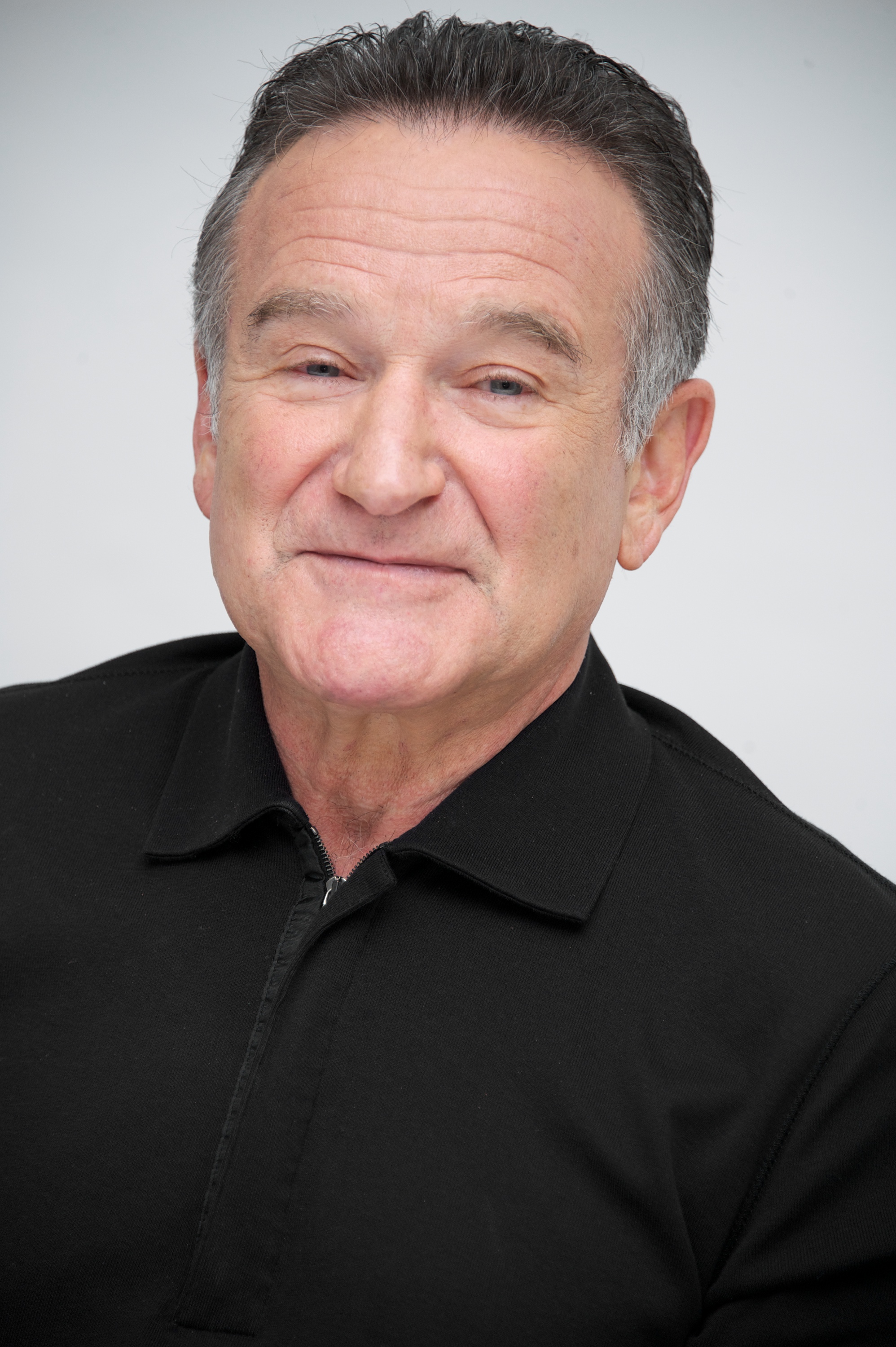

The world basically stopped on August 11, 2014. We all remember where we were when the news broke that Robin Williams—the man who felt like everyone's favorite uncle, the genie in the lamp, the lightning-bolt of manic joy—had died by suicide. For a long time, the narrative was simple, if heartbreaking: he was a sad clown. People assumed he’d finally lost a lifelong battle with depression.

But that wasn't the whole story. Not even close.

It wasn't until the autopsy results came back three months later that we learned the truth. Robin Williams didn't just have a "heavy heart." He had a brain that was, quite literally, under siege. The coroner found "diffuse Lewy body disease," better known as Lewy Body Dementia (LBD).

The "Terrorist" Inside His Brain

Susan Schneider Williams, Robin’s widow, later described the disease as a "terrorist" inside her husband's head. It’s a gut-wrenching way to put it, but medically, it’s fairly accurate.

Did Robin Williams have Lewy Body? Yes. And by the time he passed, it was one of the worst cases doctors had ever seen. Neurologists who reviewed his records after the fact noted that there wasn't a single area of his brain that wasn't riddled with these toxic protein clumps.

Imagine your brain’s wiring is a massive switchboard. Now imagine someone comes in and starts pouring thick, sticky sludge over the circuits. That’s Lewy Body. It’s a condition where abnormal deposits of a protein called alpha-synuclein build up in the brain. These "Lewy bodies" mess with your dopamine (which controls movement) and your acetylcholine (which handles memory and learning).

It’s like having Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s at the same time, with a side of vivid hallucinations.

✨ Don't miss: Jada Adriana Olivarez: Why the Viral Buzz and Leaks Are a Reality Check

A Timeline of Confusion

Robin’s final year was a chaotic mess of symptoms that didn't seem to belong together. Honestly, the doctors were stumped. He was chasing ghosts.

- October 2013: It started with "gut discomfort," constipation, and heartburn. Weird, right? You wouldn't think a brain disease starts in the stomach, but LBD often hits the enteric nervous system first.

- Winter 2013: Paranoia set in. He was looping—getting stuck on the same thought over and over. He couldn't sleep. He’d thrash around in bed so much he had to sleep in a separate room.

- May 2014: He was misdiagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. While he did have the "Parkinsonian mask" (a frozen facial expression) and a slight tremor, the diagnosis didn't explain the crushing anxiety.

- The Final Months: His "cognitive reserve"—the sheer power of his genius—had kept him afloat for a while. But eventually, the dam broke. He couldn't remember his lines while filming Night at the Museum 3. This was a man who had just finished a Broadway run with hundreds of lines, and suddenly he couldn't hold onto a single sentence.

Why Nobody Knew

One of the most tragic things about LBD is how hard it is to pin down. It’s the "great mimicker." It looks like depression. It looks like standard Parkinson’s. It looks like Alzheimer’s.

In Robin’s case, he had a history of depression. When he started showing signs of it again, doctors assumed it was just a relapse. They didn't realize his brain was physically disintegrating.

What’s even crazier? He never told anyone he was hallucinating. Doctors later suspected he was seeing things—common in LBD—but he was likely too terrified to admit it. He thought he was losing his mind. He asked his wife, "Am I schizophrenic? Do I have Alzheimer's?"

The answers he got were "No," because he didn't fit those boxes perfectly. He was stuck in a medical no-man's-land.

The Autopsy Findings

When the report came out, it was staggering. The pathology showed a 40% loss of dopamine neurons. His brain was essentially "covered" in Lewy bodies.

✨ Don't miss: The Real Story of Yvonne De Carlo in 2006: A Screen Icon’s Quiet Final Chapter

Dr. Bruce Miller, a director of Memory and Aging at UCSF, told Susan that Robin’s case was exceptionally aggressive. Most people with this level of brain damage can't walk or talk. The fact that Robin was still functioning, still trying to film movies, and still riding his bike was a testament to his sheer willpower.

What We Can Learn from Robin’s Wish

There's a documentary called Robin's Wish that goes deep into this. It’s not a movie about a celebrity tragedy; it’s a movie about a neurological disaster.

If you or someone you love is dealing with a weird mix of movement issues, intense anxiety, and "brain fog" that comes and goes, you need to know about LBD. It’s not rare—about 1.4 million Americans have it—but it’s wildly underdiagnosed.

Key takeaways for those navigating similar waters:

- Look for "fluctuations." One hour the person is totally lucid; the next, they’re staring into space. That’s a hallmark of LBD.

- Check for REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. If someone is acting out their dreams (punching, kicking, yelling in their sleep), that’s often the very first sign of a Lewy Body problem, sometimes appearing years before memory loss.

- Find a Specialist. General neurologists often miss the nuances. You want a movement disorder specialist or a behavioral neurologist.

- Careful with Antipsychotics. This is huge. People with LBD are often hypersensitive to traditional antipsychotics (like Haldol). Giving these to an LBD patient can be fatal or cause permanent damage.

Robin Williams didn't "give up." He was fighting a war against a disease that was dismantling his identity piece by piece. Understanding the Lewy Body diagnosis doesn't make his death any less sad, but it does strip away the stigma. He wasn't just depressed; he was very, very sick.

If you want to support the cause or learn more, the Lewy Body Dementia Association (LBDA) is the gold standard for resources. They helped consult on Robin's story to make sure the facts were straight, and they continue to help families navigate the "terrorist" in the brain every single day.

✨ Don't miss: Dr G Medical Examiner Age: Why She Still Matters in 2026

Keep an eye out for those subtle shifts in mood and movement—sometimes the gut feeling that "something is just wrong" is the most accurate diagnostic tool we have.