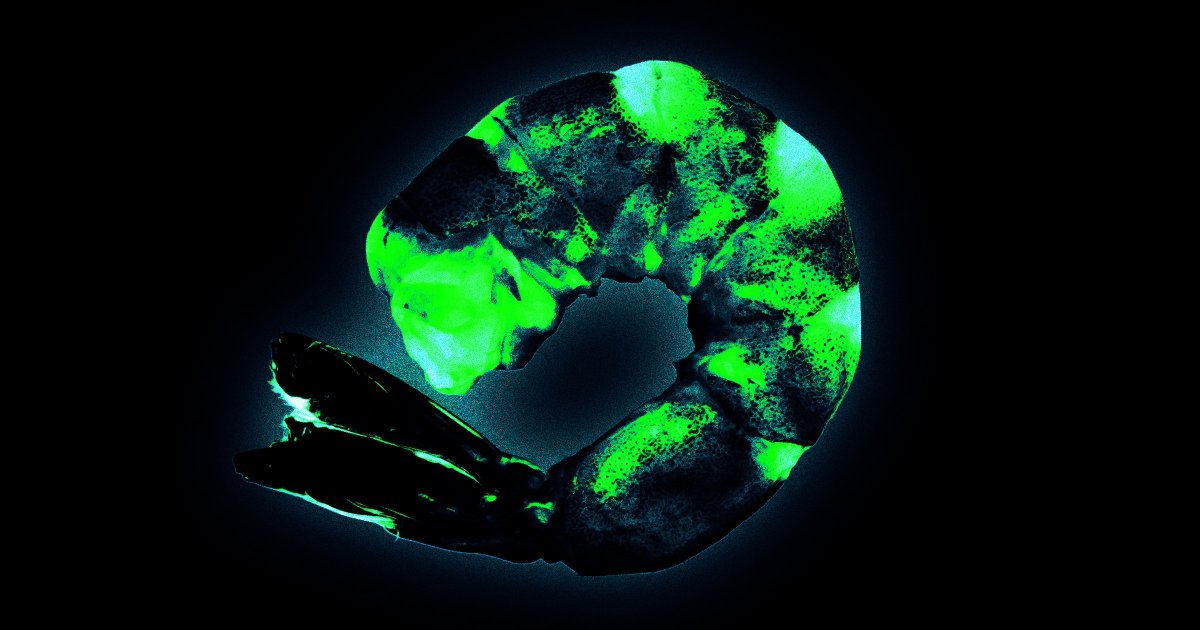

So, you’re scrolling through your feed and you see a headline that sounds like a plot from a 1950s B-movie: "Radioactive Shrimp Found." It’s a terrifying image. You probably picture a glowing, neon-green crustacean scuttling across the seafloor, ready to cause a Godzilla-sized problem. But if we’re being real, the science behind how did the shrimp become radioactive is a lot more subtle—and in some ways, a lot more concerning—than a sci-fi flick.

It isn’t just one thing. There isn't some secret underwater lab leaking glowing goo. Instead, it’s a mix of historical nuclear testing, modern industrial accidents, and the way biology actually works in the deep ocean.

The ocean is big. Really big. You’d think anything we put in it would just disappear, right? Dilution is the solution to pollution? Not exactly. When we talk about how did the shrimp become radioactive, we’re mostly talking about isotopes like Cesium-137 and Carbon-14. These aren't just floating around; they get baked into the food chain.

The Fukushima Factor and Global Currents

When the Tōhoku earthquake and subsequent tsunami hit the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in 2011, the world watched in horror. It was a mess. Massive amounts of cooling water, contaminated with radionuclides, flowed directly into the Pacific.

This is usually the first thing people point to when asking how did the shrimp become radioactive. Scientists, like those from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, have been tracking these plumes for over a decade. While the vast majority of the "hot" water diluted as it crossed the Pacific toward the California coast, the biology of the shrimp changed the math.

Shrimp are bottom feeders. They are the janitors of the sea. They spend their lives sifting through marine snow—which is a polite way of saying they eat the decaying bits of fish, poop, and algae that sink to the bottom. If a radioactive isotope hitches a ride on a piece of organic matter, the shrimp eats it.

The radioactive particles don't just pass through. They bioaccumulate.

Why Deep-Sea Shrimp Are Different

In 2019, a study published in Geophysical Research Letters blew some minds. Researchers looked at amphipods—tiny, shrimp-like creatures—in the deepest parts of the ocean, specifically the Mariana Trench. They found elevated levels of Carbon-14 in their muscle tissues.

How? That's the real kicker.

📖 Related: What Really Happened With Trump Revoking Mayorkas Secret Service Protection

This wasn't from Fukushima. This was a "gift" from the Cold War. During the 1950s and 60s, the US and the USSR were detonating nuclear bombs in the atmosphere like it was going out of style. These "bomb-pulse" isotopes eventually settled into the ocean. Surface organisms took them up, died, and sank. The shrimp at the bottom of the world’s deepest trenches are essentially eating the fallout of the 20th century.

It’s a long-term lag. The surface might look clean, but the basement of the ocean is holding onto the receipts.

Honestly, it’s kinda wild to think that a shrimp 36,000 feet below the surface is radioactive because of a bomb test that happened before your parents were born. But that’s the reality of how did the shrimp become radioactive. It’s a slow-motion environmental impact.

The British Coast and the Sellafield Legacy

If we move away from the Pacific, we find another story in the Irish Sea. For decades, the Sellafield nuclear reprocessing plant in the UK discharged low-level waste into the water. We're talking about Technetium-99.

Local fishermen and researchers noticed something. The lobsters and shrimp in the area were showing much higher concentrations of these isotopes than the surrounding water. Why? Because crustaceans have a biological quirk. Their shells and tissues are remarkably good at absorbing certain minerals and metals.

If the environment has a tiny bit of Technetium, the shrimp acts like a sponge. It concentrates the material. So, while the water might be "safe" to swim in, the shrimp living in it is a concentrated capsule of whatever has been dumped.

Is it Dangerous to Eat?

This is the question everyone actually cares about. You’re at a seafood boil and you’re wondering if you’re going to start glowing.

The short answer? No.

👉 See also: Franklin D Roosevelt Civil Rights Record: Why It Is Way More Complicated Than You Think

The long answer? It’s about dosage.

Health experts and organizations like the FDA and the European Food Safety Authority have been testing Pacific seafood for years. The levels of Cesium-137 found in shrimp are usually thousands of times lower than the "limit of concern." To get a dangerous dose of radiation from these shrimp, you’d basically have to eat several tons of them in a single sitting. You’d die of a stomach explosion or mercury poisoning long before the radiation got to you.

But "safe for consumption" and "environmentally pure" are two different things.

The fact that we can even detect these isotopes shows how much we've altered the planet's chemistry. It’s a marker of the Anthropocene. We can find human-made radiation in a shrimp's belly because we've left a permanent fingerprint on the Earth.

Misconceptions About "Glowing" Seafood

Let's clear one thing up: radioactive shrimp do not glow. If you see a shrimp glowing in the dark, it’s not because of a nuclear reactor. It’s almost certainly bioluminescence or a specific type of bacteria called Vibrio fischeri.

Radiation doesn't work like the movies. It’s invisible. It’s quiet. It’s measured in Becquerels, not in light bulbs. When people ask how did the shrimp become radioactive, they are often looking for a dramatic event, but it’s usually just the boring, steady accumulation of particles from a century of industrial activity.

Tracking the Move: From Water to Tissue

When an isotope like Cesium enters the water, it behaves a lot like potassium. Shrimp need potassium to live. Their cells can't always tell the difference. So, the shrimp’s body pulls in the radioactive Cesium, thinking it’s a necessary nutrient.

This is called "molecular mimicry." It's a bit of a biological trick that ends up poisoning the organism from the inside out.

✨ Don't miss: 39 Carl St and Kevin Lau: What Actually Happened at the Cole Valley Property

The Real Sources of Contamination

- Atmospheric Fallout: Particles from mid-century bomb tests that are still settling into the deep sea.

- Industrial Discharge: Legal and illegal dumping from power plants and medical facilities.

- Accidental Leaks: High-profile events like Fukushima or Chernobyl (which affected the Black Sea).

- Natural Background: We forget that the earth is naturally radioactive. Uranium and Potassium-40 have always been in the ocean.

The Future of Our Seafood

We are getting better at monitoring this. The network of sensors across the world’s oceans is more sophisticated than ever. But as we decommission older nuclear plants and deal with the rising sea levels threatening coastal storage sites, the question of how did the shrimp become radioactive will stay relevant.

We have to look at the whole ecosystem. Shrimp are a "sentinel species." Because they are so sensitive to their environment and sit at the base of the food chain, they tell us exactly how healthy—or unhealthy—the ocean is. If the shrimp are showing high levels of isotopes, it’s a warning light for the entire planet.

Actionable Insights for the Concerned Consumer

If you're worried about the quality of your seafood, there are a few practical things you can do that actually matter more than worrying about "glow-in-the-dark" shrimp.

First, check the source. Seafood from the North Atlantic and parts of the Pacific is monitored strictly. Look for labels like MSC (Marine Stewardship Council) which, while not specifically a "radiation" check, ensures better oversight of the fishery's environment.

Second, diversify your diet. Bioaccumulation is worst in "top predators" like tuna or shark. Shrimp have a short lifespan. They don't have decades to soak up toxins like a large fish does. Usually, younger, smaller organisms have lower concentrations of contaminants.

Third, stay informed through scientific sources. Don't rely on viral Facebook posts or TikTok "fear-porn." Websites like the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) provide real-time data on ocean monitoring that is based on peer-reviewed science, not clicks.

Finally, support policies that protect our oceans. The real story isn't just about one radioactive shrimp; it's about the systemic way we treat the sea as a trash can. Reducing industrial runoff and supporting clean energy transition reduces the risk of future "Fukushima-style" events.

The shrimp didn't choose to be radioactive. They’re just living in the world we built for them. Understanding the science helps us move past the fear and toward better management of the waters that feed us.