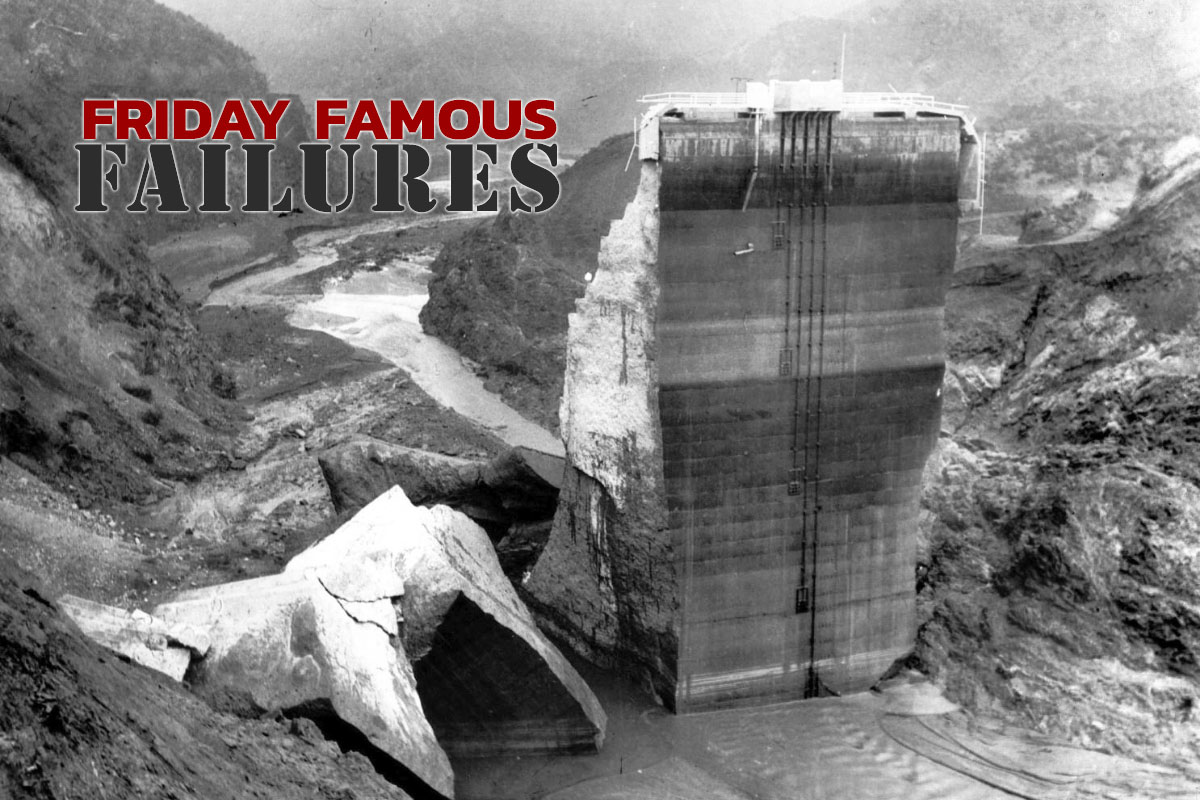

The concrete was still curing when the wall gave way. It wasn't a slow leak or a manageable crack. At nearly midnight on March 12, 1928, a 200-foot-high wall of water obliterated the San Francisquito Canyon. It didn't just flood; it erased everything in its path. We’re talking about the St. Francis Dam disaster, a catastrophe that remains the second-deadliest disaster in California history, surpassed only by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.

William Mulholland was the man behind it. He was a self-taught engineering titan, the guy who basically built Los Angeles by bringing water from the Owens Valley. People worshipped him. But by 12:05 AM on March 13, his legacy was mud. Literally. A 140-foot wall of water surged down the canyon, carrying chunks of concrete the size of houses. It traveled 54 miles to the Pacific Ocean, picking up mud, trees, cattle, and people. It was a nightmare that lasted over five hours and killed at least 431 people, though the real number is likely higher because of the many migrant workers whose names weren't on official registries.

The Fatal Flaw in the San Francisquito Canyon

Why did it fall? Most people think it was just bad luck or a weird earthquake. Honestly, it was hubris. Mulholland and his assistant, Harvey Van Norman, inspected the dam just hours before it collapsed. They saw muddy water seeping from the relief pipes. To them, it looked like standard "sloughing"—just a bit of dirt from a new road. They were wrong. It was actually the foundation of the dam dissolving.

The geology of the site was a mess. The eastern side of the dam was built on Pelona Schist, a rock that likes to slide. The western side sat on Sespe conglomerate. If you put that conglomerate in a jar of water and shake it, it turns into mush. Mulholland didn't know that. Or maybe he didn't want to know. He was under immense pressure to store water for a growing, thirsty Los Angeles.

👉 See also: Who's the Next Pope: Why Most Predictions Are Basically Guesswork

A Chain Reaction of Failure

When the dam failed, it didn't just crumble from the middle. The western abutment gave way first. Imagine a giant door swinging open. As the water surged through, it undercut the center section. Then the eastern side, sitting on that slippery schist, just slid away. Within minutes, 12 billion gallons of water—enough to fill about 18,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools—was screaming toward the Santa Clara River Valley.

Power plant No. 2, located just a few miles downstream, was vaporized. The workers living there didn't stand a chance. Some bodies were found miles away, buried under layers of silt so thick that search teams had to use long steel rods to find them. The "motorcycle Paul Revere," an officer named Thornton Edwards, raced ahead of the flood on his bike to warn the residents of Santa Paula. He saved hundreds, but he couldn't save everyone.

Why the St. Francis Dam Disaster Changed Engineering Forever

Before 1928, dam building in California was a bit like the Wild West. You had an idea, you had the money, and you built it. There was no mandatory state oversight for municipal projects. After the St. Francis Dam disaster, the state realized that leaving the lives of thousands of people in the hands of one man—no matter how legendary—was a recipe for slaughter.

✨ Don't miss: Recent Obituaries in Charlottesville VA: What Most People Get Wrong

This event led directly to the creation of the California Division of Safety of Dams. It basically ended the era of the "all-powerful" chief engineer. It’s the reason why, today, every major dam project undergoes rigorous peer reviews and geological surveys that would have made Mulholland’s head spin.

The Aftermath and the Ghost of William Mulholland

Mulholland took the blame. All of it. At the coroner's inquest, he famously said, "I envy the dead." He was a broken man. He resigned shortly after and lived out his final years in a sort of self-imposed exile. The city of Los Angeles ended up paying out millions in settlements, which was unprecedented at the time. They didn't even fight the lawsuits; they knew they were liable.

Even now, if you hike out to the site in the San Francisquito Canyon, you can see the ruins. There’s a massive chunk of concrete nicknamed "The Tombstone" that stood for years before the city finally blasted it down because it was a morbid tourist attraction. The scars on the canyon walls are still there. You can see exactly how high the water reached by looking at the "scour line" where the vegetation still grows differently.

🔗 Read more: Trump New Gun Laws: What Most People Get Wrong

Modern Lessons from a 1920s Tragedy

You might think a disaster from nearly a century ago doesn't matter much in 2026. But look at the Oroville Dam crisis a few years back. The same themes keep popping up: aging infrastructure, geological surprises, and a bit of overconfidence in our ability to control nature.

The St. Francis Dam teaches us that water always finds the weakness. Whether it’s a hairline crack or a misunderstood rock formation, gravity doesn't care about your reputation or your budget.

What you can do to stay informed about dam safety:

- Check the National Inventory of Dams (NID): This is a public database maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. You can look up dams in your area and see their "hazard potential" rating.

- Understand Inundation Maps: If you live near a dam, your local office of emergency services has maps showing where the water would go if the dam failed. Know your evacuation route.

- Support Infrastructure Funding: These structures aren't "set it and forget it." They require constant maintenance and retrofitting as our understanding of geology and seismic activity evolves.

The story of the St. Francis Dam isn't just a history lesson; it's a warning. It reminds us that when we build big, we have to be humble enough to listen to the earth beneath our feet. We can't afford another midnight in the canyon.