Deep under the blackland prairie of Waxahachie, Texas, there is a ghost. It isn’t a person, but a series of hollowed-out tunnels—billions of dollars’ worth of ambition left to fill with groundwater. If you drive about 30 miles south of Dallas, you’re standing over what was supposed to be the "Cathedral of Physics." Instead, the Superconducting Super Collider Texas project became one of the most expensive "what ifs" in American scientific history.

It was going to be massive. Truly gargantuan. We’re talking about a ring 54 miles in circumference. To put that in perspective, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Switzerland—the one that actually found the Higgs Boson—is only about 17 miles around. The Texas machine would have been three times larger and significantly more powerful. Scientists weren't just looking for the "God Particle"; they were looking for the very blueprints of the universe.

Then, in 1993, Congress pulled the plug.

People still argue about why. Was it the soaring costs? Bad management? Or did the end of the Cold War simply kill the appetite for "Big Science"? Honestly, it was a messy mix of all three, seasoned with a healthy dose of Texas-sized political maneuvering that eventually backfired.

The Massive Ambition of the Superconducting Super Collider Texas

In the late 1980s, American physicists were worried. Europe was gaining ground in high-energy physics, and the U.S. wanted to leapfrog everyone. The plan for the Superconducting Super Collider Texas (SSC) was birthed from that desire to stay dominant. It wasn't just about pride, though. The SSC was designed to collide protons at energies of 40 tera-electronvolts (TeV). For context, the LHC currently operates at around 13.6 TeV.

We are talking about a machine that could have unlocked physics we still don't understand today. Dark matter. Extra dimensions. The fundamental reasons why matter has mass.

The site selection was a whole drama in itself. Dozens of states applied, basically begging for the thousands of high-tech jobs and prestige the project would bring. Texas won. Waxahachie had the perfect geology—a thick layer of Taylor Marl chalk that was easy to tunnel through but stable enough to hold the massive magnets required to steer subatomic particles at nearly the speed of light.

Why Waxahachie?

It wasn't just the dirt. It was the politics. Vice President George H.W. Bush was a Texan. The Speaker of the House, Jim Wright, was a Texan. The political stars aligned, and by 1991, construction was in full swing. They actually finished about 14.7 miles of tunnel. They built massive surface facilities. They even started hiring the world’s brightest minds, moving families from around the globe to a small town known for its gingerbread houses and annual Renaissance fair.

👉 See also: The Problem With Colorized Black and White Photos (and Why We Can't Stop Looking)

Where the Money Went and Why It Stopped

By 1993, the budget had spiraled. What started as a $4.4 billion estimate had ballooned to over $11 billion. In the halls of Congress, this didn't sit well. You had the International Space Station (ISS) also competing for massive amounts of funding, and many politicians felt the U.S. couldn't afford two "megaprojects."

It’s often said that the Superconducting Super Collider Texas was killed by a "death by a thousand cuts."

- The Budget Deficit: The early 90s saw a massive push for fiscal responsibility. The "deficit hawks" in the House of Representatives needed a trophy to show they were serious about cutting spending.

- Management Failures: An audit by the Department of Energy (DOE) found some pretty cringey spending. We’re talking about thousands of dollars spent on "official" potted plants and high-end office furniture while the project was already over budget. These details were absolute gold for critics like Representative Roemer of Indiana, who led the charge to kill the SSC.

- The Cold War Factor: Once the Soviet Union collapsed, the "prestige" of winning the science race felt less urgent to the average voter.

When the House finally voted to cancel the project in October 1993, it was a gut punch to the scientific community. Over 2,000 people lost their jobs almost overnight. Physicist Leon Lederman, who had coined the term "The God Particle," was devastated. He and others argued that the U.S. was ceding its leadership in fundamental science—a prediction that arguably came true when the LHC stole the spotlight a decade later.

Life After Death: What's Left in Waxahachie?

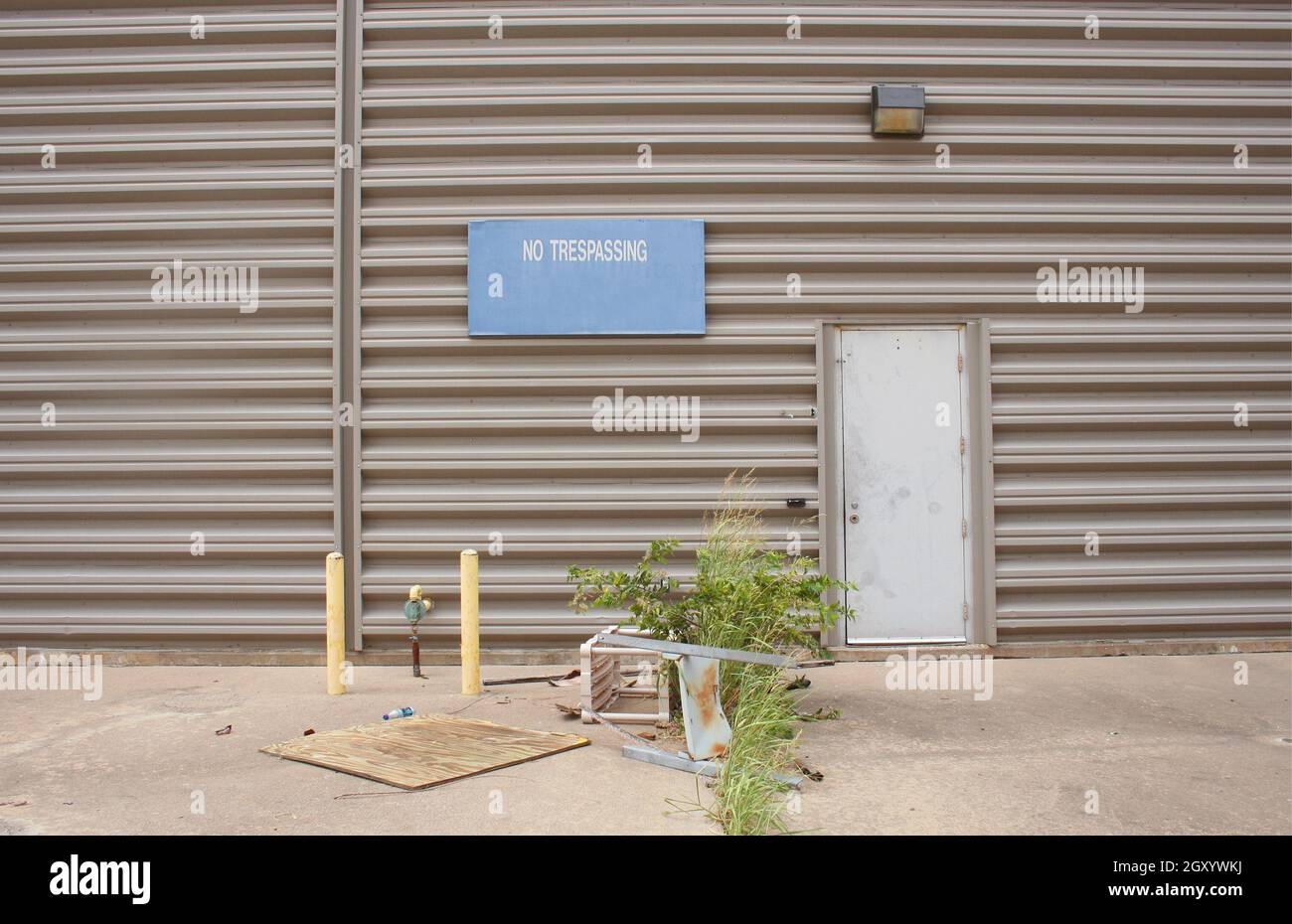

If you visit the site today, it’s a bit eerie. For years, the massive gray buildings sat empty, guarded by a skeleton crew. It looked like a Bond villain's lair that had gone bankrupt.

Eventually, a chemical company bought the main site. They use the massive, reinforced buildings for manufacturing and storage. But the tunnels? They’re still there, hundreds of feet below the surface. They’ve been capped and allowed to fill with water to prevent collapse. It’s a literal time capsule.

Some people think the Superconducting Super Collider Texas was a total waste. I'm not so sure. Even though the ring was never finished, the research conducted during the design phase led to massive leaps in superconducting magnet technology. These are the same kinds of magnets used in MRI machines and modern maglev trains. We got the "tech leftovers," even if we didn't get the main course.

The Human Cost of Scientific Failure

It’s easy to talk about billions of dollars, but the human stories are what stick. Scientists had moved their entire lives to North Texas. Children were enrolled in local schools. When the project died, the "Brain Drain" was real. Many of those physicists ended up leaving the country or moving into finance—using their math skills to predict stock market swings instead of the secrets of the Big Bang. That’s a loss you can’t really put a price tag on.

Was the SSC Really Better than the LHC?

This is a hot topic in physics circles. Technically, yes. The SSC was designed to be much more powerful. If it had been completed, we might have discovered the Higgs Boson in the late 90s instead of 2012. More importantly, we might have found what lies beyond the Higgs.

Right now, the physics world is in a bit of a "crisis." The Standard Model is complete, but it doesn't explain everything. We need higher energies to see the next layer of reality. The Superconducting Super Collider Texas would have provided those energies decades ago. Instead, the global physics community is now talking about building a "Future Circular Collider" (FCC) that would be 100 kilometers long.

It feels like we’re just trying to build what Texas almost had forty years ago.

Moving Forward: Lessons from the Texas Tunnels

We shouldn't just look at the SSC as a failure. It’s a case study in how not to manage a megaproject, sure, but it’s also a reminder of what happens when a nation loses its appetite for the unknown.

If you're interested in the history of science or just like looking at abandoned megastructures, the story of the Superconducting Super Collider Texas is worth your time. It’s a reminder that progress isn't a straight line. Sometimes it’s a circle that never quite closes.

Actionable Insights for Science Enthusiasts

If you want to dive deeper into this or see the impact of Big Science today, here is what you can actually do:

- Visit the Site (Virtually): You can't exactly go touring the tunnels—they're flooded and on private property—but use satellite imagery (search for "SSC site Waxahachie") to see the footprint of the facilities that still exist.

- Read "The God Particle": Leon Lederman’s book gives the best insight into what the scientists hoped to achieve before the funding was cut.

- Support Current Research: Follow the updates from CERN and the proposed Electron-Ion Collider (EIC) at Brookhaven National Laboratory. These are the spiritual successors to the SSC's mission.

- Engage with Local History: If you're ever in Ellis County, Texas, visit the local museums. They often have small exhibits or archives about the years when the world’s smartest people descended on their small town.

The tunnels might be full of water, but the questions they were meant to answer are still very much alive. We are still searching for the same truths; we’re just doing it a little further east these days.