of deflation. When prices drop, debt becomes "heavier" because the dollars you owe are worth more than the dollars you earn. Keeping your debt-to-income ratio low is the best defense against this kind of structural collapse.

The Great Depression changed the DNA of the world. It’s the reason we have Social Security, the reason we have a minimum wage, and the reason we have unemployment insurance. It was a painful way to learn that in a modern economy, we are all connected. When your neighbor loses their job, eventually, it becomes your problem too.