The dirt flew in October. On a crisp day in 1792, a group of freemasons, laborers, and commissioners gathered in a muddy patch of Maryland—which we now call Washington, D.C.—to lay a cornerstone that would basically disappear for two centuries. They weren't just building a house. They were trying to prove that a brand-new democracy could actually hold its own against the palaces of Europe. But honestly, the original white house 1792 version was a mess of compromises, ego trips, and back-breaking labor that most history books gloss over.

It wasn't always called the White House. Back then, it was the "President’s Palace" or the "President’s House." George Washington, who had a very specific, almost obsessive vision for the Federal City, didn't want a cramped villa. He wanted something grand. Yet, he never actually lived in it. By the time the roof was on and the fires were lit, John Adams was the one moving into a damp, smelling-of-wet-plaster building that was still very much a construction site.

The Contest That Started It All

In 1792, Thomas Jefferson—acting as Secretary of State—suggested a design competition. It was a very "Enlightenment" thing to do. They put an ad in the newspapers offering a gold medal worth $500 to whoever could dream up the best house for the leader of the free world. It was an open call. Professional architects, amateurs, and even Jefferson himself (under a pseudonym) submitted drawings.

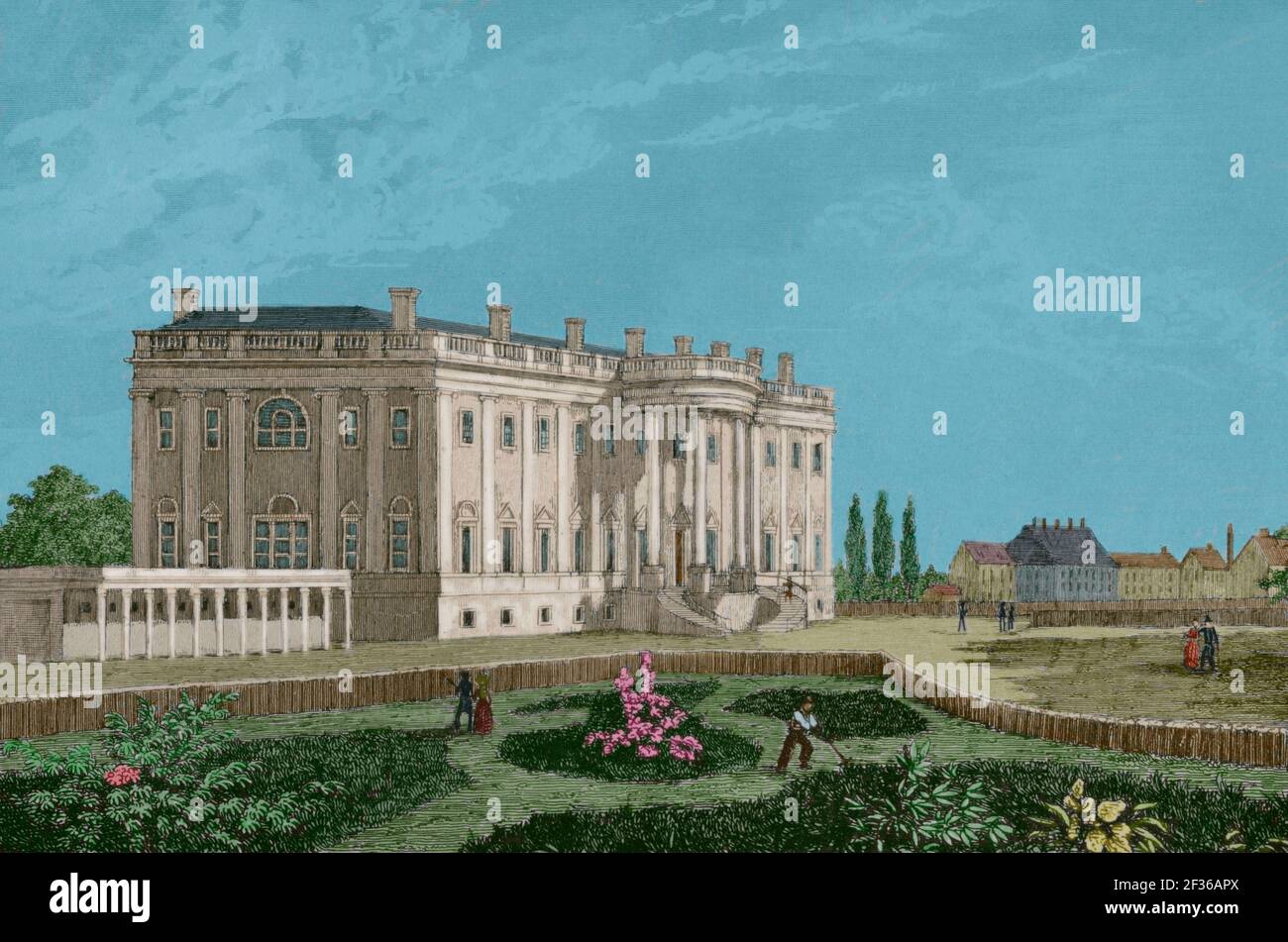

James Hoban won. He was an Irish-born architect who had recently finished the South Carolina Statehouse. His plan for the original white house 1792 was inspired by Leinster House in Dublin. If you look at photos of Leinster House today, the resemblance is uncanny. It’s basically the same building, just minus a few American flourishes. Washington liked Hoban’s plan because it was big, bold, and looked "presidential" in a way the other entries didn't. Some of the other submissions were honestly pretty weird—clunky, oddly proportioned, or way too small for what Washington had in mind.

The Labor No One Talks About

Let's get real for a second. You can't talk about the construction of the original white house 1792 without talking about who actually moved the stones. The site was a swampy, wooded mess. To clear the land and quarry the Aquia Creek sandstone, the commissioners hired both European immigrants and enslaved African Americans.

💡 You might also like: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

Records from the era show that enslaved people were involved in every single step. They were the ones in the pits at Aquia Creek, Virginia, cutting the massive blocks of stone. They were the ones hauling them up the Potomac on flatboats. They worked alongside Scottish stonemasons who were brought over specifically for their skill with a chisel. It was a bizarre, uncomfortable mix of free and forced labor that built the literal symbol of American liberty. The government actually rented enslaved people from local owners, paying the owners the wages while the workers did the grueling labor in the humidity of the D.C. summers.

Why the Sandstone was Painted White

There’s a persistent myth that the White House was painted white to hide burn marks after the British torched it in 1814. That’s just not true.

The original white house 1792 design called for Aquia Creek sandstone, which is a porous, somewhat greyish-tan stone. It looks okay, but it’s a nightmare in the rain. It soaks up water like a sponge. To protect the stone from freezing and cracking, the builders applied a lime-based whitewash in 1798. It wasn't about aesthetics at first; it was about basic maintenance. The white color stuck, and people started calling it the "White House" long before it became the official name in 1901 under Teddy Roosevelt.

It Was Much Bigger Than People Realized

Washington actually intervened to make the house bigger. He saw Hoban's original winning sketch and basically said, "Make it 20 percent larger." He wanted it to be three stories tall, though they eventually settled on two main floors over a high basement to save on costs and time.

📖 Related: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

The scale of the project was insane for the time. It was the largest house in America until after the Civil War. Imagine standing in a city that barely had paved roads, looking at this massive, gleaming white stone structure rising out of the woods. It must have looked like an alien spacecraft had landed in the middle of a forest.

What’s Left of the 1792 Version?

Not much. That’s the short answer.

The British did a real number on the place in 1814. They piled up the furniture, threw in some oil, and lit it up. The fire was so hot that it cracked the stone walls. When James Hoban came back to rebuild it, he had to replace a lot of the original 1792 masonry. Then, in the late 1940s, Harry Truman realized the whole building was literally falling down. The floors were sagging, and a piano leg even poked through a ceiling.

Truman had the entire interior gutted. They took everything out until it was just a hollow shell of stone walls supported by steel beams. So, while the "bones" of the original white house 1792 exterior walls are still there, the inside is a completely different building from what Adams or Jefferson walked through.

👉 See also: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

The Mystery of the Cornerstone

Remember that cornerstone from October 1792? Nobody knows where it is.

Serious historians and amateur treasure hunters have been looking for it for decades. It’s supposed to have a brass plate commemorating the event. During the Truman renovation, they used metal detectors and X-rays to try and find it. Nothing. Some think it was stolen. Others think it’s buried under a later addition or that the brass plate was removed by souvenir hunters in the 1800s. It remains one of the greatest architectural mysteries in D.C. history.

How to See the History Today

If you want to actually "feel" the 1792 era, you can't just look at the North Portico. You have to look at the details.

- Visit the White House Historical Association: They have the best records on the 1792 construction and Hoban's original sketches.

- Go to Aquia Creek: You can still see the remains of the quarries where the original stone was pulled.

- Check the Masonry: If you get close enough to the exterior (which is hard these days with security), you can see some of the original tool marks from the 1790s stonemasons on the older sections of the wall.

The original white house 1792 wasn't a perfect monument. It was a chaotic, expensive, and deeply flawed project that mirrored the country it was built for. It was a house built by people who didn't know if the government would even exist in twenty years. That’s what makes it fascinating—not the fancy dinners or the famous speeches, but the grit, the mud, and the sandstone that started it all.

To truly understand the site, start by researching the James Hoban original elevations at the Library of Congress. These documents show the transition from the Dublin-inspired "Palace" to the scaled-down executive mansion we recognize. Next, look into the payroll records of the 1790s commissioners; these documents provide the most honest account of the diverse, and often exploited, workforce that actually laid the foundations. Understanding the physical struggle of 1792 changes how you see the building today. It stops being a postcard and starts being a real, breathing piece of engineering.